Candida Martinelli's Italophile Site

Main

Page This family-friendly site celebrates Italian culture for the enjoyment of children and

adults. Site-Overview

Wallace Breem's Eagle in the Snow is

widely recognized as a modern classic in the historical fiction

genre, creating living characters, set in a factually correct

past, that is brought to life through the skill of the writer. He

has inspired historical novelists since this novel first came out in

1970. You'll find many elements of his novels and characters

in the books by Lindsay Davis (Marcus Didius Falco Mystery Series) and Steven Saylor (Gordianus the Finder

Mystery series). And the Italian novelist Valerio Massimo

Manfredi's book The Last Legion, which was made into a film

of the same name, takes up the Excalibur plotline that is suggested

by a line near the end of Eagle in the Snow. Eagle in the Snow was recently re-released in both hardback and

paperback (although it is still hard to come by).

And there are plenty of

second-hand copies in circulation.

There is, again, talk

of adapting it to film. Interest in the book was

renewed partly because the character of Maximus, Quintus and others

that appeared in the Oscar-winning film Gladiator, were

inspired at least in part by Mr. Breem’s characters.

And the opening sequence of the film, on the Eastern border of

the Roman Empire, was straight from Mr. Breem’s book. Many Eagle in the Snow

fans regret that Gladiator only took a few characters and

settings, rather than adapted the whole novel.

They all agree that Breem’s story is far superior to the Gladiator

story, which is mainly a mash-up of old Hollywood Roman-Swords-and-Sandals movies. Wallace Breem's book covers

most of the life of Maximus, a fictional Roman General,

who recounts his story to some defeated peasants in Cornwall,

England. As he recounts, over the course of Maximus's career,

he

defends the Roman Empire from invasion by hordes from the North, and

then the East under Roman General Stilicho (roughly present day France from present day Germany). Maximus is a perfect Roman

soldier: brave, orderly, rigorous, dedicated, honorable and

dependable. He is a staid and stolid man whose greatest pride

is in his self-discipline and the forces under him. So he is

understandably

shamed to see the poor state of Rome's famous legions as the

Empire crumbles under the continued attacks from tribes outside the

Empire's frontiers (limes).

He puts up a thankless

struggle against a unified force of invaders both in the North and

in the East. But the winter invasions by barbarian tribes over the frozen Rhine River in 406-407,

which he attempts to counter, are often

sited as the beginning of the end of the Roman Empire, as Breem

recounts in his book through

stolid

Maximus's account. You should read the rave

reader reviews at both Amazon.com

and Barnes

and Noble. Because we know in advance the sad outcome of all

of poor Maximus's commands, I found the book rather sad and

depressing, but also full of painfully real characters set in a

meticulously imagined past that is painted with a light touch.

Maximus's stolid character produces many moments of poignancy.

I had to read the book in small doses so as not to become to

depressed by the story. One reader-reviewer wrote: "...there is a

poignant Latin coda at the end of the original text, along the lines

of a Roman funerary inscription, that is MISSING from both Rugged Land

editions (hardback and paperback) -- how do these things happen? Shame

on the publisher. This ties up some lingering questions about how

Maximus' narrative came to be and is a fitting sign-off to this

powerful story." Here is that funerary epitaph, that is an answer

to Maximus's near final statement that none of the soldiers from the

Eastern front were commemorated on funerary (grave) stones, as was a

Roman tradition, just in case your edition is

missing it: DIS MANIBUS And a rough translation (please contact me if you

have a better one): To

the spirits of the departed (To the gods of the afterlife, or in

today's wording 'In Loving Memory')

For Paulinus

Gaius Maximus son of Claudius Arelatis, Prefectus

of the First Cohort of Tungrians, and Legate of the Twentieth Legion Valeria Victrix, Commander

in Chief at Mainz, Count in charge of the defense of Gaul

who died aged 57, and for Quintus Veronius, Prefectus of

the Petriana Wing, and Prefectus of the Second Cohort Asturias, and Master

of the Horse (Head of the Cavalry) for Upper Germany, who died in his 56th year

in the Battle of the Rhine.

Their

friend Saturninus erected this. The womanizing, drinking, gambling,

master-horseman character of Quintus Veronius, one of Maximus's

closest friends, appears to be a precursor of the protagonist of

Breem's next novel, The Legate's Daughter, Curtius Rufus, who

may be based on the Roman senator, historian and self-made man of

obscure background, Quintus Curtius Rufus. If you're into battle scenarios and war-games,

check out this fan's

analysis of Maximus's battles to defend the Roman Empire's Eastern

flank. "Banished to the Empire’s farthest outpost, veteran warrior

Paulinus Maximus defends The Wall of Britannia from the constant

onslaught of belligerent barbarian tribes. Bravery, loyalty,

experience, and success lead to Maximus’ appointment as

"General of the West" by the Roman emperor, the ambition of

a lifetime. But with the title comes a caveat: Maximus needs to

muster and command a single legion to defend the perilous Rhine

frontier.

