Candida Martinelli's Italophile Site

Main

Page This family-friendly site celebrates Italian culture for the enjoyment of children and

adults. Site-Overview

Knights of Art -

Giotto

Visit

my Angels in Italian Art Page

Visit

my Canaletto and Venice Art Page

On-line images of art at Web

Gallery of Art:

It

was more than six hundred years ago that a little peasant baby was born

in the small village of Vespignano, not far from the beautiful city of

Florence, in Italy. The baby's father, an honest, hard-working

countryman, was called Bondone, and the name he gave to his little son

was Giotto.

Life

was rough and hard in that country home, but the peasant baby grew into

a strong, hardy boy, learning early what cold and hunger meant. The

hills which surrounded the village were grey and bare, save where the

silver of the olive-trees shone in the sunlight, or the tender green of

the shooting corn made the valley beautiful in early spring. In summer

there was little shade from the blazing sun as it rode high in the blue

sky, and the grass which grew among the grey rocks was often burnt and

brown. But, nevertheless, it was here that the sheep of the village

would be turned out to find what food they could, tended and watched by

one of the village boys. Tuscan Hills

So

it happened that when Giotto was ten years old his father sent him to

take care of the sheep upon the hillside. Country boys had then no

schools to go to or lessons to learn, and Giotto spent long happy days,

in sunshine and rain, as he followed the sheep from place to place,

wherever they could find grass enough to feed on. But Giotto did

something else besides watching his sheep. Indeed, he sometimes forgot

all about them, and many a search he had to gather them all together

again. For there was one thing he loved doing better than all beside,

and that was to try to draw pictures of all the things he saw around

him.

It

was no easy matter for the little shepherd lad. He had no pencils or

paper, and he had never, perhaps, seen a picture in all his life. But

all this mattered little to him. Out there, under the blue sky, his eyes

made pictures for him out of the fleecy white clouds as they slowly

changed from one form to another. He learned to know exactly the shape

of every flower and how it grew; he noticed how the olive-trees laid

their silver leaves against the blue background of the sky that peeped

in between, and how his sheep looked as they stooped to eat, or lay down

in the shadow of a rock.

Nothing

escaped his keen, watchful eyes, and then with eager hands he would

sharpen a piece of stone, choose out the smoothest rock, and try to draw

on its flat surface all those wonderful shapes which had filled his eyes

with their beauty. Olive-trees, flowers, birds and beasts were there,

but especially his sheep, for they were his friends and companions who

were always near him, and he could draw them in a different way each

time they moved.

Now

it fell out that one day a great master painter from Florence came

riding through the valley and over the hills where Giotto was feeding

his sheep. The name of the great master was Cimabue, and he was the most

wonderful artist in the world, so men said. He had painted a picture

which had made all Florence rejoice. The Florentines had never seen

anything like it before, and yet it was but a strange- looking portrait

of the Madonna and Child, scarcely like a real woman or a real baby at

all. Still, it seemed to them a perfect wonder, and Cimabue was honoured

as one of the city's greatest men. Cimabue's Madonna and Child

The

road was lonely as it wound along. There was nothing to be seen but

waves of grey hills on every side, so the stranger rode on, scarcely

lifting his eyes as he went. Then suddenly he came upon a flock of sheep

nibbling the scanty sunburnt grass, and a little brown-faced

shepherd-boy gave him a cheerful `Good-day, master.'

There

was something so bright and merry in the boy's smile that the great man

stopped and began to talk to him. Then his eye fell upon the smooth flat

rock over which the boy had been bending, and he started with surprise.

`Who

did that?' he asked quickly, and he pointed to the outline of a sheep

scratched upon the stone.

`It

is the picture of one of my sheep there,' answered the boy, hanging his

head with a shame- faced look. `I drew it with this,' and he held out

towards the stranger the sharp stone he had been using.

`Who

taught you to do this?' asked the master as he looked more carefully at

the lines drawn on the rock.

The

boy opened his eyes wide with astonishment `Nobody taught me, master,'

he said. `I only try to draw the things that my eyes see.'

