Candida Martinelli's Italophile Site

Main

Page This family-friendly site celebrates Italian culture for the enjoyment of children and

adults. Site-Overview

Quick Link:

Quotes Below

Click on a chapter title to access that chapter to read

on-line from this site. Table of Contents Chapter 1 - It began in a Woman's Club Chapter 4 - It had been arranged Chapter 5 - It was cloudy in Italy Chapter 6 - When Mrs. Wilkins woke next morning Chapter 7 - Their eyes followed her admiringly Chapter 9 - That one of the two sitting-rooms Chapter 10 - There was no way of getting into or out of the top

garden Chapter 11 - The sweet smells that were everywhere Chapter 12 - At the evening meal Chapter 13 - The uneventful days Chapter 14 - That first week the wisteria began to fade Chapter 15 - The strange effect of this incidence Chapter 16 - And so the second week began Chapter 17 - On the first day of the third week Chapter 18 - They had a very pleasant walk Chapter 19 - And then when she spoke Chapter 20 - Scrap wanted to know so much about her mother Chapter 21 - Now Frederick was not the man to hurt anything Chapter 22 - That evening was the evening of the full moon

You

can download the book for free, as a PDF document to be read with the

Adobe

Reader.

Click on this link to open the book I've created:

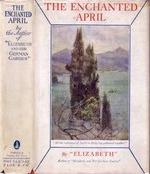

The Enchanted April

My version

of the novella is a copy I've edited (removing scanning and editing

errors only), from

Project Gutenberg. You can

download the book from

them in various formats, also for free. An image of a younger Elizabeth. You can view the film "Enchanted April" via YouTube. Here is the first part.

I suggest if you like what you see, you should purchase the DVD for the beautiful,

full-sized images of the luscious gardens, views and castle.

The 1992 film was filled on location in Portofino, Italy,

at Castello Brown, the castle where Elizabeth von Arnim stayed in 1920,

and where she is said to have written the novella The Enchanted April. It is a museum

today, owned by the city of Portofino, and open to the public.

Portofino's Castello Brown

Castello Brown

I have Elizabeth's Garden and Solitary

Summer on my site.

And the online Project Gutenberg has more

von Arnim books you can read online, such as My Italian Garden

page

Novelist Elizabeth von Arnim (b.1866-d.1941)

Elizabeth von Arnim was born in 1866 and died in 1941. She was

Australian by birth, English by upbringing, German and English by marriages,

Swiss and French by choice, and in the end,

American by emigration. She was the cousin of New Zealander-English short-story writer Katherine

Mansfield, who lived as an adopted sister with her family for many years.

Short-story writer Katherine Mansfield, Elizabeth's

cousin While living in Germany in 1904, Elizabeth hired

E. M. Forster to tutor

her children. Interestingly, E. M. Forster authored the novella A Room with a View

(1908). And one event from Elizabeth's life seems to appear

in disguise in Forster's novella: Elizabeth met her husband while in Italy, touring with her father,

when her husband first took notice of Elizabeth as she was playing an

organ

piece by Bach in a church in Rome. Elizabeth was an inspiration for

Forster,

and he admitted that he based at least one of his books' characters on

her. Elizabeth published

21 books during her lifetime, and wrote at least one play, that was

produced to great success, based on her novel Princess Priscilla's

Fortnight.

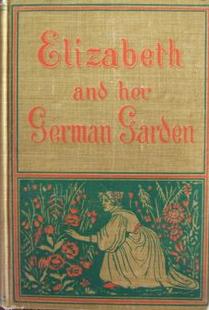

Elizabeth and her German Garden published in 1898,

was Elizabeth's most popular book, and it is,

like all her books,

still

highly entertaining to today's readers. It

is ostensibly the diary of a woman who is creating a garden, but

it is really a novel about

her unusual views on life, on German and English society, and her on friends.

The book was so popular, reprinted 20 times in the

first year of publication alone, that her later books were published

with the author identified only as "By the author of Elizabeth and her German

Garden". Only one book, an epistolary novel

purportedly by a young English girl living

in pre-WWI Germany to her mother, was published with a pseudonym, Alice Cholmondeley.

Presumably this was because the subject matter was more politically

condemning of German society than in her other novels. Thanks to

Project Gutenberg,

you can

read Elizabeth and her German Garden on-line, or download the book for free

in various formats. The companion book, published a year later, in

1899, was The Solitary Summer. I have both these books on my site.