I have read this book (C.M.)

and I found it an intriguing read. The author departs from his

first book (Eagle in the Snow) which shows in intimate detail the

skills and character needed to head an Ancient Roman legion at the

border of the Empire. Instead, The Legate's Daughter shows

in intimate detail the skills and characters needed to run a

diplomatic mission at the edge of the Ancient Roman Empire. The reader is put in the position of a diplomat, someone who must

collect gossip, read people, and read between the lines

in this third-person narrated novel. Nothing

is spelled out for the reader. We must move along with the

characters and try to cipher out the truth, the good guys and the bad

guys from the events, glances, words, sighs, and chance encounters. The protagonist is Curtius Rufus. He is spotted by Maecenas, a

real-life master diplomat, and by Marcus Agrippa, a real-life soldier

and administrator, who has had to rely on Maecenas's diplomatic skills

more then once. The two men tutor Curtius, then send him on a

delicate and impossible mission: to recover the daughter of a

Roman patrician and senator, who has been taken by force from Spain and

who is likely hidden somewhere in North Africa. Breen has created in Curtius Rufus a whole character, full of

contradictions, talents, weaknesses and all the natural skills needed by

a diplomat who has to deal with the tribes at the edge of the Roman

Empire: guile, intuition, sharp reasoning, people reading,

languages, gossip mongering, seduction, conversation that convinces and

that induces confidence, patience, tactical tricks, leadership,

sacrifice, friendship, loyalty. Curtius is a man in a man's world, but he also understands

those at the weak end of the harsh society: the slaves (his father

was one), the freedmen (he is one), the Roman outsiders (his best friend

is one), the women (his greatest skill is his ability to seduce and

please women). It is possible that Breem created his character with the

historian/politician Quintus Curtius Rufus, sometimes called Curtius

Rufus, in mind. The Roman writer Tacitus tells us what little

we know about Rufus, and it fits very closely with Breem's

character, in moody temperament and ambitious new-man status, which

was a self-made man from obscure birth. That would mean that

Breem's Rufus goes on after the end of the book to have a very long

life and career leading to a Praetorship, a Consulship, a Triumph

(not for military triumphs but for commercial ones), and as a

writer, and lastly as Proconsul of Africa, where he presumably died,

a very old man. The book is rich with period detail, so rich that it seems to be

written by someone who lived through the events described. No, I

mean REALLY lived there. So many historical novels purport to be

first person accounts of events and fall short, but we make excuses for

the writer, saying "Well, it is set in in a date from before the birth

of Christ...". This book has the richness that leaves you feeling

that you have visited the times and places described.

This is not an easy read. Many times I had to set the book down

and head for the Internet to look up the history, geography and people

of Ancient Rome. I'm not complaining. I enjoyed that.

But a warning to readers who like everything handed to them on a

plate: to read the book without the historical information would

be a waste of time. Breem's first novel was written as a gift to

his wife. This novel reads like a gift to every classicist on the

planet. There is so much for the knowledgeable reading to enjoy.

This means that you, the reader, must assemble the plot in your mind as

you read, as if you were decoding a diplomatic message.

Challenging, yes. Rewarding, most definitely yes! It is

the kind of book that you read to the last page then you start all over

again at page one, to make sure you've really understood everything that

happened. I read it, did lots of research, then read it again, and

I enjoyed it even more the second time around! (This profile was published previously in Solander,

the the magazine of the Historical Novel Society, and is authored by

Mr. Alan Fisk (see below).) In

1970, the Times Literary Supplement ran a dismissive

review of a new historical novel called Eagle in the Snow, by

an unknown writer called Wallace Breem. The

review was read by no less a personage than Mary Renault, who sent a

scathing letter to the TLS, praising the book and lambasting

the reviewer. Eagle in the Snow became a major success,

being reprinted twice within the same year, and Wallace Breem seemed

set to become one of the big names in historical fiction. In

July 2002 Eagle in the Snow will be reissued by Phoenix Press.

