Candida Martinelli's Italophile Site

Main

Page This family-friendly site celebrates Italian culture for the enjoyment of children and

adults. Site-Overview

Knights of Art -

Michelangelo

Visit

my Angels in Italian Art Page

Visit

my Canaletto and Venice Art Page On-line images of art at Web

Gallery of Art: Sometimes

in a crowd of people one sees a tall man, who stands head and shoulders

higher than any one else, and who can look far over the heads of

ordinary- sized mortals. `What

a giant!' we exclaim, as we gaze up and see him towering above us. So

among the crowd of painters travelling along the road to Fame we see

above the rest a giant, a greater and more powerful genius than any that

came before or after him. When we hear the name of Michelangelo we

picture to ourselves a great rugged, powerful giant, a veritable son of

thunder, who, like the Titans of old, bent every force of Nature to his

will. Doni Tondo by Michelangelo This

Michelangelo was born at Caprese among the mountains of Casentino. His

father, Lodovico Buonarroti, was podesta or mayor of Caprese, and came

of a very ancient and honourable family, which had often distinguished

itself in the service of Florence. Now

the day on which the baby was born happened to be not only a Sunday, but

also a morning when the stars were especially favourable. So the wise

men declared that some heavenly virtue was sure to belong to a child

born at that particular time, and without hesitation Lodovico determined

to call his little son Michael Angelo, after the archangel Michael.

Surely that was a name splendid enough to adorn any great career. It

happened just then that Lodovico's year of office ended, and so he

returned with his wife and child to Florence. He had a property at

Settignano, a little village just outside the city, and there he settled

down. Most

of the people of the village were stone- cutters, and it was to the wife

of one of these labourers that little Michelangelo was sent to be

nursed. So in after years the great master often said that if his mind

was worth anything, he owed it to the clear pure mountain air in which

he was born, just as he owed his love of carving stone to the

unconscious influence of his nurse, the stone- cutter's wife. As

the boy grew up he clearly showed in what direction his interest lay. At

school he was something of a dunce at his lessons, but let him but have

a pencil and paper and his mind was wide awake at once. Every spare

moment he spent making sketches on the walls of his father's house. But

Lodovico would not hear of the boy becoming an artist. There were many

children to provide for, and the family was not rich. It would be much

more fitting that Michelangelo should go into the silk and woollen

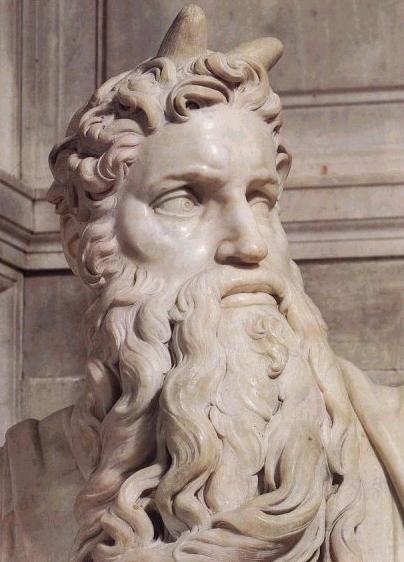

business and learn to make money. Moses (detail) by Michelangelo But

it was all in vain to try to make the boy see the wisdom of all this.

Scold as they might, he cared for nothing but his pencil, and even after

he was severely beaten he would creep back to his

beloved work. How he envied his friend Francesco who worked in

the shop of Master Ghirlandaio! It was a joy even to sit and listen to

the tales of the studio, and it was a happy day when Francesco brought

some of the master's drawings to show to his eager friend. Little

by little Lodovico began to see that there was nothing for it but to

give way to the boy's wishes, and so at last, when he was fourteen years

old, Michelangelo was sent to study as a pupil in the studio of Master

Ghirlandaio. It

was just at the time when Ghirlandaio was painting the frescoes of the

chapel in Santa Maria Novella, and Michelangelo learned many lessons as

he watched the master at work, or even helped with the less important

parts. But

it was like placing an eagle in a hawk's nest. The young eagle quickly

learned to soar far higher than the hawk could do, and ere long began to

`sweep the skies alone.' It

was not pleasant for the great Florentine master, whose work all men

admired, to have his drawings corrected by a young lad, and perhaps

Michelangelo was not as humble as he should have been. In the strength

of his great knowledge he would sometimes say sharp and scornful things,

and perhaps he forgot the respect due from pupil to master. Be

that as it may, he left Ghirlandaio's studio when he was sixteen years

old, and never had another master. Thenceforward he worked out his own

ideas in his giant strength, and was the pupil of none. The

boy Francesco was still his friend, and together they went to study in

the gardens of San Marco, where Lorenzo the Magnificent had collected

many statues and works of art. Here was a new field for Michelangelo.