`How

would you like to come with me to Florence and learn to be a painter?'

asked Cimabue, for he saw that the boy had a wonderful power in his

little rough hands.

Giotto's

cheeks flushed, and his eyes shone with joy.

`Indeed,

master, I would come most willingly,' he cried, `if only my father will

allow it.'

So

back they went together to the village, but not before Giotto had

carefully put his sheep into the fold, for he was never one to leave his

work half done.

Bondone

was amazed to see his boy in company with such a grand stranger, but he

was still more surprised when he heard of the stranger's offer. It

seemed a golden chance, and he gladly gave his consent.

Why,

of course, the boy should go to Florence if the gracious master would

take him and teach him to become a painter. The home would be lonely

without the boy who was so full of fun and as bright as a sunbeam. But

such chances were not to be met with every day, and he was more than

willing to let him go.

So

the master set out, and the boy Giotto went with him to Florence to

begin his training.

The

studio where Cimabue worked was not at all like those artists' rooms

which we now call studios. It was much more like a workshop, and the

boys who went there to learn how to draw and paint were taught first how

to grind and prepare the colours and then to mix them. They were not

allowed to touch a brush or pencil for a long time, but only to watch

their master at work, and learn all that they could from what they saw

him do.

So

there the boy Giotto worked and watched, but when his turn came to use

the brush, to the amazement of all, his pictures were quite unlike

anything which had ever been painted before in the workshop. Instead of

copying the stiff, unreal figures, he drew real people, real animals,

and all the things which he had learned to know so well on the grey

hillside, when he watched his father's sheep. Other artists had painted

the Madonna and Infant Christ, but Giotto painted a mother and a baby. Madonna and Child by Giotto

And

before long this worked such a wonderful change that it seemed indeed as

if the art of making pictures had been born again. To us his work still

looks stiff and strange, but in it was the beginning of all the

beautiful pictures that belong to us now.

Giotto

did not only paint pictures, he worked in marble as well. Today, if you

walk through Florence, the City of Flowers, you will still see its

fairest flower of all, the tall white campanile or bell- tower, `Giotto's

tower' as it is called. There it stands in all its grace and loveliness

like a tall white lily against the blue sky, pointing ever upward, in

the grand old faith of the shepherd-boy. Day after day it calls to

prayer and to good works, as it has done all these hundreds of years

since Giotto designed and helped to build it. Giotto's Bell-tower in

Florence

Some

people call his pictures stiff and ugly, for not every one has wise eyes

to see their beauty, but the loveliness of this tower can easily be seen

by all. `There the white doves circle round and round, and rest in the

sheltering niches of the delicately carved arches; there at the call of

its bell the black-robed Brothers of Pity hurry past to their works of

mercy. There too the little children play, and sometimes stop to stare

at the marble pictures, set in the first story of the tower, low enough

to be seen from the street. Their special favourite is perhaps the

picture of the shepherd sitting under his tent, with the sheep in front,

and with the funniest little dog keeping watch at the side.

Giotto

always had a great love for animals, and whenever it was possible he

would squeeze one into a corner of his pictures. He was sixty years old

when he designed this wonderful tower and cut some of the marble

pictures with his own hand, but you can see that the memory of those old

days when he ran barefoot about the hills and tended his sheep was with

him still. Just such another little puppy must have often played with

him in those long-ago days before he became a great painter and was

still only a merry, brown-faced boy, making pictures with a sharp stone

upon the smooth rocks.

Up

and down the narrow streets of Florence now, the great painter would

walk and watch the faces of the people as they passed. And his eyes

would still make pictures of them and their busy life, just as they used

to do with the olive-trees, the sheep, and the clouds.

In

those days nobody cared to have pictures in their houses, and only the

walls of the churches were painted. So the pictures, or frescoes, as

they were called, were of course all about sacred subjects, either

stories out of the Bible or of the lives of the saints. And as there

were few books, and the poor people did not know how to read, these

frescoed walls were the only story-books they had.