They are lovely reads and an inspiration for gardeners. The

magical spell the garden casts over the characters in The Enchanted

April is mirrored in the spell the German garden casts over

Elizabeth. Elizabeth was a writer with a light touch, similar

in tone to E. M. Forster's lighter novels. I have most of

her novels. The style could easily be called "Jane Austen light". If you enjoy Jane

Austen's books, you will almost certainly enjoy Elizabeth's books. Elizabeth's books, if read collectively, are a

wonderful guide for young women, to prepare them for, or warn them of,

the various types of men by whom they may be wooed. For

example: There is

the Aspergers man who looks on his wife as an object rather than a human

being (The Pastor's Wife). And the sadistic bully who

crushes the life out of his woman (Vera). The philanderer

husband (In the Mountains, The Enchanted April). The

kind-hearted partner (The Benefactress, Princess Priscilla's

Fortnight). The authoritarian (Elizabeth and her German

Garden, The Solitary Summer). The wavering man who

doesn't know his own mind or heart (Fräulein Schmidt and Mr

Anstruther). The nurturing man who is romantically-sexually stunted (Christopher

and Columbus). The central female characters of many of her novels are

witty women with unusual outlooks on life. Elizabeth was just such

a woman. A woman whose nephew called "my eccentric aunt".

A woman who entertained her friends by reading sections from her diary

aloud. A woman who could dazzle with her wit and charm.

There are also plenty of naive, natural, odd-ball women, that one wants

to shake out of their cloud world.

After her husband, the Count von Arnim, passed

away, Elizabeth built a home in Switzerland, in the mountains near

Valois, for herself and her children. She had lost her English

citizenship when she married the Count. At the outbreak of WWI,

she fled with her children to England, minus one daughter who was

married to a German man and living in Germany. Her second husband,

a prominent English nobleman, probably helped her regain English

citizenship for herself and her children. But that marriage was doomed from the

start because the couple's characters were so unsuited to each other. After WWI, Elizabeth spent time in the U.S. (her

second daughter married an American), London (her other children eventually

settled in England), and the south of France, at her villa "Le Mas des Roses" at Mougins, outside Cannes. It was WWII that

finally sent Elizabeth to live in the States, and that is where she

passed away in 1941. The film adaptation of

the novella The Enchanted April was made for British TV in 1991, directed by Mike Newell, and was released in theaters in 1992. It was nominated for several awards and

won many of them. It was then adapted to stage.

The Enchanted April is the story of a woman, worn down by her

demanding, cold husband and by her daily routine, who escapes to a rented

castle in Italy with an equally worn down girlfriend. They share

the castle and gardens with two other women, both, also, suffering from a lack

of love. By the end of their fairytale-like month's

vacation, all are engulfed in love of one sort or another. This was not the first time The Enchanted April

was adapted to another form. It was made into a play that was then

the basis of a film in 1935, starring Ann Harding and Frank Morgan as

Mr. and Mrs. Arbuthnot.

Ann Harding and Frank

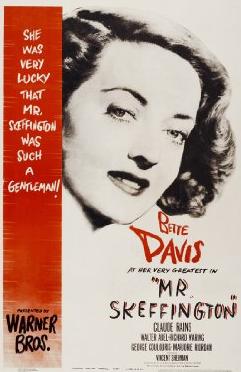

Morgan as Mr. and Mrs. Arbuthnot Elizabeth's novel Mr. Skeffington,

published in 1940, was also adapted to film, in 1944, and starred Bette

Davis. The main character is a vain woman who seems only to love

herself and her brother. It is only when she loses her looks late

in life, that she finds happiness in caring for her blind brother.

His blindness, and his memories of her beauty, allow her live as the

beauty she once was, if only in her brother's blind eyes.

If something about that rings a bell,

you have probably seen the 1992 film "Enchanted April". The

film departs from the novella by incorporating the Mr. Skeffington

trope of a beautiful woman finding true love only when the man is not

blinded by her beauty because he is truly blind or nearly blind. The version of the novella The Enchanted April

that I use here on my site, is from

Project Gutenberg,

the free online book source for out-of-print texts. I've edited out

scanning and editing errors only, to create the version I use for you to

read on-line. The hyperlinked Table of Contents is above in the left

column, or you can go directly to the First Chapter,

or you can open it as a PDF book

you can get here from my site.

