Candida Martinelli's Italophile Site

Main

Page This family-friendly site celebrates Italian culture for the enjoyment of children and

adults. Site-Overview

Knights of Art -

Pietro Perugino

Visit

my Angels in Italian Art Page

Visit

my Canaletto and Venice Art Page On-line images of art at Web

Gallery of Art: It

was early morning, and the rays of the rising sun had scarcely yet

caught the roofs of the city of Perugia, when along the winding road

which led across the plain a man and a boy walked with steady,

purposelike steps towards the town which crowned the hill in front. The

man was poorly dressed in the common rough clothes of an Umbrian

peasant. Hard work and poverty had bent his shoulders and drawn stern

lines upon his face, but there was a dignity about him which marked him

as something above the common working man. The

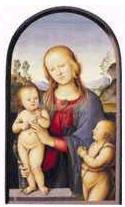

Virgin and the Child (detail) by Perugino The

little boy who trotted barefoot along by the side of his father had a

sweet, serious little face, but he looked tired and hungry, and scarcely

fit for such a long rough walk. They had started from their home at

Castello delle Pieve very early that morning, and the piece of black

bread which had served them for breakfast had been but small. Away in

front stretched that long, white, never-ending road; and the little

dusty feet that pattered so bravely along had to take hurried runs now

and again to keep up with the long strides of the man, while the wistful

eyes, which were fixed on that distant town, seemed to wonder if they

would really ever reach their journey's end. `Art

tired already, Pietro?' asked the father at length, hearing a panting

little sigh at his side. `Why, we are not yet half-way there! Thou must

step bravely out and be a man, for to-day thou shalt begin to work for

thy living, and no longer live the life of an idle child.' The

boy squared his shoulders, and his eyes shone. `It

is not I who am tired, my father,' he said. `It is only that my legs

cannot take such good long steps as thine; and walk as we will the road

ever seems to unwind itself further and further in front, like the magic

white thread which has no end.' The

father laughed, and patted the child's head kindly. `The

end will come ere long,' he said. `See where the mist lies at the foot

of the hill; there we will begin to climb among the olive-trees and

leave the dusty road. I know a quicker way by which we may reach the

city. We will climb over the great stones that mark the track of the

stream, and before the sun grows too hot we will have reached the city

gates.' It

was a great relief to the little hot, tired feet to feel the cool grass

beneath them, and to leave the dusty road. The boy almost forgot his

tiredness as he scrambled from stone to stone, and filled his hands with

the violets which grew thickly on the banks, scenting the morning air

with their sweetness. And when at last they came out once more upon the

great white road before the city gates, there was so much to gaze upon

and wonder at, that there was no room for thoughts of weariness or

hunger. There

stood the herds of great white oxen, patiently waiting to pass in.

Pietro wondered if their huge wide horns would not reach from side to

side of the narrow street within the gates. There the shepherd-boys

played sweet airs upon their pipes as they walked before their flocks,

and led the silly frightened sheep out of the way of passing carts.

Women with bright-coloured handkerchiefs tied over their heads crowded

round, carrying baskets of fruit and vegetables from the country round.

Carts full of scarlet and yellow pumpkins were driven noisily along.

Whips cracked, people shouted and talked as much with their hands as

with their lips, and all were eager to pass through the great Etruscan

gateway, which stood grim and tall against the blue of the summer sky.

Much good service had that gateway seen, and it was as strong as when it

had been first built hundreds of years before, and was still able to

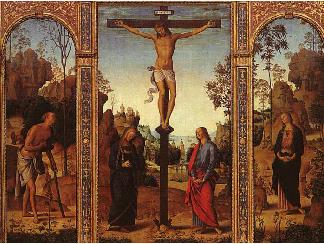

shut out an army of enemies, if Perugia had need to defend herself. The Crucifixion by Perugino Pietro