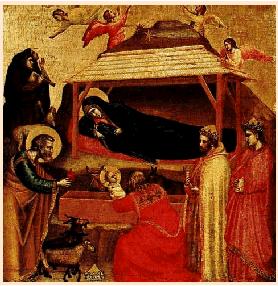

What

a joy those pictures of Giotto's must have been, then, to those poor

folk! They looked at the little Baby Jesus sitting on His mother's knee,

wrapped in swaddling bands, just like one of their own little ones, and

it made Him seem a very real baby. The wise men who talked together and

pointed to the shining star overhead looked just like any of the great

nobles of Florence. And there at the back were the two horses looking on

with wise interested eyes, just as any of their own horses might have

done. Adoration of the Magi by

Giotto

It

seemed to make the story of Christmas a thing which had really happened,

instead of a far-away tale which had little meaning for them. Heaven and

the Madonna were not so far off after all. And it comforted them to

think that the Madonna had been a real woman like themselves, and that

the Jesu Bambino would stoop to bless them still, just as He leaned

forward to bless the wise men in the picture.

How

real too would seem the old story of the meeting of Anna and Joachim at

the Golden Gate, when they could gaze upon the two homely figures under

the narrow gateway. No visionary saints these,

but just a simple husband and wife, meeting each other with joy after a

sad separation, and yet with the touch of heavenly meaning shown by the

angel who hovers above and places a hand upon each head.

It

was not only in Florence that Giotto did his work. His fame spread far

and wide, and he went from town to town eagerly welcomed by all. We can

trace his footsteps as he went, by those wonderful old pictures which he

spread with loving care over the bare walls of the churches, lifting, as

it were, the curtain that hides Heaven from our view and bringing some

of its joys to earth.

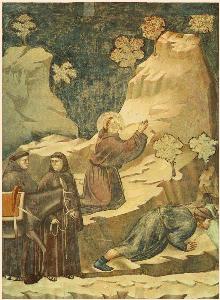

Then,

at Assisi, he covered the walls and ceiling of the church with the

wonderful frescoes of the life of St. Francis; and the little round

commonplace Arena Chapel of Padua is made exquisite inside by his

pictures of the life of our Lord. The Miracle of the Spring by

Giotto

In

the days when Giotto lived the towns of Italy were continually

quarrelling with one another, and there was always fighting going on

somewhere. The cities were built with a wall all round them, and the

gates were shut each night to keep out their enemies. But often the

fighting was between different families inside the city, and the grim

old palaces in the narrow streets were built tall and strong that they

might be the more easily defended.

In

the midst of all this war and quarrelling Giotto lived his quiet,

peaceful life, the friend of every one and the enemy of none. Rival

towns sent for him to paint their churches with his heavenly pictures,

and the people who hated Florence forgot that he was a Florentine. He

was just Giotto, and he belonged to them all. His brush was the white

flag of truce which made men forget their strife and angry passions, and

turned their thoughts to holier things.

Even

the great poet Dante did not scorn to be a friend of the peasant

painter, and we still have the portrait which Giotto painted of him in

an old fresco at Florence. Later on, when the great poet was a poor

unhappy exile, Giotto met him again at Padua and helped to cheer some of

those sad grey days, made so bitter by strife and injustice.

Now

when Giotto was beginning to grow famous, it happened that the Pope was

anxious to have the walls of the great Cathedral of St. Peter at Rome

decorated. So he sent messengers all over Italy to find out who were the

best painters, that he might invite them to come and do the work.

The

messengers went from town to town and asked every artist for a specimen

of his painting. This was gladly given, for it was counted a great

honour to help to make St. Peter's beautiful.

By

and by the messengers came to Giotto and told him their errand. The

Pope, they said, wished to see one of his drawings to judge if he was

fit for the great work. Giotto, who was always most courteous, `took a

sheet of paper and a pencil dipped in a red colour, then, resting his

elbow on his side, with one turn of the hand, he drew a circle so

perfect and exact that it was a marvel to behold.' `Here is your

drawing,' he said to the messenger, with a smile, handing him the

drawing.