Unlike the film A Room with a View, adapted

from a novella by E. M. Forster, the latest filming of The Enchanted

April did not follow the novella practically word for word, scene

for scene. Reading the novella The Enchanted April is

much more enjoyable than the film. I highly recommend the book. If you wish to see

the film again, after reading the novella, you can see it on YouTube in

several parts. I link to the first part in the left column. I collected together some fun quotes from the

novella as I read it, and report them here below. To Those Who Appreciate Wisteria and Sunshine.

Small mediaeval Italian Castle on the shores of the Mediterranean to be

Let furnished for the month of April. Necessary servants remain. Z,

Box 1000, The Times. (Ad in The Times that starts it all, Chapter 1) Mr. Wilkins, a solicitor, encouraged thrift,

except that branch of it which got into his food. He did not call that

thrift, he called it bad housekeeping. (About Mrs. Wilkins’s exigent

husband, from whom she needs a holiday, Chapter 1) Mrs. Arbuthnot … was looking fixedly at one

portion of the first page of The Times, holding the paper quite still,

her eyes not moving. She was just staring; and her face, as usual, was

the face of a patient and disappointed Madonna. (Mrs. Arbuthnot, Mrs.

Wilkins’s ‘partner in crime’, Chapter 1) Why couldn't two unhappy people refresh each other

on their way through this dusty business of life by a little talk--real,

natural talk, about what they felt, what they would have liked, what

they still tried to hope? (Mrs. Wilkins’s reasoning on why she and Mrs.

Arbuthnot should become friends, Chapter 1) Why, it would really be being unselfish to go away

and be happy for a little, because we would come back so much nicer.

You see, after a bit everybody needs a holiday. (Mrs. Wilkins’s

unselfish wish to escape England and her husband, Chapter 1) And Frederick, from her passionately loved

bridegroom, from her worshipped young husband, had become second only to

God on her list of duties and forbearances. (Mrs. Arbuthnot’s view of

her husband, Chapter 2) She would be in Italy--a place she adored; she

would not be in hotels--places she loathed; she would not be staying

with friends--persons she disliked…. (Lady Caroline’s reason for answer

the ad to share the castle, Chapter 2) She only asked, she said, to be allowed to sit

quiet in the sun and remember. That was all Mrs. Arbuthnot and Mrs.

Wilkins asked of their sharers. It was their idea of a perfect sharer

that she should sit quiet in the sun and remember, rousing herself on

Saturday evenings sufficiently to pay her share. (And Mrs. Fisher makes

their fourth, Chapter 3) "Did you know Keats?" eagerly interrupted Mrs.

Wilkins. Mrs. Fisher, after a pause, said with sub-acid reserve that

she had been unacquainted with both Keats and Shakespeare. (Faux pas

time, yet again, for shy Mrs. Wilkins, Chapter 3) To Italy he would go; and as it would cause

comment if he did not take his wife, take her he must--besides, she

would be useful; a second person was always useful in a country whose

language one did not speak for holding things, for waiting with the

luggage. (Why Mr. Wilkins invited his wife to Italy, Chapter 4) We're brow-beaten--we're not any longer real human

beings. Real human beings aren't ever as good as we've been. (Mrs.

Wilkins’s theory on why they are not happy leaving for Italy, Chapter 4) … the rain was coming down in what seemed solid

sheets. But it was Italy. Nothing it did could be bad. The very rain

was different-- straight rain, falling properly on to one's umbrella;

not that violently blowing English stuff that got in everywhere. (Why

the ladies thought Italian rain superior to English rain, Chapter 5) He went on talking, however, while he piled the

suit-cases up round them, sure that sooner or later they must understand

him, especially as he was careful to talk very loud and illustrate

everything he said with the simplest elucidatory gestures, but they both

continued only to look at him. (Beppo the Italian driver’s theory on

cross-lingual communication, Chapter 5) How much they wished their mothers had made them

learn Italian when they were little. If only now they could have said,

"Please sit round the right way and look after the horse." They did not

even know what horse was in Italian. It was contemptible to be so

ignorant. (Why the ladies wished they had learned Italian, Chapter 5) Had she really been brought here, she and poor

