Below are more goodies about barometer makers, modern London and old London...

Candida Martinelli's Italophile Site

Main

Page This family-friendly site celebrates Italian culture for the enjoyment of children and

adults. Site-Overview

There were immigrants from Italy

from 1000 onward, and possibly earlier: artists, artisans and

musicians from Italy traveled around Europe and further, offering

their services to the wealthy, or performing for the public,

including in London. In the 1200s and

1300s, bankers, traders, and merchants of all kinds, mainly from the

Genoa, Veneto and Lombardy regions, rich trading regions, set up

offices in major trading cities and along trade routes, including in

London. In the late 1500s, the Venetian Giacomo Verelini was making glass in

London. After his death, British businessmen monopolized

glass-making in Britain, but imported Venetian glass makers to run the

show. This is a

link to an article on the Vauxhall Society site about this. In the 1700s and 1800s, Italian artisans/craftsmen emigrated with

their skills, to find a more secure life, to the capital cities of

Europe, and to the emerging industrial cities of Britain, including

London, a growing megalopolis that grew in population from 1

million in 1800, to 6,7 million in 1900. Here is some information on the Italians living in London from the 1700s to 1911

as described in

an informative book, in Italian, on Google Books:

Arrivi by the Italia Comitato Nazionale Italia nel Mondo.

This is a summary of the

paragraph about the London Italians on page 210: The Italian community

in London was based in the area of the north of the city,

Clerkenwell, by the mid 1700s. In the beginning, they

were mainly artisans making mirrors, frames, mosaics, and

scientific instruments like barometers, thermometers,

microscopes, telescopes and surgical instruments.

Over time, rural

immigrants joined the group, although many of these were

seasonal immigrants. Other arrivals, later,

were republicans fleeing a monarchist Italy, and members of the

rare middle class from all over Italy. By the beginning of the

1800s, the Little Italy of Clerkenwell already had a Catholic

church, and was the most stable community of foreigners living

in London at that time. In the 1600s, Italian craftsmen were making mirrors

(a looking-glass, uno specchio) such as this.

On page 346, they talk

about Italians in London and Britain at a later period 1830s-early

1900s: In the years from 1841

to 1881 the residents of the London Italian quarter of Holborn

were mainly frame makers, statue makers, ice cream makers, and

organists. Only in the latter

period did builders arrive. (They explain a bit earlier that

most of the British needs for manual laborers was filled by Irish immigrants.) At the top of the

Italian labor pyramid were the artisans made up of makers of

optical instruments, silversmiths, makers of frames, bird-cages

and fine wood workers. From 1861 to 1911 in

Britain, the major part of Italians worked in food service jobs,

restaurants, as cooks and waiters. The numbers grew rapidly

from 1891 to 1911 going from less than 1000 to more than 4000

people. The second largest

group were the grocery shop workers, followed closely by

domestic workers (maids, grooms, etc.). Other categories were

street-vendors, ice cream sellers, roast meat sellers, and

organists. An Anglo-Italian ice-cream barrowman London was home to immigrants by the name of

Martinelli. They were not part of the huge wave of

immigrants that spread out from Italy during the late

1800s to early 1900s. They probably left Italy around

1800, from the Lake Como area. One of the earliest Martinelli immigrants to

London was part of the artisan/craftsmen

community (wood workers, metal workers, instrument makers, mirror

and frame makers) who found it easiest to emigrate from the Italian

peninsula to various European capitals. They took their

valuable skills and left for a more secure life abroad. Today

we would call it a 'brain-drain', or a 'skills-drain', I suppose. From the Arrivi book I learned

on page 338: From regions around

Lake Como, immigrants went to German cities, the Veneto, and to

Torino. These immigrants were

those who had the most common skills of immigrants at that

time: sellers of barometers and thermometers, metal workers and

many builders and craftsmen. An Italian frame from the 1800s, gilded wood

Louis (or Luigi) Martinelli, born probably circa 1766, in or

near Como, Italy,

was likely one of those Lake Como

barometer, thermometer, mirror and frame makers. He worked in London in the

first half of the

1800s and died in 1845, in London. He and his family carried on the

barometer

crafting trade for nearly 100 years in London, under various names,

and at various addresses.

