Candida Martinelli's Italophile Site

Main

Page This family-friendly site celebrates Italian culture for the enjoyment of children and

adults. Site-Overview

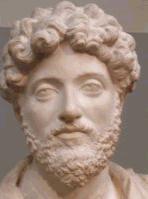

Marcus Aurelius, showing his famously gentle

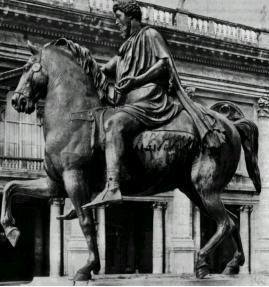

expression. Statue of Marcus Aurelius. A statue of Marcus Aurelius . Temple of Antoninus and Faustina,

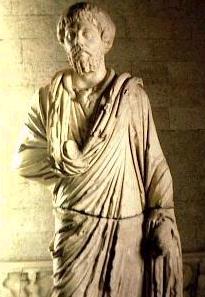

Marcus Aurelius's adoptive parents. Bust of Antoninus Pius, Marcus Aurelius's adoptive

father, and the Emperor before him. Click on the image to visit a

listing of Emperors with images of each and some basic facts about their

rule. Antonina’s

Column in Rome's 'Piazza Colonna' commemorates Marcus Aurelius's wars against the northern tribes. A close-up of the 'Colonna Antonina'. The whole 'Colonna Antonina'. A bust of Commodus, Marcus Aurelius's son, and the

head of a statue he had made of himself as a Greek God, of whom he fancied

himself to be the reincarnation. He was insane with vainglory and

self-indulgence. Click on the above logo to link to a site about the

Catacombs of Rome, to prepare for a visit, or to read about the history

of the persecution of the Early Christians under Roman rule. Click on the above logo to go to an online copy of

the 'Meditations'. It is a different translation than quoted on

this page. Click on the above text to go to yet another

translation and online copy of the 'Meditations'. Click on the above text to go to another online

copy of the same translation as the previous one.

A bust of Marcus Aurelius. Click on the text above to read about the five good

emperors, of which Marcus Aurelius was the last. Click on the logo above to visit a list of all

Roman Emperors, linking through to biographies of each. Free e-book versions are available from Project

Gutenberg, the grand-daddy of all free e-book websites.

Direct

link to the free e-books The Roman

Empire After Marcus Aurelius Limitations of Self-reflection for

Improvement Books

by or About Marcus Aurelius Marcus

Aurelius is the fifth of the so-called “five good emperors” that

preceded the decline of the Roman Empire.

He was hand picked, carefully educated, and trained for his

position. He studied at the

right hand of his predecessor, Antoninus Pius, a follower of the

Stoicists, a philosophical group that advocated moderation and

self-control. The Stoicists believed in much that the Christians

believed, but without the rejection of the multi-god beliefs.

So it is no surprise that Marcus Aurelius knew how to perform his job and carried

out his duties with diligence, which he did from 161 to 180 A.D. He was a

man who was blessed, or cursed, depending on your point of view, with a

self-reflective nature. And

like self-reflective people, he strove to become a better person.

He recorded his self-reflective journey on paper in his personal

diary, his Meditations, which were published after his death with

the title To Himself, an ironic title considering they were

written for him alone and yet published for all the world to read. While

sometimes called a treatise on the stoic life, the writings of Marcus

Aurelius are more a diary of his reflections while on campaigns to

defend fringes of the Roman Empire from invasion by enemy hordes.

Marcus Aurelius was,

unique for a reflective person,

also

a man of action when necessary, successfully defending the Empire during

his years as Emperor from 161 to 180 A.D. from revolts in the East and

enemy tribes in the North. He is also

credited with instituting other important reforms in the Empire. Laws

introduced to protect the weak from exploitation by the strong and

wealthy Laws

to protect slaves from abuse Laws

to provide for families who lost their breadwinner Foundation

of charitable institutions to help care for and educate poor

children Greater

protection for the outlying provinces against oppression Public

assistance to cities or districts struck by disasters Marcus

Aurelius and his wife, Faustina, who was also his first cousin, had

seven children all of delicate health.

Only one grew to adulthood, and he was weak not only of health

but of morality. It is

difficult to say whether the stories of Faustina’s infidelities are

true, because it is a common slander in patriarchal societies, but

Commodus was so unlike his father, that it led credence to the rumors. Marcus's

son

was wholly unsuited to be Emperor.