Mrs. Wilkins, after so much trouble in arranging it, so much difficulty

and worry, along such devious paths of prevarication and deceit, only to

be-- (Mrs. Arbuthnot fears the worst from the Italians, Chapter 5) The two men opened their umbrellas for them and

handed them to them. From this they received a faint encouragement,

because they could not believe that if these men were wicked they would

pause to open umbrellas. (An Englishwoman’s view of Italian chivalry,

Chapter 5)

And there they were, arrived; and it was San

Salvatore; and their suit-cases were waiting for them; and they had not

been murdered. (Safe and sound at their Italian castle, Chapter 5) Mrs. Wilkins put her arm round Mrs. Arbuthnot's

neck and kissed her. "The first thing to happen in this house," she

said softly, solemnly, "shall be a kiss." "Dear Lotty," said Mrs.

Arbuthnot. "Dear Rose," said Mrs. Wilkins, her eyes brimming with

gladness. Domenico was delighted. He liked to see beautiful

ladies kiss. (San Salvatore and Domenico, the gardener extraordinaire,

Chapter 5) In bed by herself: adorable condition. She had

not been in a bed without Mellersh once now for five whole years; and

the cool roominess of it, the freedom of one's movements, the sense of

recklessness, of audacity, in giving the blankets a pull if one wanted

to, or twitching the pillows more comfortably! It was like the

discovery of an entirely new joy. (Mrs. Wilkins does not miss her

husband, Chapter 6) … her own little room, her very own to arrange

just as she pleased for this one blessed month, her room bought with her

own savings, the fruit of her careful denials, whose door she could bolt

if she wanted to, and nobody had the right to come in. (Why Mrs.

Wilkins liked her room in the castle, Chapter 6) … her small face, so much puckered at home with

effort and fear, smoothed out. All she had been and done before this

morning, all she had felt and worried about, was gone. (Italy works her

magic on Mrs. Wilkins, Chapter 6) Funny to be afraid of anybody; and especially of

one's husband, whom one saw in his more simplified moments, such as

asleep, and not breathing properly through his nose. (Mrs. Wilkins’s

idea on why it is difficult to fear one’s husband, Chapter 6) I daresay when we finally reach heaven--the one

they talk about so much--we shan't find it a bit more beautiful. (Mrs.

Wilkins’s view of Castle San Salvatore, Chapter 6) … she was having a violent reaction against

beautiful clothes and the slavery they impose on one, her experience

being that the instant one had got them they took one in hand and gave

one no peace till they had been everywhere and been seen by everybody.

You didn't take your clothes to parties; they took you. (Lady

Caroline’s view of beautiful clothes, Chapter 6) … her dream of thirty restful, silent days, lying

unmolested in the sun, getting her feathers smooth again, not being

spoken to, not waited on, not grabbed at and monopolized, but just

recovering from the fatigue, the deep and melancholy fatigue, of the too

much. (Lady Caroline’s wish for April, Chapter 6) Nature was determined that she should look and

sound angelic. She could never be disagreeable or rude without being

completely misunderstood. (Lady Caroline’s frustration with nature’s

gifts, Chapter 6) In the 'eighties, when she chiefly flourished,

husbands were taken seriously, as the only real obstacles to sin. Beds

too, if they had to be mentioned, were approached with caution; and a

decent reserve prevented them and husbands ever being spoken of in the

same breath. (Mrs. Fisher’s views on husbands and beds, Chapter 7) See how everything has been let in together--the

dandelions and the irises, the vulgar and the superior, me and Mrs.

Fisher--all welcome, all mixed up anyhow, and all so visibly happy and

enjoying ourselves. (Mrs. Wilkins’s view of the four women, Chapter 8) … his smiling good-morning was received with an

answering smile; upon which Domenico forgot his family, his wife, his

mother, his grown-up children and all his duties, and only wanted to

kiss the young lady's feet. (Domenico the Italian gardener’s reaction

to beautiful Lady Catherine, Chapter 8) No good could come out of the thinking of a

beautiful young woman. Complications could come out of it in profusion,

but no good. The thinking of the beautiful was bound to result in

hesitations, in reluctances, in unhappiness all round. (Lady Caroline’s

mother’s reason for not encouraging her daughter to think during her

first 28 years of life, Chapter 8) Hardly anything was really worth while, reflected

Mrs. Fisher, except the past. It was astonishing, it was simply

amazing, the superiority of the past to the present. (Why Mrs. Fisher

chose to live in the past, Chapter 9) Beauty! All over before you can turn round. An

affair, one might almost say, of minutes. Well, while it lasted it did

seem able to do what it liked with men. Even husbands were not immune.