Gondolier on Lake Como Barometers measure air-pressure, which can

then be used to predict the weather. They can also be used to

determine altitude: the height of the mercury in it's tube in

the barometer corresponds to a table showing the feet above sea

level. Barometer Face (Aneroid)

Barometers were the must-have, high-tech item

of their day, first in the homes of the wealthy, at at shipping and

fishing ports, and then in the

homes of the growing middle class. From the mid 1800s to 1900, mercury barometers

reigned, but then the aneroid barometer made it possible to produce

smaller barometers, more cheaply, eventually destroying the market

for expensive handcrafted mercury barometers. At it's height, the barometer was combined in a

beautifully tooled wooden case with various other instruments like a clock, a spirit level, a mirror, a

thermometer, and a hygrometer, which measures relative humidity.

The early instrument makers called themselves 'makers of philosophical

instruments'.

The Italian White Pages show that Martinellis still live in the Lake

Como area, but because of Italy's massive internal migration,

Martinellis live everywhere in Italy, from Lake Como to Sicily!

So it is not definite that all the Martinellis making barometers in

London were related. There are many Martinellis who made barometers in

London over the years. Some may have been itinerant, coming to

Britain, then returning to Italy for a while, before returning again to

London. This was a common pattern, it seems, for many immigrants. I am not going to trace

all of them, but I will use some of Lewis Martinelli's London family history,

all accessible from public records, to help illuminate the life of Anglo-Italians in London from

roughly 1800 to 1900. Lewis Martinelli was born in or

near Como, Lombardy, Italy, in 1766. Because he was a barometer

maker, some of his movements can be traced from the signatures on his

barometers.

For example, from a barometer signature database

compiled for scientific instrument collectors, we know that: Lewis

Martinelli made wheel barometers and thermometers, and was also a

carver, gilder and print seller at 82 Leather Lane, London from 1803 to

1811. Leather Lane was at the center of London's

Italian community since the 1700s, and would remain so until World War

I. Leather Lane links the main roads of High Holborn and Clerkenwell Road.

Clerkenwell is London's original

Little Italy, beginning around 1700, and later Holborn became known for the large number of

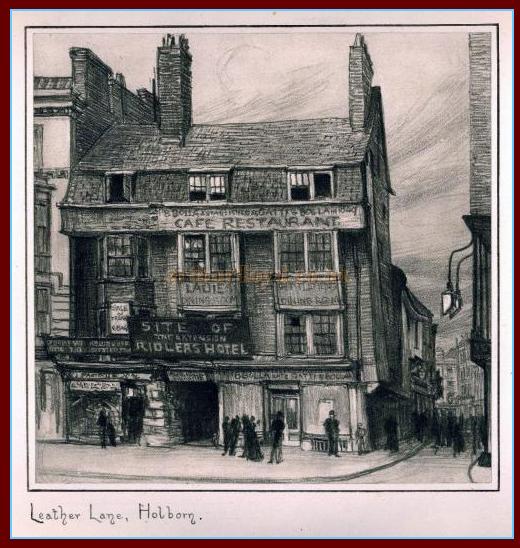

Italians and Anglo-Italians living there. Here is a view of old Leather

Lane looking toward High Holborn

Leather Lane, today, is known for the

Leather Lane outdoor market where the stalls line the street.

(There is a very short

promo for the

market on YouTube.)

The market has been a fixture of the area since as long as anyone can

remember, 300 years, say the London historians.

Leather Lane is a very old London street, mentioned in a 1538

survey of London. In the early 1700s, a large brewery covered

the end of Leather Lane. By the end of the 1700s and the early part

of the 1800s, there were several clockmakers on the street.