Without needing a lesson he began to copy the statues in terra-cotta,

and so clever was his work that Lorenzo was delighted with it. `See,

now, what thou canst do with marble,' he said. `Terra-cotta is but poor

stuff to work in.' Michelangelo

had never handled a chisel before, but he chipped and cut away the

marble so marvellously that life seemed to spring out of the stone.

There was a marble head of an old faun in the garden, and this

Michelangelo set himself to copy. Such a wonderful copy did he make that

Lorenzo was amazed. It was even better than the original, for the boy

had introduced ideas of his own and had made the laughing mouth a little

open to show the teeth and the tongue of the faun. Lorenzo noticed this,

and turned with a smile to the young artist. `Thou

shouldst have remembered that old folks never keep all their teeth, but

that some of them are always wanting,' he said. Of

course Lorenzo meant this as a joke, but Michelangelo immediately took

his hammer and struck out several of the teeth, and this too pleased

Lorenzo greatly. There

was nothing that the Magnificent ruler loved so much as genius, so

Michelangelo was received into the palace and made the companion of

Lorenzo's sons. Not only did good fortune thus smile upon the young artist, but to his great astonishment Lodovico too found

that benefits were showered upon him, all for the sake of his famous

young son. These

years of peace, and calm, steady work had the greatest effect on

Michelangelo's work, and he learned much from the clever, brilliant men

who thronged Lorenzo's court. Then, too, he first listened to that

ringing voice which strove to raise Florence to a sense of her sins,

when Savonarola preached his great sermons in the Duomo. That teaching

sank deep into the heart of Michelangelo, and years afterwards he left

on the walls of the Sistine Chapel a living echo of those thundering

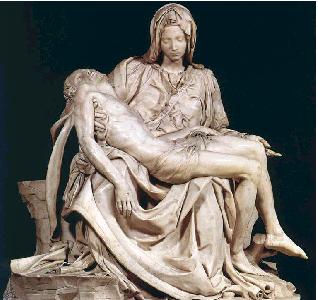

words. The Pieta by Michelangelo Like

all the other artists, he would often go to study Masaccio's frescoes in

the little chapel of the Carmine. There was quite a band of young

artists working there, and very soon they began to look with envious

feelings at Michelangelo's drawings, and their jealousy grew as his fame

increased. At last, one day, a youth called Torriggiano could bear it no

longer, and began to make scornful remarks, and worked himself up into

such a rage that he aimed a blow at Michelangelo with his fist, which

not only broke his nose but crushed it in such a way that he was marked

for life. He had had a rough, rugged look before this, but now the

crooked nose gave him almost a savage expression which he never lost. Changes

followed fast after this time of quiet. Lorenzo the Magnificent died,

and his son, the weak Piero de Medici, tried to take his place as ruler

of Florence. For a time Michelangelo continued to live

at the court of Piero, but it was not encouraging to work for a

master whose foolish taste demanded statues to be made out of snow,

which, of course, melted at the first breath of spring. Michelangelo

never forgot all that he owed to Lorenzo, and he loved the Medici

family, but his sense of justice made him unable to take their part when

trouble arose between them and the Florentine people. So when the

struggle began he left Florence and went first to Venice and then to

Bologna. From afar he heard how the weak Piero had been driven out of

the city, but more bitter still was his grief when the news came that

the solemn warning voice of the great preacher Savonarola was silenced

for ever. Then

a great longing to see his beloved city again filled his heart, and he

returned to Florence. Botticelli

was a sad, broken-down old man now, and Ghirlandaio was also growing

old, but Florence was still rich in great artists. Leonardo da Vinci,

Perugino, and Filippino Lippi were all there, and men talked of the

coming of an even greater genius, the young Raphael of Urbino. There

happened just then to be at the works of the Cathedral of St. Mary of

the Flowers a huge block of marble which no one knew how to use.

Leonardo da Vinci had been invited to carve a statue out of it, but he

had refused to try, saying he could do nothing with it. But when the

marble was offered to Michelangelo his eye kindled and he stood for a

long time silent before the great white block. Through the outer walls

of stone he seemed to see the figure imprisoned in the marble, and his giant strength and giant mind

longed to go to work to set that figure free. And

when the last covering of marble was chipped and cut away there stood

out a magnificent figure of the young David. Perhaps he is too strong

and powerful for our idea of the gentle shepherd-lad, but he is a

wonderful figure, and Goliath might well have trembled to meet such a

young giant.