and his father quickly threaded their way through the crowd, and passed

through the gateway into the steep narrow street beyond. It was cool and

quiet here. The sun was shut out by the tall houses, and the shadows lay

so deep that one might have thought it was the hour of twilight, but for

the peep of bright blue sky which showed between the overhanging eaves

above. Presently they reached the great square market-place, where all

again was sunshine and bustle, with people shouting and selling their

wares, which they spread out on the ground up to the very steps of the

cathedral and all along in

front of the Palazzo Publico. Here the man stopped, and asked one of the

passers-by if he could direct him to the shop of Niccolo the painter. `Yonder

he dwells,' answered the citizen, and pointed to a humble shop at the

corner of the market-place. `Hast thou brought the child to be a model?' Pietro

held his head up proudly, and answered quickly for himself. `I

am no longer a child,' he said; `and I have come to work and not to sit

idle.' The

man laughed and went his way, while father and son hurried on towards

the little shop and entered the door. The

old painter was busy, and they had to wait a while until he could leave

his work and come to see what they might want. `This

is the boy of whom I spoke,' said the father as he pushed Pietro forward

by his shoulder. `He is not well grown, but he is strong, and has learnt

to endure hardness. I promise thee that he will serve thee well if thou

wilt take him as thy servant.' St. Augustine (detail) by

Perugino The

painter smiled down at the little eager face which was waiting so

anxiously for his answer. `What

canst thou do?' he asked the boy. `Everything,'

answered Pietro promptly. `I can sweep out thy shop and cook thy dinner.

I will learn to grind thy colours and wash thy brushes, and do a man's

work.' `In

faith,' laughed the painter, `if thou canst do everything, being yet so

young, thou wilt soon be the greatest man in Perugia, and bring great

fame to this fair city. Then will we call thee no longer Pietro Vanucci,

but thou shalt take the city's name, and we will call thee Perugino.' The

master spoke in jest, but as time went on and he watched the boy at

work, he marvelled at the quickness with which the child learned to

perform his new duties, and began to think the jest might one day turn

to earnest. From

early morning until sundown Pietro was never idle, and when the rough

work was done he would stand and watch the master as he painted, and

listen breathless to the tales which Niccolo loved to tell. `There

is nothing so great in all the world as the art of painting,' the master

would say. `It is the ladder that leads up to heaven, the window which

lets light into the soul. A painter need never be lonely or poor. He can

create the faces he loves, while all the riches of light and colour and

beauty are always his. If thou hast it in thee to be a painter, my

little Perugino, I can wish thee no greater fortune.' Then

when the day's work was done and the short spell of twilight drew near,

the boy would leave the shop and run swiftly down the narrow street

until he came to the grim old city gates. Once outside, under the wide

blue sky in the free open air of the country, he drew a long, long

breath of pleasure, and quickly found a hidden corner in the cleft of

the hoary trunk of an olive-tree, where no passer-by could see him.

There he sat, his chin resting on his hands, gazing and gazing out over the plain

below, drinking in the beauty with his hungry eyes. How

he loved that great open space of sweet fresh air, in the calm pure

light of the evening hour. That white light, which seemed to belong more

to heaven than to earth, shone on everything around. Away in the

distance the purple hills faded into the sunset sky. At his feet the

plain stretched away, away until it met the mountains, here and there

lifting itself in some little hill crowned by a lonely town whose roofs

just caught the rays of the setting sun. The evening mist lay like a

gossamer veil upon the low-lying lands, and between the little towns the

long straight road could be seen, winding like a white ribbon through

the grey and silver, and marked here and there by a dark cypress-tree or

a tall poplar. And always there would be a glint of blue, where a stream

or river caught the reflection of the sky and held it lovingly there,

like a mirror among the rocks. St. Michael by Perugino But

Pietro did not have much time for idle dreaming. His was not an easy

life, for Niccolo made but little money with his painting, and the boy

had to do all the work of the house besides attending to the shop. But

all the time he was sweeping and dusting he looked forward to the happy

days to come when he might paint pictures and become a famous artist. Whenever

a visitor came to the shop, Pietro would listen eagerly to his talk and

try to learn something of the great world of Art. Sometimes he

would even venture to ask questions, if the stranger happened to

be one who had travelled from afar. `Where

are the most beautiful pictures to be found?' he asked one day when a

Florentine painter had come to the little shop and had been describing

the glories he had seen in other cities. `And where is it that the

greatest painters dwell?' `That

is an easy question to answer, my boy,' said the painter. `All that is

fairest is to be found in Florence, the most beautiful city in all the

world, the City of Flowers. There one may find the best of everything,

but above all, the most beautiful pictures and the greatest of painters.