(Mrs. Fisher’s reflections on beauty, and Mr. Fisher’s weaknesses,

Chapter 10) The war finished Scrap. It killed the one man she

felt safe with, whom she would have married, and it finally disgusted

her with love. Since then she had been embittered. She was struggling

as angrily in the sweet stuff of life as a wasp got caught in honey.

(Lady Caroline’s situation, Chapter 10) Mrs. Fisher had a great objection to other

people's chills. They were always the fruit of folly; and then they

were handed on to her, who had done nothing at all to deserve them.

(Mrs. Fisher’s view of colds and flu and the people who spread them,

Chapter 11) "But there are no men here," said Mrs. Wilkins,

"so how can it be improper? Have you noticed," she inquired of Mrs.

Fisher, who endeavoured to pretend she did not hear, "How difficult it

is to be improper without men?" (Mrs. Wilkins on the odd relation

between propriety and men, Chapter 12) Oh, but in a bitter wind to have nothing on and

know there never will be anything on and you going to get colder and

colder till at last you die of it--that's what it was like, living with

somebody who didn't love one. (Mrs. Wilkins being indiscrete about her

relationship with Mr. Wilkins, Chapter 12) How and where husbands slept should be known only

to their wives. Sometimes it was not known to them, and then the

marriage had less happy moments; but these moments were not talked about

either; the decencies continued to be preserved. At least, it was so in

her day. (Mrs. Fisher’s views on husbands’ sleeping arrangements,

Chapter 12) The place had an almost instantaneous influence on

her as well, and of one part of this influence she was aware: it had

made her, beginning on the very first evening, want to think, and acted

on her curiously like a conscience. (Lady Catherine learns that

conscience comes from contemplation, Chapter 13) Curious, this restlessness. Was she going to be

ill? No, she felt well; indeed, unusually well, and she went in and out

quite quickly--trotted, in fact--and without her stick. (Mrs. Fisher

notes a spring in her step, Chapter 13) He had let her slip away; he had given her up; he

no longer minded; he accepted her religion indifferently, as a settled

fact. Both it and she--Rose's mind, becoming more luminous in the clear

light of April at San Salvatore, suddenly saw the truth--bored him.

(Rose Arbuthnot sees through her husband’s eyes, Chapter 13) And perhaps one's baby never did find one out;

perhaps one would always be to it, however old and bearded it grew,

somebody special, somebody different from every one else, and if for no

other reason, precious in that one could never be repeated. (Rose

Arbuthnot wonders about the child she lost, and love, Chapter 13) Another husband? Was there to be no end to them?

(Mrs. Fisher feels flooded with husbands, Chapter 13) "If he isn't nice to her," Scrap thought, "he

shall be taken to the battlements and tipped over." (Lady Caroline’s

plans for Mr. Wilkins, Chapter 14) Always being there was the essential secret for a

wife. What would have become of Mr. Fisher if she had neglected to act

on this principle she preferred not to think. Enough things became of

him as it was… (Mrs. Fisher reflects on Mr. Fisher’s infidelities,

Chapter 14) What perfect tact. Mr. Wilkins could have

worshipped her. This exquisite ignoring. Blue blood, of course, coming

out. (Mr. Wilkins admires the aristocracy’s indifference to naked

people, Chapter 14) First he bowed to the elderly lady in the doorway,

then he crossed over to her, his wet feet leaving footprints as he went,

and having got to her he politely held out his hand. (Mr. Wilkins meets

Mrs. Fisher, in only his bath towel, Chapter 14) In fact there was real conversation, and he liked

nuts. How he could have married Mrs. Wilkins was a mystery. (Mrs.

