Candida Martinelli's Italophile Site

Main

Page This family-friendly site celebrates Italian culture for the enjoyment of children and

adults. Site-Overview

Knights of Art -

Sandro Botticelli

Visit

my Angels in Italian Art Page

Visit

my Canaletto and Venice Art Page On-line

images of art at Web Gallery

of Art: We

must now go back to the days when Fra Filippo Lippi painted his pictures

and so brought fame to the Carmine Convent. There

was at that time in Florence a good citizen called Mariano Filipepi, an

honest, well-to-do man, who had several sons. These sons were all taught

carefully and well trained to do each the work he chose. But the fourth

son, Alessandro, or Sandro as he was called, was a great trial to his

father. He would settle to no trade or calling. Restless and uncertain,

he turned from one thing to another. At one time he would work with all

his might, and then again become as idle and fitful as the summer

breeze. He could learn well and quickly when he chose, but then there

were so few things that he did choose to learn. Music he loved, and he

knew every song of the birds, and anything connected with flowers was a

special joy to him. No one knew better than he how the different kinds

of roses grew, and how the lilies hung upon their stalks. The Virgin and Eight Angles

(detail) by Botticelli `And

what, I should like to know, is going to be the use of all this,' the

good father would say impatiently, `as long as thou takest no pains to

read and write and do thy sums? What am I to do with such a boy, I

wonder?' Then

in despair the poor man decided to send Sandro to a neighbour's

workshop, to see if perhaps his hands would work better than his head. The

name of this neighbour was Botticelli, and he was a goldsmith, and a

very excellent master of his art. He agreed to receive Sandro as his

pupil, so it happened that the boy was called by his master's name, and

was known ever after as Sandro Botticelli. Sandro

worked for some time with his master, and quickly learned to draw

designs for the goldsmith's work. In

those days painters and goldsmiths worked a great deal together, and

Sandro often saw designs for pictures and listened to the talk of the

artists who came to his master's shop. Gradually, as he looked and

listened, his mind was made up. He would become a painter. All his

restless longings and day dreams turned to this. All the music that

floated in the air as he listened to the birds' song, the gentle dancing

motion of the wind among the trees, all the colours of the flowers, and

the graceful twinings of the rose-stems--all these he would catch and

weave into his pictures. Yes, he would learn to painst music and motion,

and then he would be happy. Birth of Venus (detail) by

Botticelli `So

now thou wilt become a painter,' said his father, with a hopeless sigh. Truly

this boy was more trouble than all the rest put together. Here he had

just settled down to learn how to become a good goldsmith, and now he

wished to try his hand at something else. Well, it was no use saying

`no.' The boy could never be made to do anything but what he wished.

There was the Carmelite monk Fra Filippo Lippi, of whom all, men were

talking. It was said he was the greatest painter in Florence. The boy

should have the best teaching it was possible to give him, and perhaps

this time he would stick to his work. So

Sandro was sent as a pupil to Fra Filippo, and he soon became a great

favourite with the happy, sunny-tempered master. The quick eye of the

painter soon saw that this was no ordinary pupil. There was something

about Sandro's drawing that was different to anything that Filippo had

ever seen before. His figures seemed to move, and one almost heard the

wind rustling in their flowing drapery. Instead of walking, they seemed

to be dancing lightly along with a swaying motion as if to the rhythm of

music. The very rose-leaves the boy loved to paint, seemed to flutter

down to the sound of a fairy song. Filippo was proud of his pupil. Birth of Venus by Botticelli `The