(A full review of Eagle in the Snow will appear in a future

issue of The Historical Novels Review.) Negotiations are in

progress for a possible film. Sadly, Wallace Breem himself cannot

enjoy this success, having died in 1990, but his widow Mrs. Rikki

Breem kindly granted an interview to Solander to help with this

article. The

interest in the novel and a film partly arise because the Roman

general Maximus, the hero of Eagle

in the Snow was an inspiration for the Roman general Maximus,

the hero of the film Gladiator. Eagle

in the Snow covers a period of over 30 years, starting in

late fourth-century Britain, and finishing in a harrowing climax when

the freezing-over of the river Rhine on 31 December 406 allows a vast

horde of Germanic barbarians to pour into the western provinces of the

Empire. Maximus is a loyal officer and husband, and a devotee of the

cult of Mithras, but his steadfastness is not repaid by loyalty on the

part of those close to him. This Maximus is no tiger-fighting

gladiator, but a passionate and unhappy man driven into deep waters

against his will. Breem

achieved his ambition, and was commissioned into the Queen

Victoria’s Own Corps of Guides, a very distinguished regiment

that had long served on the Northwest Frontier. He

looked forward to a lifelong career in the Guides, apparently not

foreseeing that there would be no place for men like him in the

independent India that was soon to come into being. His years in the

Guides would always haunt him. Upon

Partition in 1947, Wallace Breem left the Army and sailed back to

England, with no plan at all for his life. He had so wanted to make a

career in the Guides. On

the voyage home, Breem began writing the novel that would one day

appear after many revisions as his third novel, The Leopard and the

Cliff, of which more later. When

he arrived home Breem took a series of short-term casual jobs, not

really knowing what to do with himself. He worked as an assistant to a

veterinary surgeon, spent some time working in a tannery, and for a

while he was a rent collector in the East End of London, a job which

was perhaps nearly as dangerous as his combat service on the Northwest

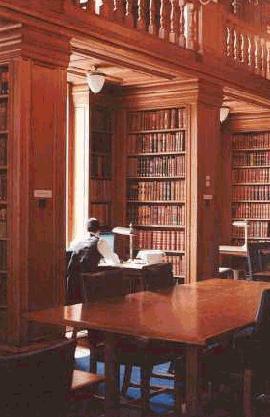

Frontier. Eventually

an acquaintance suggested that he join the staff of the Inner

Temple legal library. Breem had no training or experience in legal

librarianship. Today nobody would get such a job without a handful of

appropriate certificates, but in the 1940s character counted for more

than paper qualifications. Wallace Breem settled into the Inner Temple

library, where he would work for the rest of his life. There

was much to do. A large part of the Inner Temple’s 500-year-old

collection had been lost to enemy air raids in 1941/2, because of a

stubborn decision not to move it out of London. Breem started as an

Assistant, and then became a Sub-Librarian in 1956. While

he spent his working life in the library, Wallace Breem had never lost

his interest in writing and in history. He had kept the manuscript of The

Leopard and the Cliff, and planned several other novels. As

he rose through the ranks of the Inner Temple library, Breem was also

busy writing. Over the years he experienced frustration as a

succession of promising schemes came to nothing. At one stage a

publisher had asked him to write a book for children, but it was

cancelled. In

1965 Wallace Breem became Chief Librarian and Keeper of Manuscripts,

and in the following year he married his Deputy Librarian Daphne

“Rikki” Parnham. When asked to list his interests, he cited

“Books and Reading, Poetry, Music, Theatre, Early Cinema, Ancient,

Mediæval and Military History, Travel, and Cats”. Oddly,

the list does not include any reference to writing historical fiction.

Eagle in the Snow had originated as a short story that he had

written as a Christmas present for Rikki, but as he worked on the

story it became longer and longer until it turned into a novel. When

Eagle in the Snow became Wallace Breem’s first published

novel, he was already 54, but it had been worth waiting for. After

that first scornful review in the Times

Literary Supplement, the praise rolled in from all directions.