`Am

I to have nothing more than this?' asked the man, staring at the red

circle in astonishment and disgust.

`That

is enough and to spare,' answered Giotto. `Send it with the rest.'

The

messengers thought this must all be a joke.

`How

foolish we shall look if we take only a round O to show his Holiness,'

they said.

But

they could get nothing else from Giotto, so they were obliged to be

content and to send it with the other drawings, taking care to explain

just how it was done.

The

Pope and his advisers looked carefully over all the drawings, and, when

they came to that round O, they knew that only a master-hand could have

made such a perfect circle without the help of a compass. Without a

moment's hesitation they decided that Giotto was the man they wanted,

and they at once invited him to come to Rome to decorate the cathedral

walls. So when the story was known the people became prouder than ever

of their great painter, and the round O of Giotto has become a proverb

to this day in Tuscany. Part of the Annunciation of

the Madonna by Giotto

`Round

as the O of Giotto, d' ye see; Which

means as well done as a thing can be.'

Later

on, when Giotto was at Naples, he was painting in the palace chapel one

very hot day, when the king came in to watch him at his work. It really

was almost too hot to move, and yet Giotto painted away busily.

`Giotto,'

said the king, `if I were in thy place I would give up painting for a

while and take my rest, now that it is so hot.'

`And,

indeed, so I would most certainly do,' answered Giotto, `if I were in

your place, your Majesty.'

It

was these quick answers and his merry smile that charmed every one, and

made the painter a favourite with rich and poor alike.

There

are a great many stories told of him, and they all show what a

sunny-tempered, kindly man he was.

It

is said that one day he was standing in one of the narrow streets of

Florence talking very earnestly to a friend, when a pig came running

down the road in a great hurry. It did not stop to look where it was

going, but ran right between the painter's legs and knocked him flat on

his back, putting an end to his learned talk.

Giotto

scrambled to his feet with a rueful smile, and shook his finger at the

pig which was fast disappearing in the distance.

`Ah,

well!' he said, `I suppose thou hadst as much right to the road as I

had. Besides, how many gold pieces I have earned by the help of thy

bristles, and never have I given any of thy family even a drop of soup

in payment.'

Another

time he went riding with a very learned lawyer into the country to look

after his property. For when Bondone died, he left all his fields and

his farm to his painter son. Very soon a storm came on, and the rain

poured down as if it never meant to stop.

`Let

us seek shelter in this farmhouse and borrow a cloak,' suggested Giotto.

So

they went in and borrowed two old cloaks from the farmer, and wrapped

themselves up from head to foot. Then they mounted their horses and rode

back together to Florence.

Presently

the lawyer turned to look at Giotto, and immediately burst into a loud

laugh. The rain was running from the painter's cap, he was splashed with

mud, and the old cloak made him look like a very forlorn beggar.

`Dost

think if any one met thee now, they would believe that thou art the best

painter in the world?' laughed the lawyer.

Giotto's

eyes twinkled as he looked at the funny figure riding beside him, for

the lawyer was very small, and had a crooked back, and rolled up in the

old cloak he looked like a bundle of rags.

`Yes!'

he answered quickly, `any one would certainly believe I was a great

painter, if he could but first persuade himself that thou dost know thy

A B C.'

In

all these stories we catch glimpses of the good- natured kindly painter,

with his love of jokes, and his own ready answers, and all the time we

must remember that he was filling the world with beauty, which it still

treasures to-day, helping to sow the seeds of that great tree of Art

which was to blossom so gloriously in later years.

And

when he had finished his earthly work it was in his own cathedral, `St.

Mary of the Flowers,' that they laid him to rest, while the people

mourned him as a good friend as well as a great painter. There he lies

in the shadow of his lily tower, whose slender grace and delicate-tinted

marbles keep his memory ever fresh in his beautiful city of Florence. The Lamentation by Giotto

Return to: Stories of the Italian Painters by Amy

Steedman