For no one there can bear to do only the second best, and a man must

attain to the very highest before the Florentines will call him great.

The walls of the churches and monasteries are covered with pictures of

saints and angels, and their beauty no words can describe.' `I

too will go to Florence, said Pietro to himself, and every day he longed

more and more to see that wonderful city. It

was no use to wait until he should have saved enough money to take him

there. He scarcely earned enough to live on from day to day. So at last,

poor as he was, he started off early one morning and said good-bye to

his old master and the hard work of the little shop in Perugia. On he

went down the same long white road which had seemed so endless to him

that day when, as a little child, he first came to Perugia. Even now,

when he was a strong young man, the way seemed long and weary across

that great plain, and he was often foot- sore and discouraged. Day after

day he travelled on, past the great lake which lay like a sapphire in

the bosom of the plain, past many towns and little villages, until at

last he came in sight of the City of Flowers. It

was a wonderful moment to Perugino, and he held his breath as he looked.

He had passed the brow of the hill, and stood beside a little stream

bordered by a row of tall, straight poplars which showed silvery white

against the blue sky. Beyond, nestling at the foot of the encircling

hills, lay the city of his dreams. Towers and palaces, a crowding

together of pale red sunbaked roofs, with the great dome of the

cathedral in the midst, and the silver thread of the Arno winding its

way between--all this he saw, but he saw more than this. For it seemed

to him that the Spirit of Beauty hovered above the fair city, and he

almost heard the rustle of her wings and caught a glimpse of her

rainbow-tinted robe in the light of the evening sky. Poor

Pietro! Here was the world he longed to conquer, but he was only a poor

country boy, and how was he to begin to climb that golden ladder of Art

which led men to fame and glory? Vallombroso Altar (detail) by

Perugino Well,

he could work, and that was always a beginning. The struggle was hard,

and for many a month he often went hungry and had not even a bed to lie

on at night, but curled himself up on a hard wooden chest. Then good

fortune began to smile upon him. The

Florentine artists to whose studios he went began to notice the

hardworking boy, and when they

looked at his work, with all its faults and want of finish, they saw in

it that divine something called genius which no one can mistake. Then

the doors of another world seemed to open to Pietro. All day long he

could now work at his beloved painting and learn fresh wonders as he

watched the great men use the brush and pencil. In the studio of the

painter Verocchio he met the men of whose fame he had so often heard,

and whose work he looked upon with awe and reverence. There

was the good-tempered monk of the Carmine, Fra Filipo Lippi, the young

Botticelli, and a youth just his own age whom they called Leonardo da

Vinci, of whom it was whispered already that he would some day be the

greatest master of the age.

These

were golden days for Perugino, as he was called, for the name of the

city where he had come from was always now given to him. The pictures he

had longed to paint grew beneath his hand, and upon his canvas began to

dawn the solemn dignity and open-air spaciousness of those evening

visions he had seen when he gazed across the Umbrian Plain. There was no

noise of battle, no human passion in his pictures. His saints stood

quiet and solemn, single figures with just a thread of interest binding

them together, and always beyond was the great wide open world, with the

white light shining in the sky, the blue thread of the river, and the

single trees pointing upwards--dark, solemn cypress, or feathery larch

or poplar. There

was much for the young painter still to learn, and perhaps he learned

most from the silent teaching of that little dark chapel of the Carmine,

where Masaccio taught more wonderful lessons by his frescoes than any

living artist could teach. Then

came the crowning honour when Perugino received an invitation from the

Pope to go to Rome and paint the walls of the Sistine Chapel. Hence

forth it was a different kind of life for the young painter. No need to

wonder where he would get his next meal, no hard rough wooden chest on

which to rest his weary limbs when the day's work was done. Now he was

royally entertained and softly lodged, and men counted it an honour to

be in his company. But

though he loved Florence and was proud to do his painting in Rome, his

heart ever drew him back to the city on the hill whose name he bore. Virgin and Child by Perugino Again