Mary Renault described it as “Pure pleasure... I had to stop reading

it at night - its intense reality kept me awake”, and R.C. Sheriff

said “It springs to life on the first page and never falters”. Eagle

in the Snow was reprinted twice in its first year, and there was

already talk of filming it. Breem himself always wanted Charlton

Heston to play the part of Maximus! Wallace

Breem set his stories, where possible, in places that he had visited

himself. If that was not possible, he researched them thoroughly. His

second novel, The Legate’s Daughter, was largely set in

Tunisia, a country that he did not see until after the book had been

published. The

first half of The Legate’s Daughter is set in Rome in 24

B.C., where the former centurion Curtius Rufus is working as an

unenthusiastic civil servant in the water-supply office of the city. Curtius

Rufus and his friend the unsuccessful Macedonian poet Criton are

forced to travel to North Africa, ostensibly to help the young

Mauretanian client king Juba to set up a programme of building works,

but really to try to recover a teenage girl, the legate’s daughter

of the title, who has been abducted to unknown whereabouts. Curtius

Rufus strives to understand the complex tribal politics of the North

African kingdoms, and establishes a close but troubled relationship

with Juba’s queen, Cleopatra Selene, the daughter of Cleopatra of

Egypt. (Breem was always fascinated by Queen Cleopatra, and planned to

write about her one day.) The

Legate’s Daughter was published in 1974, but did not match the

success of Eagle in the Snow, although it has at least as many

interesting and memorable characters. Breem’s gift for creating

images that communicate the atmosphere of a distant time and place was

as strong as ever, but the book does not quite have the grip of Eagle

in the Snow.

After another four years, The Leopard and the Cliff,

which Breem had first written on that unwanted voyage back from India

30 years before, was published in its final form. It

is based loosely on a real incident from the nearly-forgotten Third

Afghan War, which lasted for only 26 days in 1919. Sandeman

considers himself to be a mediocrity and a failure. Apart from his own

situation, he is also concerned for his much younger wife Sophie, who

is expecting their first child. She is 300 miles away, and Sandeman

has not seen her for four months. He

has to recall his officers and men to the fort at Khaisora, and to try

to keep the Scouts together although they are drawn from several

tribes with a history of mutual distrust. Sandeman has to abandon

Khaisora and lead his column on a long march through territory where

both the land and its inhabitants are their enemies. If

you think that all Northwest Frontier novels are the same, this one is

different. Major Sandeman’s struggles against his enemies, against

the harsh conditions of Waziristan, and against his own doubts about

his abilities, make an intensely moving story all the way until the

very last pages of this novel, when the last survivors of the Scouts

struggle to the end of the march at Fort Gumal. The

Leopard and the Cliff shares a common theme with Wallace Breem’s

other two novels: a man has great responsibilities thrust upon him

that he did not seek, and does his best to discharge them and protect

his companions. His heroes also always face treachery and betrayal

from those whom they should be able to trust. Breem

planned a fourth novel, about the disaster to the Roman general Varrus

who lost three legions in the Teutoberg forest in Germany in 9 A.D.,

but he never completed it. The success of Eagle in the Snow had

proved a false dawn, and he never became a full-time writer of

historical novels. In

any case, Wallace Breem’s time was filled by his work as a legal

librarian. He used his writing skills in that field as well, making an

important contribution to the standard Manual of Law Librarianship. Breem

never lost his love of historical fiction. He acted as an adviser on

military matters to Rosemary Sutcliff, notably in her Frontier Wolf. He planned a novel about Richard III, with his usual high

standards of research. Rikki Breem remembers accompanying him around

the site of the battle of Barnet. He still dreamt of a novel about

Cleopatra. Meanwhile,

readers who had been delighted by Eagle in the Snow and

its successors wondered what had become of the promising Wallace

Breem. Few of them knew that he was probably the country’s leading

law librarian, an occupation which most people would have thought

suited to a dry-as-dust pedant, not to a man of action like Wallace

Breem. General

Maximus honored by his legionnaires in the film Gladiator. (Roman

history buffs and film pundits have pointed out that Romans did not

use stirrups at that time. But the actors did, because riding a

horse Roman style is very, very difficult! Others point out that

the Roman costumes in the film are all from the wrong time

periods. One person even complained that the point on the top of

a helmet wiggled as the fighter ran, showing it to be made of

rubber. And a spectator in the Forum was spotted wearing

designer sunglasses.) After

his death, the British and Irish Association of Law Librarians set up

the Wallace Breem award for legal librarianship in his honour. In

Wallace Breem’s obituary in The Independent, Bruce Coward

wrote that “...writing of his quality is seldom found in historical

writing today. All his books have long been out of print, but deserve

reprinting, because they would surely delight those readers who look

for integrity as well as excitement in their historical fiction”. The

reissue of Eagle in the Snow, and the film of it if it is made,

will attract a new audience for the historical novels of this

thoughtful writer, who was so skilled at creating characters and

atmosphere that always live on in the memory of his readers. (As well

as thanking Mrs. Rikki Breem, Solander would like to express

its appreciation to Ms. Margaret Clay, the present Librarian and

Keeper of Manuscripts at the Inner Temple, for her help in the

preparation of this article.) Alan

Fisk

is the author of The Strange Things of the World (1988), The

Summer Stars (1992 and 2000), Forty Testoons (1999),

and Lord of Silver (2001), and Cupid and the Silent

Goddess (2003). His website. From Reviews: "...captures the atmosphere of sixteenth-century Florence and

the world of the artists excellently. this is a fascinating

imaginative reconstruction of the events during the painting of

Allegory with Venus and Cupid." Marina Oliver, historical

novelist. "A witty and entertaining romp set in the seedy world of

Italian Renaissance artists." Elizabeth Chadwick, award-winning

historical novelist. You can read

the first chapter on-line, and reviews from other authors. The painting on the cover, and described in the book, is by

Bronzino and is currently in the collection at the National

Gallery in London. Another look at the painting...