David

(detail) by Michelangelo People

flocked to see the great statue, and many were the discussions as to

where it should be placed. Artists were never tired of giving their

opinion, and even of criticising the work. `It seems to me,' said one,

`that the nose is surely much too large for the face. Could you not

alter that?' Michelangelo

said nothing, but he mounted the scaffolding and pretended to chip away

at the nose with his chisel. Meanwhile he let drop some marble chips and

dust upon the head of the critic beneath. Then he came down. `Is

that better?' he asked gravely. `Admirable!'

answered the artist. `You have given it life.' Michelangelo

smiled to himself. How wise people thought themselves when they often

knew nothing about what they were talking! But the critic was satisfied,

and did not notice the smile. It

would fill a book to tell of all the work which Michelangelo did; but

although he began so much, a great deal of it was left unfinished. If he

had lived in quieter times, his work would have been more complete; but

one after another his patrons died, or changed their minds, and set him

to work at something else before he had finished what he was doing. The

great tomb which Pope Julius had ordered him to make was never finished,

although Michelangelo drew out all the designs for it, and for forty

years was constantly trying to complete it. The Pope began to think it

was an evil omen to build his own tomb, so he made up his mind that

Michelangelo should instead set to work to fresco the ceiling of the

Sistine Chapel. In vain did the great sculptor repeat that he knew but

little of the art of painting. `Didst

thou not learn to mix colours in the studio of Master Ghirlandaio?' said

Julius. `Thou hast but to remember the lessons he taught thee. And,

besides, I have heard of a great drawing of a battle- scene which thou

didst make for the Florentines, and have seen many drawings of thine,

one especially: a terrible head of a furious old man, shrieking in his

rage, such as no other hand than thine could have drawn. Is there aught

that thou canst not do if thou hast but the will?' And

the Pope was right; for as soon as Michelangelo really made up his mind

to do the work, all difficulties seemed to vanish. It

was no easy task he had undertaken. To stand upright and cover vast

walls with painting is difficult enough, but Michelangelo was obliged to

lie flat upon a scaffolding and paint the ceiling above him. Even to

look up at that ceiling for ten minutes makes the head and neck ache

with pain, and we wonder how such a piece of work could ever have been

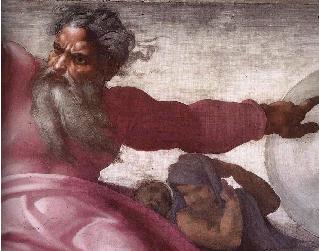

done. Creation of Sun, Moon, Planets

from Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo No

help would the master accept, and he had no pupils. Alone he worked, and

he could not bear to have any one near him looking on. In silence and

solitude he lay there painting those marvellous frescoes of the story of

the Creation to the time of Noah. Only Pope Julius himself dared to

disturb the master, and he alone climbed the scaffolding and watched the

work. `When

wilt thou have finished?' was his constant cry. `I long to show thy work

to the world.' `Patience,

patience,' said Michelangelo. `Nothing is ready yet.' `But

when wilt thou make an end?' asked the impatient old man. `When

I can,' answered the painter. Then

the Pope lost his temper, for he was not accustomed to be answered like

this. God as he gives life to Adam

from the Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo `Dost

thou want to be thrown head first from the scaffold?' he asked angrily.

`I tell thee that will happen if the work is not finished at once.' So,

incomplete as they were, Michelangelo was obliged to uncover the

frescoes that all Rome might see them. It was many years before the

ceiling was finished or the final fresco of the Last Judgment painted

upon the end wall. Michelangelo

lived to be a very old man, and his life was lonely and solitary to the

end. The one woman he loved, Vittoria Colonna, had died, and with her

death all brightness for him had faded. Although he worked so much in

Rome, it was always Florence that he loved. There it was that he began

the statues for the Chapel of the Medici, and there, too, he helped to

build the defences of San Miniato when the Medici family made war upon

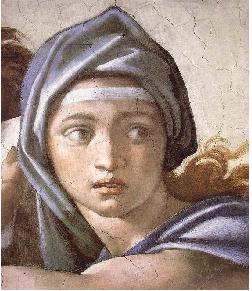

the City of Flowers. Delphic Sibyl from Sistine

Chapel by Michelangelo

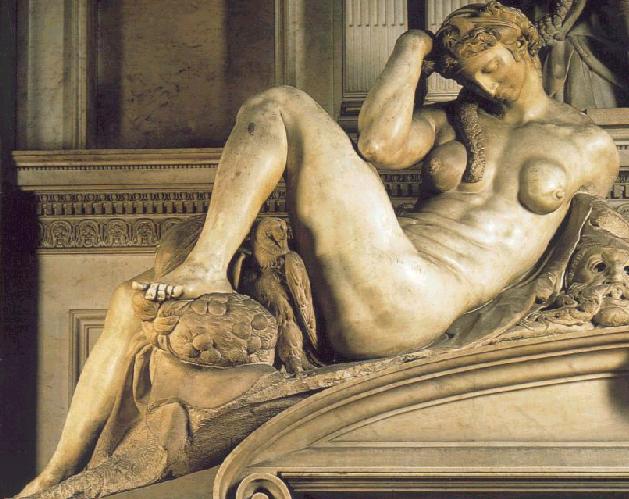

Part of the Medici Tomb, Florence Urbino from the Medici Tomb, Florence Night from the Medici Tomb, Florence Dawn from Medici Tomb, Florence Twilight from Medici Tomb, Florence Day from Medici Tomb, Florence

Return to:

Stories of the Italian Painters

by Amy Steedman