And there was a renowned coach maker, William Fenton, at 36 Leather

Lane during this same period. But there were also churches,

printers, inns, pubs... all sorts of businesses on the street over the

years. And there were other Anglo-Italian

barometer and instrument makers in Leather Lane,

including one half of the most famous instrument maker that still

exists today, Negretti & Zambra, which I mention,

again, below. Leather Lane ends at High Holborn, which was

another street known for its barometer makers, and the site of Negretti

& Zambra's most famous shop. Negretti & Zambra's Holborn

Shop

Today, at 82 Leather Lane, Lewis

Martinelli's old shop address, is The Clock House

Pub. It was probably constructed in 1869 by a Mr. Thomas Middlemore Marshall.

From the photo below, you can see that Lewis Martinelli had a wonderful

location, situated on a corner of

the busy street. Today, 82 Leather Lane

But the address of 82 Leather Lane is interesting because it was also

the

address of other Martinelli barometer makers. The one just before Lewis is M. Martinelli & Co., barometer makers at 82

Leather Lane, Holborn, London c. 1810. Here is one of M.

Martinelli's pieces

from that time, that contains a thermometer and a barometer. The

description is from an sales catalog. "A mahogany wheel barometer with broken arch pediment above a

barometer and thermometer, inscribed

'M. Martinelli & Co., 82 Leather Lane, Holborn, London', the case

decorated with inlaid shell and flowerhead motifs c.1810, 39in.

high. £180-250."

The "inlaid shell" and "flowerhead motif" were just coming into fashion

in 1810, and were often called "Sheraton Shell" decoration. Here's

a better look at it, and at the "stringing" wood design often

found around the

edge of the barometer case.

Beautiful, aren't they?

Before M. Martinelli & Co, there was Martinelli P. L. M. & Co.,

a group of Martinelli barometer makers working together in 1799 out of

82 Leather Lane, London.

The L. in the group might have been Lewis, as

Lewis was in London at the time. He married Abigail Marshall on August 8 in

1799, in London. And they had a son, Lewis (Louis), in 1799,

who became a very successful coachmaker. He was apprenticed at age

16 in 1815 to a coachmaker, and followed that profession - doing very

well, and leaving an estate of over £6,000 when he died in 1884 (worth

over £500,000 today). Another son, Alfred Peter Dominico

Martinelli (1806-1849) took up the family profession of barometer maker.

(My thanks to site visitor EH for this information!)

It was traditional in many Italian families,

at the time, to name

the first born son after the father, and the first born daughter after

the mother. Later children were often named after the

grand-parents.

The P. in the group could well be a P. Martinelli who is known to have

worked earlier in Edinburgh, Scotland, and with Ronchetti and Co. in

Coventry.

Italian instrument makers were known to

move around between towns like Aberdeen, Edinburgh, London, Coventry,

and on the continent in Amsterdam. Sometimes the spelling of their

name changed with each move!

Just a note on the Ronchetti family:

Ronchetti, sometimes Ronketti, was another important name among Italian barometer

makers, a bit bigger than the Martinelli name, a bit more famous, and

working a bit longer at it, into the 1800s. The Ronchetti Bros.

worked in London at 172 The Strand until 1880.

One Ronketti, John Ronketti, worked in New York around 1850, and

another, John George Ronketti, worked in New York around 1852-1853.

A major branch of Ronchettis worked out a Manchester, England and

developed special instruments for industry.

John Merry Ronchetti, sometimes written Ronketti, was the most

famous Ronketti barometer maker. He worked as a barometer maker in

Italy and then in England, making the earlier-style stick barometers and then,

later,

the wheel barometers.

This is one of John Merry Ronchetti's very beautiful, early English barometers, from around

1787, signed 180 Holborn, London, his place of work for many years.

He was from the very first generation of Italian barometer makers in

London, who started signing their work, made in Britain, around 1780.

Note that the decoration is not the later, standard, shell decor.

He also has a compass at the top, and a spirit level at

the bottom, with his signature and address engraved on it.

This beautiful flower motif is from another early Italian barometer,

made in 1795, by Charles Chivatti.

There is also a record of a

B. Martinelli making

barometers. He could have been part of the Company, too.