Fisher’s appraisal of Mr. Wilkins, Chapter 15) Before going to sleep that night he pinched his

wife's ear. She was amazed. These endearments . . . (Mr. Wilkins’s

idea of spousal intimacy, Chapter 15) Mrs. Fisher, aware of the value men attach to

their newly-lit cigars, could not but be impressed by this immediate and

magnificent amende honorable. (Why Mrs. Fisher approved of Mr. Wilkins

throwing his cigar into the lilies, Chapter 15) There was nothing like an intelligent, not too

young man for profitable and pleasurable companionship. (Mrs. Fisher’s

view of good, male company, Chapter 15) He was most amiable to his wife--not only in

public, which she was used to, but in private, when he certainly

wouldn't have been if he hadn't wanted to. (Mr. Wilkins and Mrs.

Wilkins at San Salvatore, Chapter 16) And the more he treated her as though she were

really very nice, the more Lotty expanded and became really very nice,

and the more he, affected in his turn, became really very nice himself…

(Mr. Wilkins discovers the effect of kindness in a marriage, Chapter 16) … in this second week he sometimes pinched both

her ears… and Lotty, marveling at such rapidly developing

affectionateness, wondered what he would do, should he continue at this

rate, in the third week, when her supply of ears would have come to an

end. (Mr. and Mrs. Wilkins’s growing intimacy, Chapter 16) He did not again have a bath in the bathroom… but

got up and went down every morning to the sea, and in spite of the cool

nights making the water cold early had his dip as a man should. (Mr.

Wilkins doing what every man should, Chapter 16) How wonderful it would be, how too wonderful, if

the place worked on him too and were able to make them even a little

understand each other, even a little be friends. (Rose Arbuthnot’s

modest expectations of Mr. Arbuthnot, Chapter 16) Why, one person in the world, one single person

belonging to one, of one's very own, to talk to, to take care of, to

love, to be interested in, was worth more than all the speeches on

platforms and the compliments of chairmen in the world. (Rose Arbuthnot

values love over her career for the first time, Chapter 16) It was such an absurd sensation at her age. Yet

oftener and oftener, and every day more and more, did Mrs. Fisher have a

ridiculous feeling as if she were presently going to burgeon. (Mrs.

Fisher feels she just might burst forth in fresh growth, Chapter 16) She herself had grown old as people should grow

old--steadily and firmly. No interruptions, no belated after-glows and

spasmodic returns. (Mrs. Fisher’s views on ageing, Chapter 16) Old friends… compare one constantly with what one

used to be. … They are surprised at development. They hark back; they

expect motionlessness after, say, fifty, to the end of one's days… It is

condemning one to a premature death. (Mrs. Fisher’s views on old

friends, Chapter 16) Prince of Wales Terrace did seem a very dark black

spot to have to go back to … with nothing really living or young in it.

… there were only the maids, and they were dusty old things. (Mrs.

Fisher fears returning home, Chapter 16) There was, however, no one who would understand

except Mrs. Wilkins herself. … But this was impossible. It would be as

abject as begging the very microbe that was infecting one for protection

against its disease. (Why Mrs. Fisher did not want to confide her

worries to Mrs. Wilkins, Chapter 16) "You are all thoughtfulness and consideration,"

declared Mr. Wilkins, wishing, for the first time in his life, that he

were a foreigner so that he might respectfully kiss her hand… (Why

Englishman Mr. Wilkins wished he were foreign, Chapter 16) Lotty was evidently, then, that which before

marriage he had believed her to be--she was valuable. (Why Mr. Wilkins

married Mrs. Wilkins, Chapter 16) Such a jumble of spring and summer was not to be

believed in, except by those who dwelt in those gardens. Everything

seemed to be out together--all the things crowded into one month which

in England are spread penuriously over six. (The difference between an

Italian garden and an English garden, Chapter 16) For now that Rose was not able to say her prayers

she was being assailed by every sort of weakness: vanity,

sensitiveness, irritability, pugnacity --strange, unfamiliar devils to

have coming crowding on one and taking possession of one's swept and

empty heart. (Repressed Rose Arbuthnot encounters what she has been

repressing, Chapter 17) How passionately she longed to be important to

somebody again--not important on platforms, not important as an asset in

an organization, but privately important, just to one other person,

quite privately, nobody else to know or notice. (Rose Arbuthnot is

prepared to reject career for love, Chapter 17) And Mr. Wilkins, much pleased with her, though it