Alongside his ridiculously excessive vices, both sexual and in

corruption of civic life, Commodus failed to defend the Empire from

attack. He accommodated

Rome’s enemies, buying them off, thus encouraging more to try their

hand at attacking and blackmailing the vast empire. Instead of

dissuading theft-by-war with deadly resistance, he encouraged it by

making the only risk being not getting a high enough price to pay off one’s

allies. Since the gains far

outweighed the risks, the attacks continued, damaging the security of

the empire, cutting off valuable trade routes, and disrupting the time

sensitive plantings and reaping of food needed to feed the empire. Commodus,

who was killed by his own servants for the good of the empire and to

save their own lives from the fickle sadist, was followed by other

vice-filled weak leaders leading to the decline of the military, thus

leaving the Empire open to piecemeal attacks and annexations from all

sides. Other

self-reflective people have found inspiration in Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations. They should, however, also look at the book for a better

understanding of the limitations of self-reflection as a tool for

self-improvement. If the

person wishing to become a better person is closed off to external ideas

and looks only within or to those within their trusted circle, the ideas

they consider for self-criticism and self-improvement can be too limited

to make them a truly good person. This was

the case with Marcus Aurelius. He

accepted the ideas of the superstitious peoples of his time. He

condoned, and at times more than condoned, the persecution of the

minority Christians in the superstitious hope of bettering the lives of

the majority pagan citizens. Like all

superstitious peoples, the majority liked to blame all misfortune on

others, rather than just accept that misfortunes happen sometimes for no

reason whatsoever. The idea

of a chaotic and at times deadly universe was too frightening to

consider. And the idea that

these misfortunes were the result of failed leadership was something the

authorities did not want to encourage. The

majority looked to what was different around them for the reasons for

their suffering, or for the excuse.

What was very obviously different in those first centuries after

Christ’s death, was the growth of the one-God Christian faith that

disapproved of the institutionally sadistic society around them.

This radical shift from the multi-god religions and pantheism was

“blasphemy” of the most basic kind. The

majority’s pagan religion offered lots of gods to be bribed to look

after all aspects of their lives. So

when they wanted to control the chaos, they knew where to turn and what

to do. Sacrifices of money,

food, and life, not their own, were the currency of security. If the

payment didn’t work, they never wasted time wondering if they were

wrong, they just concluded they hadn’t paid a high enough price.

So they upped the amount paid, until it did work, which meant

more Christians had to die. During

this period in Rome’s history, there were many natural disasters such

as earthquakes, floods, pestilence, and starvation.

There were also enemy invasions and revolts by allies.

With each event, the payments to the gods were

increased, until

thousands of Christians were being killed in attempts to appease the

voracious gods. Marcus

Aurelius’s complicity with this mass-murder shows that self-reflection

without enlightened thought can get a person only so far.

It would take the Enlightenment and it’s descendent, Liberal

Humanism, to bring humanity to a higher moral level. While, to

me, much of the Meditations reads as a drunken or drug induced

rant by a tired and life-weary man, they have their moments of interest.

An interesting note: they

were written in Greek, the language of the educated at the time. Only much later did Latin take up that role, usurped

eventually by English, as attested to by the scientific and academic

journal preference for English. Some

points, key to the Stoic Philosophy, are repeated throughout the twelve

Books that make up the Meditations. Reason

must rule the body; logic must be used to determine the truth, by

first collecting differing ideas and then testing them against the

facts to see which hold firm, and re-evaluating them as new facts

become available. Live

according to nature, which means accepting that we are all a part of

God’s universe with a bit of God in all of us, called our soul,

and we must try to behave as God-like as possible to honor our soul

and God, and the most God-like behavior is to work for the common

good. It is

in your own power to maintain the beauty of your soul, or to be a

decent human being; the ethics of our lives, how we put to use the

truths we determine, define who we are and we are in control of our

choices and behavior; the highest good is a virtuous life and that

can be achieved by living in moderation. Death

can come at any moment so be prepared for it; this is a common

sentiment in those faraway times (and sadly for many still today)

with poor healthcare, irregular diets, poor storage and preservation

of food, and frequent violence; Marcus Aurelius certainly thought of

it more than others because he suffered poor health all his life,

dying at the age of 59 from a long and painful illness. Use

self-reflection to purify your soul and find truth and right; review

each day your actions and reactions to others and ask yourself if

you behaved as you should, then resolve to improve your behavior the

next day; also keep good thoughts, as thoughts predetermine our

actions. Fame

is fleeting so one should not seek it, and if one has it, don’t

court it or indulge in it, or place too high a value on it, because

it has so little real value in the big scheme of things; as Emperor,

one can imagine his position gained him many wannabe sycophants, and

it seems clear that Marcus Aurelius shunned them; he is famous for

appointing worthy advisers and military and civic leaders. My list of books by or about Marcus Aurelius available at

Amazon.com

To broaden your search to the era or contemporaries,

you can use this Search tool for Amazon.com.