world will one day hear more of my Sandro Botticelli,' he said; and,

young though the boy was, he often took him to different places to help

him in his work. So

it happened that in that wonderful spring of Filippo's life, Sandro too

was at Prato, and worked there with Fra Diamante. And in later years

when the master's little daughter was born, she was named Alessandra,

after the favourite pupil, to whom was also left the training of little

Filippino. Now,

indeed, Sandro's good old father had no further cause to complain. The

boy had found the work he was most fitted for, and his name soon became

famous in Florence. It

was the reign of gaiety and pleasure in the city of Florence at that

time. Lorenzo the Magnificent, the son of Cosimo de Medici, was ruler

now, and his court was the centre of all that was most splendid and

beautiful. Rich dresses, dainty food, music, gay revels, everything that

could give pleasure, whether good or bad, was there. Lorenzo,

like his father, was always glad to discover a new painter, and

Botticelli soon became a great favourite at court. But

pictures of saints and angels were somewhat out of fashion at that time,

for people did not care to be reminded of anything but earthly

pleasures. So Botticelli chose his subjects to please the court, and for

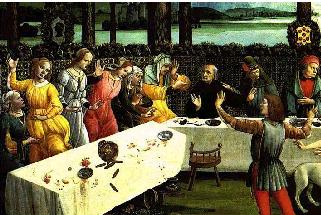

a while ceased to paint his sad-eyed Madonnas. Nastasio degli Onesto by

Botticelli What

mattered to him what his subject was? Let him but paint his dancing

figures, tripping along in their light flowing garments, keeping time to

the music of his thoughts, and the subject might be one of the old Greek

tales or any other story that served his purpose. All

the gay court dresses, the rich quaint robes of the fair ladies, helped

to train the young painter's fancy for flowing draperies and wonderful

veils of filmy transparent gauze. There

was one fair lady especially whom Sandro loved to paint--the beautiful

Simonetta, as she is still called. First

he painted her as Venus, who was born of the sea foam. In his picture

she floats to the shore standing in a shell, her golden hair wrapped

round her. The winds behind blow her onward and scatter pink and red

roses through the air. On the shore stands Spring, who holds out a

mantle, flowers nestling in its folds, ready to enwrap the goddess when

the winds shall have wafted her to land. Then

again we see her in his wonderful picture of `Spring,' and in another

called `Mars and Venus.' She was too great a lady to stoop to the humble

painter, and he perhaps only looked up to her as a star shining in

heaven, far out of the reach of his love. But he never ceased to worship

her from afar. He never married or cared for any other fair face, just

as the great poet Dante, whom Botticelli admired so much, dreamed only

of his one love, Beatrice. La Primavera by Botticelli But

Sandro did not go sadly through life sighing for what could never be

his. He was kindly and good-natured, full of jokes, and ready to make

merry with his pupils in the workshop. It

once happened that one of these pupils, Biagio by name, had made a copy

of one of Sandro's pictures, a beautiful Madonna surrounded by eight

angels. This he was very anxious to sell, and the master kindly promised

to help him, and in the end arranged the matter with a citizen of

Florence, who offered to buy it for six gold pieces. `Well,

Biagio,' said Sandro, when his pupil came into the studio next morning,

`I have sold thy picture. Let us now hang it up in a good light that the

man who wishes to buy it may see it at its best. Then will he pay thee

the money.' Biagio

was overjoyed. `Oh,

master,' he cried, `how well thou hast done.' Then

with hands which trembled with excitement the pupil arranged the picture

in the best light, and went to fetch the purchaser. Now

meanwhile Botticelli and his other pupils had made eight caps of scarlet

pasteboard such as the citizens of Florence then wore, and these they

fastened with wax on to the heads of the eight angels in the picture. Presently

Biagio came back panting with joyful excitement, and brought with him

the citizen, who knew already of the joke. The poor boy looked at his

picture and then rubbed his eyes. What had happened? Where were his

angels? The picture must be bewitched, for instead of his angels he saw

only eight citizens in scarlet caps. Coronation (detail) by

Botticelli He

looked wildly around, and then at the face of the man who had promised

to buy the picture. Of course he would refuse to take such a thing. But,

to his surprise, the citizen looked well pleased, and even praised the

work. `It

is well worth the money,' he said; `and if thou wilt return with me to

my house, I will pay thee the six gold pieces.' Biagio

scarcely knew what to do. He was so puzzled and bewildered he felt as if

this must be a bad dream. As

soon as he could, he rushed back to the studio to look again at that

picture, and then he found that the red-capped citizens had disappeared,

and his eight angels were there instead. This of course was not

surprising, as Sandro and his pupils had quickly removed the wax and

taken off the scarlet caps. `Master,

master,' cried the astonished pupil, `tell me if I am dreaming, or if I

have lost my wits? When I came in just now, these angels were Florentine

citizens with red caps on their heads, and now they are angels once

more. What may this mean?' `I

think, Biagio, that this money must have turned thy brain round,' said

Botticelli gravely. `If the angels had looked as thou sayest, dost thou

think the citizen would have bought the picture?' `That

is true,' said Biagio, shaking his head solemnly; `and yet I swear I

never saw anything more clearly.' And

the poor boy, for many a long day, was afraid to trust his own eyes,

since they had so basely deceived him. But

the next thing that happened at the studio did not seem like a joke to

the master, for a weaver of cloth came to live close by, and his looms

made such a noise and such a shaking that Sandro was deafened, and the

house shook so greatly that it was impossible to paint. Madonna and Child with Angels