More

About Wallace Breem...

![]()

Eagle

in the Snow

P GAIO MAXIMO FILIO CLAUDII ARELATIS

PRAEFECTUS I COH TUNG LEG XX VAL VIC

DUX MOGUNTIACENSIS COMES GALLIARUM

ANN LVII CCCX ET Q VERONIO PRAEFECTUS

ALAE PETRIAE PRAEFECTUS II COH ASTUR

MAGISTER EQUITUM GERMANIAE SUPER ANN

LVI CECIDIT BELLO RHENO CCCCVII

SATURNINUS AMICUS FECITFrom The Publisher:

On

the opposite side of the Rhine River, tribal nations are uniting;

hundreds of thousands mass in preparation for the conquest of Gaul,

and from there, a sweep down into Rome itself. Only a wide river

and a wily general keep them in check.

On

the opposite side of the Rhine River, tribal nations are uniting;

hundreds of thousands mass in preparation for the conquest of Gaul,

and from there, a sweep down into Rome itself. Only a wide river

and a wily general keep them in check.

With discipline, deception, persuasion, and surprise, Maximus holds

the line against an increasingly desperate and innumerable foe.

Friends, allies, and even enemies urge Maximus to proclaim himself

emperor. He refuses, bound by an oath of duty, honor, and

sacrifice to Rome, a city he has never seen. But then

circumstance intervenes. Now, Maximus will accept the purple

robe of emperor, if his scrappy legion can deliver this last crucial

victory against insurmountable odds. The very fate of Rome hangs

in the balance.

Combining the brilliantly realized battle action of Gates of Fire

[by Stephen Pressfield] and

the masterful characterization of Mary Renault's The Last of the

Wine, Eagle in the Snow is nothing less than the novel of the fall

of the Roman empire."Wallace Breem's

The Legate's Daughter

Profile of Wallace

Breem by Alan Fisk

Wallace

Breem was born in 1926, and went to Westminster School. As a boy, he

developed a desire to serve in the Indian Army, a desire which was

kindled by the books of Rudyard Kipling and by seeing Gary Cooper in The

Lives of a Bengal Lancer. The 1930s Saturday cinema matinées have

much to answer for.

Wallace

Breem was born in 1926, and went to Westminster School. As a boy, he

developed a desire to serve in the Indian Army, a desire which was

kindled by the books of Rudyard Kipling and by seeing Gary Cooper in The

Lives of a Bengal Lancer. The 1930s Saturday cinema matinées have

much to answer for.

The

character of the ex-soldier Curtius Rufus, and the louche Rome in

which he lives, oddly prefigure the “Falco” novels of Lindsey

Davis.

The

character of the ex-soldier Curtius Rufus, and the louche Rome in

which he lives, oddly prefigure the “Falco” novels of Lindsey

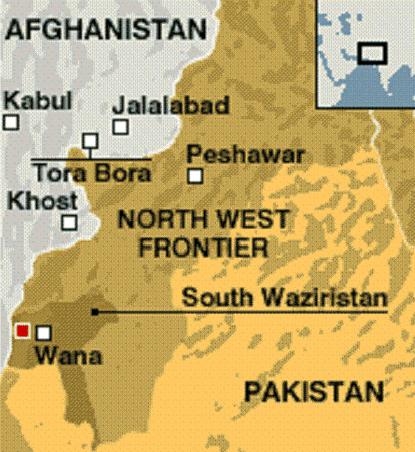

Davis. Major

Sandeman of the Khaisora Scouts, a regiment recruited from Pathans and

other tribes of Waziristan on the Northwest Frontier, is in acting

command of the fort of Khaisora when he receives a signal that a large

force has crossed over from Afghanistan and is attacking the scattered

outposts.

Major

Sandeman of the Khaisora Scouts, a regiment recruited from Pathans and

other tribes of Waziristan on the Northwest Frontier, is in acting

command of the fort of Khaisora when he receives a signal that a large

force has crossed over from Afghanistan and is attacking the scattered

outposts.

Cupid

and the Silent Goddess

Cupid

and the Silent Goddess