Just

enter 'Books' in the 'Search' field, and names or words in the

'Keyword' field (for example 'Antoninus Pius' or 'Commodus'). Then click on the 'Go' button to see what's

available, what people's comments about the books are, and what they

cost.

Here

are some passages from the Meditations by Marcus Aurelius, that I

found interesting, that I thought you might enjoy. Book

One, VIII: …how

much envy and fraud and hypocrisy the state of a tyrannous king is

subject unto, and how they who are commonly called nobly born, are in

some sort incapable, or void of natural affection. Book

Two, II: Let

it be thy earnest and incessant care as a Roman and a man to perform

whatsoever it is that thou art about, with true and unfeigned gravity,

natural affection, freedom and justice… Which thou shalt do; if thou

shalt go about every action as thy last action, free from all vanity,

all passionate and wilful aberration from reason, and from all

hypocrisy, and self-love…those things, which for a man to hold on in a

prosperous course, and to live a divine life, are requisite and

necessary, are not many… Book

Two, IV: …Give thyself

leisure to learn some good thing, and cease roving and wandering to and

fro… Book

Two, V: …whosoever they

be that intend not, and guide not by reason and discretion the motions

of their own souls, they must of necessity be unhappy. Book

Two, VII: …those sins are

greater which are committed through lust, than those which are committed

through anger. For he that is angry seems with a kind of grief and close

contraction of himself, to turn away from reason; but he that sins

through lust, being overcome by pleasure, doth in his very sin betray a

more impotent, and unmanlike disposition… Book

Two, VIII: Whatsoever thou

dost affect, whatsoever thou dost project, so do, and so project all, as

one who, for aught thou knowest, may at this very present depart out of

this life…and as for those things which be truly evil, as vice and.

wickedness, such things they have put in a man’s own power, that he

might avoid them if he would… Book

Two, XI: …There is

nothing more wretched than that soul, which in a kind of circuit

compasseth all things, searching (as he saith) even the very depths of

the earth; and by all signs and conjectures prying into the very

thoughts of other men's souls; and yet of this, is not sensible, that it

is sufficient for a man to apply himself wholly, and to confine all his

thoughts and cares to the tendance of that spirit which is within him,

and truly and really to serve him. His service doth consist in this,

that a man keep himself pure from all violent passion and evil

affection, from all rashness and vanity, and from all manner of

discontent… Book

Two, XV: The time of a

man's life is as a point; the substance of it ever flowing, the sense

obscure; and the whole composition of the body tending to corruption.

His soul is restless, fortune uncertain, and fame doubtful; to be brief,

as a stream so are all things belonging to the body; as a dream, or as a

smoke, so are all that belong unto the soul.

Our life is a warfare, and a mere pilgrimage. Fame after life is

no better than oblivion. What

is it then that will adhere and follow?