he travelled along the winding road, and his heart beat fast as he drew

nearer and saw the familiar towers and roofs of Perugia. How well he

remembered that long-ago day when the cool touch of the grass was so

grateful to his little tired dusty feet! He stooped again to fill his

hands with the sweet violets, and thought them sweeter than all the fame

and fair show of the gay cities. And

as he passed through the ancient gateway and threaded his way up the

narrow street towards the little shop, he seemed to see once more the

kindly smile of his old master and to hear him say, `Thou wilt soon be

the greatest man in Perugia, and we will call thee no longer Pietro

Vanucci, but Perugino.' So

it had come to pass. Here he was. No longer a little ragged, hungry boy,

but a man whom all delighted to honour. Truly this was a world of

changes! A

bigger studio was needed than the little old shop, for now he had more

pictures to paint than he well knew how to finish. Then, too, he had

many pupils, for all were eager to enter the studio of the great master.

There it was that one morning a new pupil was brought to him, a boy of

twelve, whose guardians begged that Perugino would teach and train him. Perugino

looked with interest at the child. Seldom had he seen such a beautiful

oval face, framed by such soft brown curls--a face so pure and lovable

that even at first sight it drew out love from the hearts of those who

looked at him. `His

father was also a painter,' said the guardian, `and Raphael, here, has

caught the trick of using his pencil and brush, so we would have him

learn of the greatest master in the land.' After

some talk, the boy was left in the studio at Perugia, and day by day

Perugino grew to love him more. It was not only that little Raphael was

clever and skilful, though that alone often made the master marvel. `He

is my pupil now, but some day he will be my master, and I shall learn of

him,' Perugino would often say as he watched the boy at work. But more

than all, the pure sweet nature and the polished gentleness of his

manners charmed the heart of the master, and he loved to have the boy

always near him, and to teach him was his greatest pleasure. Those

quiet days in the Perugia studio never lasted very long. From all

quarters came calls to Perugino, and, much as he loved work, he could

not finish all that was wanted. It

happened once when he was in Florence that a certain prior begged him to

come and fresco the walls of his convent. This prior was very famous for

making a most beautiful and expensive blue colour which he was anxious

should be used in the painting of the convent walls. He was a mean,

suspicious man, and would not trust Perugino with the precious blue

colour, but always held it in his own hands and grudgingly doled it out

in small quantities, torn between the desire to have the colour on his

walls and his dislike to parting with anything so precious. As

Perugino noted this, he grew angry and determined to punish the prior's

meanness. The next time therefore that there was a blue sky to be

painted, he put at his side a large bowl of fresh water, and then called

on the prior to put out a small quantity of the blue colour in a little

vase. Each time he dipped his brush into the vase, Perugino washed it

out with a swirl in the bowl at his side, so that most of the colour was

left in the water, and very little was put on to the picture. Virgin and Child and Saints by

Perugino `I

pray thee fill the vase again with blue,' he said carelessly when the

colour was all gone. The prior groaned aloud, and turned grudgingly to

his little bag. `Oh

what a quantity of blue is swallowed up by this plaster!' he said, as he

gazed at the white wall, which scarcely showed a trace of the precious

colour. `Yes,'

said Perugino cheerfully, `thou canst see thyself how it goes.' Then

afterwards, when the prior had sadly gone off with his little empty bag,

Perugino carefully poured the water from the bowl and gathered together

the grains of colour which had sunk to the bottom. `Here

is something that belongs to thee,' he said sternly to the astonished

prior. `I would have thee learn to trust honest men and not treat them

as thieves. For with all thy suspicious care, it was easy to rob thee if

I had had a mind.' During

all these years in which Perugino had worked so diligently, the art of

painting had been growing rapidly. Many of the new artists shook off the

old rules and ideas, and began to paint in quite a new way. There was

one man especially, called Michelangelo, whose story you will hear later

on, who arose like a giant, and with his new way and greater knowledge

swept everything before him. Perugino

was jealous of all these new ideas, and clung more closely than ever to

his old ideals, his quiet, dignified saints, and spacious landscapes. He

talked openly of his dislike of the new style, and once he had a serious

quarrel with the great Michelangelo. There

was a gathering of painters in Perugino's studio that day. Filippino

Lippi, Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, and Leonardo were there, and in the