by Botticelli But

though Botticelli went to the weaver and explained all this most

courteously, the man answered roughly, `Can I not do what I like with my

own house?' So Sandro was angry, and went away and immediately ordered a

great square of stone to be brought, so big that it filled a wagon. This

he had placed on the top of his wall nearest to the weaver's house, in

such a way that the least shake

would bring it crashing down into the enemy's workshop. When

the weaver saw this he was terrified, and came round at once to the

studio. `Take

down that great stone at once,' he shouted. `Do you not see that it

would crush me and my workshop if it fell?' `Not

at all,' said Botticelli. `Why should I take it down? Can I not do as I

like with my own house?' And

this taught the weaver a lesson, so that he made less noise and shaking,

and Sandro had the best of the joke after all. There

were no idle days of dreaming now for Sandro. As soon as one picture was

finished another was wanted. Money flowed in, and his purse was always

full of gold, though he emptied it almost as fast as it was filled. His

work for the Pope at Rome alone was so well paid that the money should

have lasted him for many a long day, but in his usual careless way he

spent it all before he returned to Florence. Perhaps

it was the gay life at Lorenzo's splendid court that had taught him to

spend money so carelessly, and to have no thought but to eat, drink, and

be merry. But very soon a change began to steal over his life. The Three Graces by Botticelli There

was one man in Florence who looked with sad condemning eyes on all the

pleasure-loving crowd that thronged the court of Lorenzo the

Magnificent. In the peaceful convent of San Marco, whose walls the

angel-painter had covered with pictures `like windows into heaven,' the

stern monk Savonarola was grieving over the sin and vanity that went on

around him. He loved Florence with all his heart, and he could not bear

the thought that she was forgetting, in the whirl of pleasure, all that

was good and pure and worth the winning. Then,

like a battle-cry, his voice sounded through the city, and roused the

people from their foolish dreams of ease and pleasure. Every one flocked

to the great cathedral to hear Savonarola preach, and Sandro Botticelli

left for a while his studio and his painting and became a follower of

the great preacher. Never again did he paint those pictures of earthly

subjects which had so delighted Lorenzo. When he once more returned to

his work, it was to paint his sad-eyed Madonnas; and the music which

still floated through his visions was now like the song of angels. The

boys of Florence especially had grown wild and rough during the reign of

pleasure, and they were the terror of the city during carnival time.

They would carry long poles, or `stili,' and bar the streets across,

demanding money before they would let the people pass. This money they

spent on drinking and feasting, and at night they set up great trees in

the squares or wider streets and lighted huge bonfires around them. Then

would begin a terrible fight with stones, and many of the boys were

hurt, and some even killed. No

one had been able to put a stop to this until Savonarola made up his

mind that it should cease. Then, as if by magic, all was changed. Instead

of the rough game of `stili,' there were altars put up at the corners of

the streets, and the boys begged money of the passers-by, not for their

feasts, but for the poor. The Annunciation by Botticelli `You

shall not miss your bonfire,' said Savonarola; `but instead of a tree

you shall burn up vain and useless things, and so purify the city.' So

the children went round and collected all the `vanities,' as they were

called--wigs and masks and carnival dresses, foolish songs, bad books,

and evil pictures; all were heaped high and then lighted to make one

great bonfire. Some

people think that perhaps Sandro threw into the Bonfire of Vanities some

of his own beautiful pictures, but that we cannot tell. Then

came the sad time when the people, who at one time would have made

Savonarola their king, turned against him, in the same fickle way that

crowds will ever turn. And then the great preacher, who had spent his

life trying to help and teach them, and to do them good, was burned in

the great square of that city which he had loved so dearly. After

this it was long before Botticelli cared to paint again. He was old and

weary now, poor and sad, sick of that world which had treated with such

cruelty the master whom he loved. One

last picture he painted to show the triumph of good over evil. Not with

the sword or the might of great power is the triumph won, says Sandro to

us by this picture, but by the little hand of the Christ Child,

conquering by love and drawing all men to Him. This Adoration of the

Magi is in our own National Gallery in London, and is the only painting

which Botticelli ever signed. `I,

Alessandro, painted this picture during the troubles of Italy ... when

the devil was let loose for the space of three and a half years.

Afterwards shall he be chained, and we shall see him trodden down as in

this picture.' Adoration of the Magi (detail

of de Medici) by Botticelli It

is evident that Botticelli meant by this those sad years of struggle

against evil which ended in the martyrdom of the great preacher, and he

has placed Savonarola among the crowd of worshippers drawn to His feet

by the Infant Christ. It

is sad to think of those last days when Sandro was too old and too weary

to paint. He who had loved to make his figures move with dancing feet,

was now obliged to walk with crutches. The roses and lilies of spring

were faded now, and instead of the music of his youth he heard only the

sound of harsh, ungrateful voices, in the flowerless days of poverty and

old age. There

is always something sad too about his pictures, but through the sadness,

if we listen, we may hear the angel-song, and understand it better if we

have in our minds the prayer which Botticelli left for us.

`Oh, King of Wings and Lord of Lords, who alone

rulest always in eternity, and who correctest all our wanderings, giver

of melody to the choir of angels, listen Thou a little to our bitter

grief, and come and rule us, oh Thou highest King, with Thy love which

is so sweet.'

Return to:

Stories of the Italian Painters

by Amy Steedman