was still quite early in the day, a time when caresses are sluggish,

pinched her ear. (Mr. Wilkins believes marital intimacy has a time and

place, Chapter 17) At the sight of him Francesca flung up every bit

of her that would fling up--eyebrows, eyelids, and hands, and volubly

assured him that all was in perfect order and that she was doing her

duty. (Italian enthusiasm and expressiveness through the eyes of an

Englishman, Chapter 17) Since even the most religious, sober women like to

know they have made an impression, particularly the kind that has

nothing to do with character or merits, Rose was pleased. (A reflection

on female vanity, Chapter 18) It wanted that final touch of warmth and beauty,

for he never thought of his wife except in terms of warmth and

beauty--she would of course be beautiful and kind. It amused him how

much in love with this vague wife he was already. (Mr. Briggs’s view of

San Salvatore and a wife, Chapter 18) She liked property, and she liked men of

property. Also there seemed a peculiar merit in being a man of property

so young. Inheritance, of course; and inheritance was more respectable

than acquisition. (Why Mrs. Fisher liked Mr. Briggs, Chapter 18) … was it not better to feel young somewhere rather

than old everywhere? (Mrs. Fisher’s new view on life at San Salvatore,

Chapter 18) "Upon my word," thought Mrs. Fisher, "the way one

pretty face can turn a delightful man into an idiot is past all

patience." (Mrs. Fisher’s reaction to Mr. Briggs’s reaction to Lady

Catherine, Chapter 19) This tyranny of one person over another! (Lady

Catherine’s irritation with men slavish to her exterior beauty, Chapter

19) … Lotty, who never wanted anything of anybody, but

was complete in herself and respected other people's completeness? One

loved being with Lotty. With her one was free, and yet befriended.

(Lady Catherine’s reasons for liking Mrs. Wilkins, Chapter 19) What fun it had been, having an admirer even for

that little while. No wonder people liked admirers. They seemed, in

some strange way, to make one come alive. (Why Rose Arbuthnot had

accepted Mr. Briggs’s attentions, Chapter 20) … this delicate, pervading warmth… Yes;

security. No need now to be ashamed of his figure… Rose cared nothing

for such things. With her he was safe. To her he was her lover, as he

used to be; and she would never notice or mind any of the ignoble

changes that getting older had made in him and would go on making more

and more. (Mr. Arbuthnot recognizes the comfort of married love,

Chapter 21) But this Rose was his youth again, the best part

of his life… It was wonderful to have it all come back to him at the

touch of her, at the feel of her face against his--wonderful that she

should be able to give him back his youth. (Mr. Arbuthnot reflects on

his wife’s ability to make him feel young again, Chapter 21) "This," thought Mrs. Fisher, "must now be the last

of the husbands, unless Lady Caroline produces one from up her sleeve."

(Mrs. Fisher’s reaction to the second ‘widow’ producing a husband,

Chapter 21) She sees what we can't see, because she loves

him. (Mrs. Wilkins explains why Mrs. Arbuthnot loves Mr. Arbuthnot,

Chapter 22) And what was she, thanks to this love Lotty talked

so much about? Scrap searched for a just description. She was a

spoilt, a sour, a suspicious, and a selfish spinster. (Lady Catherine

recognizes what too many arduous and insistent men had made her, Chapter

22) She craved for the living, the developing--the

crystallized and finished wearied her. She was thinking that if only

she had had a son--a son like Mr. Briggs, a dear boy like that, going

on, unfolding, alive, affectionate, taking care of her and loving her. .

. (What Mrs. Fisher really wanted at this point in her life, Chapter

22) It did seem that people could only be really happy

in pairs--any sorts of pairs, not in the least necessarily lovers, but

pairs of friends, pairs of mothers and children, of brothers and

sisters--and where was the other half of Mrs. Fisher's pair going to be

found? (Mrs. Wilkins’s view of happiness, Chapter 22) "I believe I'm the other half of her pair,"

flashed into her mind. "I believe it's me, positively me, going to be

fast friends with Mrs. Fisher!" (Mrs. Wilkins’s realization, Chapter

22) Visit my Italian Garden page.

Enchanted April in an Italian Castle and Garden - Elizabeth von

Arnim

![]()

The novella, and basis

of the 1992 film of the same name, was The Enchanted April by

Elizabeth von Arnim. It is an italophile favorite, just like the

film and novella A Room with a View is, for similar reasons:

the idyllic, soul-reparative Italian setting.

Quotes from

The Enchanted April