background the pupil Raphael was listening to the talk. `What

dost thou think of this new style of painting?' asked Botticelli. `To me

it seems but strange and unpleasing. Music and motion are delightful,

but this violent twisting of limbs to show the muscles offends my

taste.' `Yet

it is most marvellously skilful,' said the young Leonardo thoughtfully. `But

totally unfit for the proper picturing of saints and the blessed

Madonna,' said Filippino, shaking his curly head. `I

never trouble myself about it,' said Ghirlandaio. `Life is too short to

attend to other men's work. It takes all my care and attention to look

after mine own. But see, here comes the great Michelangelo himself to

listen to our criticism.' The

curious, rugged face of the great artist looked good-naturedly on the

company, but his strong knotted hands waved aside their greetings. `So

you were busy as usual finding fault with my work,' he said. `Come,

friend Perugino, tell me what thou hast found to grumble at.' `I

like not thy methods, and that I tell thee frankly,' answered Perugino,

an angry light shining in his eyes. `It is such work as thine that drags

the art of painting down from the heights of heavenly things to the low

taste of earth. It robs it of all dignity and restfulness, and destroys

the precious traditions handed down to us since the days of Giotto.'

Christ Give Keys to St. Peter

by Perugino The

face of Michelangelo grew angry and scornful as he listened to this. `Thou

art but a dolt and a blockhead in Art,' he said. `Thou wilt soon see

that the day of thy saints and Madonnas is past, and wilt cease to paint

them over and over again in the same manner, as a child doth his lesson

in a copy book.' Then

he turned and went out of the studio before any one had time to answer

him. Perugino

was furiously angry and would not listen to reason, but must needs go

before the great Council and demand that they should punish Michelangelo

for his hard words. This of course the Council refused to do, and

Perugino left Florence for Perugia, angry and sore at heart. It

seemed hard, after all his struggles and great successes, that as he

grew old people should begin to tire of his work, which they had once

thought so perfect. But

if the outside world was sometimes disappointing, he had always his home

to turn to, and his beautiful wife Chiare. He had married her in his

beloved Perugia, and she meant all the joy of life to him. He was so

proud of her beauty that he would buy her the richest dresses and most

costly jewels, and with his own hands would deck her with them. Her

brown eyes were like the depths of some quiet pool, her fair face and

the wonderful soul that shone there were to him the most perfect picture

in the world. `I

will paint thee once, that the world may be the richer,' said Perugino,

`but only once, for thy beauty is too rare for common use. And I will

paint thee not as an earthly beauty, but thou shalt be the angel in the

story of Tobias which thou knowest.' So

he painted her as he said. And in our own National Gallery we still have

the picture, and we may see her there as the beautiful angel who leads

the little boy Tobias by the hand. Tobias and the Saint by

Perugino Up

to the very last years of his life, Perugino painted as diligently as he

had ever done, but the peaceful days of Perugia had long since given

place to war and tumult, both within and without the city. Then too a

terrible plague swept over the countryside, and people died by

thousands. To

the hospital of Fartignano, close to Perugia, they carried Perugino when

the deadly plague seized him, and there he died. There was no time to

think of grand funerals; the people were buried as quickly as possible,

in whatever place lay closest at hand. So

it came to pass that Perugino was laid to rest in an open field under an

oak-tree close by. Later on his sons wished to have him buried in holy

ground, and some say that this was done, but nothing is known for

certain. Perhaps if he could have chosen, he would have been glad to

think that his body should rest under the shelter of the trees he loved

to paint, in that waste openness of space which had always been his

vision of beauty, since, as a little boy, he gazed across the Umbrian

Plain, and the wonder of it sank into his soul.

Return to:

Stories of the Italian Painters

by Amy Steedman