Only one thing, philosophy. And philosophy doth consist in this,

for a man to preserve that spirit which is within him, from all manner

of contumelies and injuries, and above all pains or pleasures; never to

do anything either rashly, or feignedly, or hypocritically: wholly to

depend from himself and his own proper actions: all things that happen

unto him to embrace contentedly, as coming from Him from whom he himself

also came; and above all things, with all meekness and a calm

cheerfulness, to expect death, as being nothing else but the resolution

of those elements, of which every creature is composed… Book

Three, IV: …think only of

such things, of which if a man upon a sudden should ask thee, what it is

that thou art now thinking, thou mayest answer This, and That, freely

and boldly, that so by thy thoughts it may presently appear that in all

thee is sincere, and peaceable; as becometh one that is made for

society, and regards not pleasures, nor gives way to any voluptuous

imaginations at all: free from all contentiousness, envy, and suspicion,

and from whatsoever else thou wouldest blush to confess thy thoughts

were set upon… Book

Three, VIII: Never esteem

of anything as profitable, which shall ever constrain thee either to

break thy faith, or to lose thy modesty; to hate any man, to suspect, to

curse, to dissemble, to lust after anything, that requireth the secret

of walls or veils… Book

Three, X: …The time

therefore that any man doth live, is but a little, and the place where

he liveth, is but a very little corner of the earth, and the greatest

fame that can remain of a man after his death, even that is but little,

and that too, such as it is whilst it is, is by the succession of silly

mortal men preserved, who likewise shall shortly die, and even whiles

they live know not what in very deed they themselves are: and much less

can know one, who long before is dead and gone. Book

Four, III: …A man cannot

any whither retire better than to his own soul; he especially who is

beforehand provided of such things within, which whensoever he doth

withdraw himself to look in, may presently afford unto him perfect ease

and tranquillity. By

tranquillity I understand a decent orderly disposition and carriage,

free from all confusion and tumultuousness.

Afford then thyself this retiring continually, and thereby

refresh and renew thyself… Book

Four, X: …if any man that

is present shall be able to rectify thee or to turn thee from some

erroneous persuasion, that thou be always ready to change thy mind, and

this change to proceed, not from any respect of any pleasure or credit

thereon depending, but always from some probable apparent ground of

justice, or of some public good thereby to be furthered; or from some

other such inducement. Book

Four, XX: …For since it

is so, that most of those things, which we either speak or do, are

unnecessary; if a man shall cut them off, it must needs follow that he

shall thereby gain much leisure, and save much trouble, and therefore at

every action a man must privately by way of admonition suggest unto

himself, What? may not this that now I go about, be of the number of

unnecessary actions?… Book

Four, XXI: …To comprehend

all in a few words, our life is short; we must endeavour to gain the

present time with best discretion and justice.

Use recreation with sobriety. Book

Four, XXIV: He is a true

fugitive, that flies from reason, by which men are sociable.

He blind, who cannot see with the eyes of his understanding.

He poor, that stands in need of another, and hath not in himself

all things needful for this life… Book

Four, XXVII: …thy

carriage in every business must be according to the worth and due

proportion of it, for so shalt thou not easily be tired out and vexed,

if thou shalt not dwell upon small matters longer than is fitting. Book

Four, XXVIII: …And this I

say of them, who once shined as the wonders of their ages, for as for

the rest, no sooner are they expired, than with them all their fame and

memory. And what is it then

that shall always be remembered? all is vanity.

What is it that we must bestow our care and diligence upon? even

upon this only: that our minds and wills be just; that our actions be

charitable; that our speech be never deceitful, or that our

understanding be not subject to error… Book

Four, XL: Thou must be like

a promontory of the sea, against which though the waves beat

continually, yet it both itself stands, and about it are those swelling

waves stilled and quieted. Book

Five, III: …If it be

right and honest to be spoken or done, undervalue not thyself so much,

as to be discouraged from it… Book

Six, XIV: Some things

hasten to be, and others to he no more.

And even whatsoever now is, some part thereof bath already

perished. Perpetual fluxes

and alterations renew the world, as the perpetual course of time doth

make the age of the world (of itself infinite) to appear always fresh

and new… Book

Six, XX: If anybody shall

reprove me, and shall make it apparent unto me, that in any either

opinion or action of mine I do err, I will most gladly retract.

For it is the truth that I seek after, by which I am sure that

never any man was hurt; and as sure, that he is hurt that continueth in

any error, or ignorance whatsoever. Book

Six, XXVI: Death is a

cessation from the impression of the senses, the tyranny of the

passions, the errors of the mind, and the servitude of the body. Book

Six, XXVII: If in this kind

of life thy body be able to hold out, it is a shame that thy soul should

faint first, and give over, take heed, lest of a philosopher thou become

a mere Caesar in time, and receive a new tincture from the court.

For it may happen if thou dost not take heed. Keep thyself therefore, truly simple, good, sincere, grave,

free from all ostentation, a lover of that which is just, religious,

kind, tender-hearted, strong and vigorous to undergo anything that

becomes thee… Book

Six, XXVIII: (Editor: an

ode to his predecessor and adoptive father.)

Do all things as becometh the disciple of Antoninus Pius.

Remember his resolute constancy in things that were done by him

according to reason, his equability in all things, his sanctity; the

cheerfulness of his countenance, his sweetness, and how free he was from

all vainglory; how careful to come to the true and exact knowledge of

matters in hand, and how he would by no means give over till he did

fully, and plainly understand the whole state of the business; and how

patiently, and without any contestation he would bear with them, that

did unjustly condemn him: how he would never be over-hasty in anything,

nor give ear to slanders and false accusations, but examine and observe

with best diligence the several actions and dispositions of men.

Again, how he was no backbiter, nor easily frightened, nor

suspicious, and in his language free from all affectation and curiosity:

and how easily he would content himself with few things, as lodging,

bedding, clothing, and ordinary nourishment, and attendance.

How able to endure labour, how patient; able through his spare

diet to continue from morning to evening without any necessity of

withdrawing before his accustomed hours to the necessities of nature:

his uniformity and constancy in matter of friendship.

How he would bear with them that with all boldness and liberty

opposed his opinions; and even rejoice if any man could better advise

him: and lastly, how religious he was without superstition.

All these things of him remember, that whensoever thy last hour

shall come upon thee, it may find thee, as it did him, ready for it in

the possession of a good conscience. Book

Six, XLVIII: Use thyself

when any man speaks unto thee, so to hearken unto him, as that in the

interim thou give not way to any other thoughts; that so thou mayst (as

far as is possible) seem fixed and fastened to his very soul, whosoever

he be that speaks unto thee. Book

Six, XLIX: That which is

not good for the bee-hive, cannot be good for the bee. Book

Seven, XV: Is any man so

foolish as to fear change, to which all things that once were not owe

their being?… Book

Seven, XXXIII: The art of

true living in this world is more like a wrestler's, than a dancer's

practice. For in this they

both agree, to teach a man whatsoever falls upon him, that he may be

ready for it, and that nothing may cast him down. Book

Seven, XXXVIII: For it is a

thing very possible, that a man should be a very divine man, and yet be

altogether unknown. This

thou must ever be mindful of, as of this also, that a man's true

happiness doth consist in very few things… Book

Seven, XL: Then hath a man

attained to the estate of perfection in his life and conversation, when

he so spends every day, as if it were his last day:

never hot and vehement in his affections, nor yet so cold and

stupid as one that had no sense; and free from all manner of

dissimulation. Book

Eight, II: Upon every

action that thou art about, put this question to thyself; How will this

when it is done agree with me? Shall I have no occasion to repent of

it?… Book

Eight, VIII: Forbear

henceforth to complain of the trouble of a courtly life, either in

public before others, or in private by thyself. Book

Eight, XIII: At thy first

encounter with any one, say presently to thyself: This man, what are his

opinions concerning that which is good or evil? as concerning pain,

pleasure, and the causes of both; concerning honour, and dishonour,

concerning life and death? thus and thus.

Now if it be no wonder that a man should have such and such

opinions, how can it be a wonder that he should do such and such

things?… Book

Eight, XIV: Remember, that

to change thy mind upon occasion, and to follow him that is able to

rectify thee, is equally ingenuous, as to find out at the first, what is

right and just, without help. For

of thee nothing is required, that is beyond the extent of thine own

deliberation and judgment, and of thine own understanding. Book

Eight, XXVIII: Whether thou

speak in the Senate or whether thou speak to any particular, let thy

speech In always grave and modest…. Book

Eight, XLIX: Not to be

slack and negligent; or loose, and wanton in thy actions; nor

contentious, and troublesome in thy conversation; nor to rove and wander

in thy fancies and imaginations. Not

basely to contract thy soul; nor boisterously to sally out with it, or

furiously to launch out as it were, nor ever to want employment. Book

Eight, LI: He that knoweth

not what the world is, knoweth not where he himself is. Book

Eight, LVI: All men are

made one for another: either then teach them better, or bear with them. Book

Eight, LVII: The motion of

the mind is not as the motion of a dart.

For the mind when it is wary and cautelous, and by way of

diligent circumspection turneth herself many ways, may then as well be

said to go straight on to the object, as when it useth no such

circumspection. Book

Nine, I: He that is unjust,

is also impious. For the

nature of the universe, having made all reasonable creatures one for

another, to the end that they should do one another good; more or less

according to the several persons and occasions but in nowise hurt one

another: it is manifest

that he that doth transgress against this her will, is guilty of impiety

towards the most ancient and venerable of all the deities… Book

Nine, II: It were indeed

more happy and comfortable, for a man to depart out of this world,

having lived all his life long clear from all falsehood, dissimulation,

voluptuousness, and pride. But

if this cannot be, yet it is some comfort for a man joyfully to depart

as weary, and out of love with those; rather than to desire to live, and

to continue long in those wicked courses… Book

Nine, IX: Either teach them

better if it be in thy power; or if it be not, remember that for this

use, to bear with them patiently, was mildness and goodness granted unto

thee… Book

Nine, XIV: As virtue and

wickedness consist not in passion, but in action; so neither doth the

true good or evil of a reasonable charitable man consist in passion, but

in operation and action. Book

Nine, XVI: Sift their minds

and understandings, and behold what men they be, whom thou dost stand in

fear of what they shall judge of thee, what they themselves judge of

themselves. Book

Nine, XVIII: It is not

thine, but another man's sin. Why

should it trouble thee? Let

him look to it, whose sin it is. Book

Nine, XXV: When any shall

either impeach thee with false accusations, or hatefully reproach thee,

or shall use any such carriage towards thee, get thee presently to their

minds and understandings, and look in them, and behold what manner of

men they be… Book

Nine, XXVI: Up and down,

from one age to another, go the ordinary things of the world; being

still the same… Book

Nine, XXVIII: And these

your professed politicians, the only true practical philosophers of the

world, (as they think of themselves) so full of affected gravity, or

such professed lovers of virtue and honesty, what wretches be they in

very deed; how vile and contemptible in themselves?… Book

Nine, XXXV: Will this

querulousness, this murmuring, this complaining and dissembling never be

at an end?… Book

Nine, XLIII: When at any

time thou art offended with any one's impudency, put presently this

question to thyself: 'What?

Is it then possible, that there should not be any impudent men in

the world! Certainly it is not possible.'… Book

Ten, IX: Toys and fooleries

at home, wars abroad: sometimes

terror, sometimes torpor, or stupid sloth: this is thy daily slavery… Book

Ten, XVII: So live as

indifferent to the world and all worldly objects, as one who liveth by

himself alone upon some desert hill… Book

Eleven, III: That soul

which is ever ready, even now presently (if need be) from the body,

whether by way of extinction, or dispersion, or continuation in another

place and estate to be separated, how blessed and happy is it!… Book

Eleven, XIV: How rotten and

insincere is he, that saith, I am resolved to carry myself hereafter

towards you with all ingenuity and simplicity.

O man, what doest thou mean! what needs this profession of thine? The thing itself will show it.

It ought to be written upon thy forehead. No sooner thy voice is heard, than thy countenance must be

able to show what is in thy mind: even

as he that is loved knows presently by the looks of his sweetheart what

is in her mind… Book

Eleven, XXI: Socrates was

wont to call the common conceits and opinions of men, the common

bugbears of the world: the

proper terror of silly children. Book

Twelve, II: God beholds our

minds and understandings, bare and naked from these material vessels,

and outsides, and all earthly dross… Book

Twelve, III: I have often

wondered how it should come to pass, that every man loving himself best,

should more regard other men's opinions concerning himself than his

own… Book

Twelve, X: How ridiculous

and strange is he, that wonders at anything that happens in this life in

the ordinary course of nature! Book

Twelve, XIII: If it be not

fitting, do it not. If it

be not true, speak it not. Ever

maintain thine own purpose and resolution free from all compulsion and

necessity. Book

Twelve, XXV: What a small

portion of vast and infinite eternity it is, that is allowed unto every

one of us, and how soon it vanisheth into the general age of the world: of the common substance, and of the common soul also what a

small portion is allotted unto us:

and in what a little clod of the whole earth (as it were) it is

that thou doest crawl. After

thou shalt rightly have considered these things with thyself; fancy not

anything else in the world any more to be of any weight and moment but

this, to do that only which thine own nature doth require; and to

conform thyself to that which the common nature doth afford. References: Various including those referenced on this page, and Marcus

Aurelius’s Meditations, Penguin Popular Classics edition, and

the Project Gutenberg free text file with the same translation.

Also see my pages:

The

Diary of Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius - Meditations to Himself--Excerpts

and links

to full text

![]()

The Roman

Empire After Marcus Aurelius

The

Limitations of Self-reflection for Self-improvement

The Meditations

Books

by or About Marcus Aurelius

Excerpts

from the Meditations