And D. Martinelli was a barometer maker working on Grays Inn

Road, London. c. 1802, a few streets over from Leather Lane. And

later

Martinelli & Ronchetti worked out of 34 Grays Inn Road from 1805 to

1825.

But there was a D. Martinelli who worked at 19 Leather Lane

from roughly 1810 to 1830. He could

also have been a part of the company, or just another relation, even a

distant relation, working further

up Leather Lane at the same time. (In 1840, Negretti, of the famous

Negretti and Zambra company, was working out of 19 Leather lane. See

the left

column for more on Negretti and Zambra.) D. Martinelli made this piece that houses a thermometer and a

barometer, c1810. The selling price is

£2200. The sales catalog description says: "Mahogany

cased 8" dial mercury wheel barometer and alcohol thermometer by D.

Martinelli, 19 Leather Lane, London. Case decorated with floral

and shell inlay. Triple strung boxwood and ebony edge lines.

Scale engraved with horizontal weather positions."

The "horizontal weather positions" refers to the text on the barometer

face, such as "Rain", "Stormy", "Fair", etc. Later, they were

engraved around the dial face, rather than horizontally. For

collectors, this sort of thing is a sign of when the barometer was made. I don't know how long Lewis remained at the 82

Leather Lane address, but some records of barometer signatures suggest he

left in 1811, and there is a barometer record that he lived and

worked in Brighton, England, at 102 London Road, possibly from 1830

to 1838. The address still exists. It is

102 on what is now called the Old London Road. A bypass road sits

to one side of it now, and is the new London Road.

102 Old London Road

The terrace house sits in the middle of a row, and they are not that far

from the coast, in a lovely area.

Here you can see the road, looking toward Brighton and the sea beyond, with the bubble over

the car in the middle, marking the location of the terrace house, on the

left side of the street. It is a lovely street with shops,

charming old houses, pretty gardens here and there, and an old post

office.

But there is also the record

(a census record) that

Lewis's son, William

Martinelli, was

born in Brighton in 1815, so Lewis could well have been living and

working there in 1815 when William was born.

But why would Lewis have left London? I don't know

his reason, but I can guess why immigrants would think twice about

remaining in London in the early 1800s. Living

conditions in London were famously horrible:

filth because there was no sewer system,

cholera because there were only water pumps

that became contaminated, or buckets lowered down into the filthy

Thames River for water (this was not resolved until the 1860s), overcrowding

from inadequate building, violence from rampant alcohol abuse, crime

fuelled by a sharp divide between rich and poor, and exacerbated by

there being no standing police force for the city (not until 1829).

And from 1800 to 1810, the number of Italians emigrating to the Leather Lane area

multiplied rapidly. But they were no longer just craftsmen.

The

Italian poor came in search of work, possessing few skills other

than agricultural skills. The character of the area

changed rapidly from an artisans' area, to a raucous Little Italy.

In 1841, the Italian patriot Mazzini complained that London's Italians

spoke a mash of Comasco (the Lake Como dialect) and English, but not

a proper

Italian. He set up a free school for them, to learn proper

Italian, and to encourage their patriotism for a united Italy. He

firmly believed that once Italy was united into one country, all of

Italy's diaspora would return to live in a prosperous Italy. And

Irish immigrants settled in the Clerkenwell area, too, aggravating the

already difficult living conditions. They settled there because it was

cheap, and because they preferred to live with fellow Catholics for

safety from anti-Catholic bigots. In the

early years of the 1800s, the only

Catholic religious services in London were conducted by Italian priests,

in English and Italian, on the embassy land of the Kingdom of Sardenia. In the early 1800s, 20%

of London's population was from Ireland.

Lewis Martinelli eventually moved back to London, perhaps when

improvements had been made to the city infrastructure and more city

services began to arrive. This was a time of great

growth in London, the population swelling, but as the 1800s

progressed, it also became a time of huge public works

projects:

sewers, fresh water supplies, mass public transport,

new neighborhood developments. In the 1800s, London grew to become

the capital of the western world.

Lewis Martinelli, in his 60s moved his family back to London and made thermometers

and

barometers, and was an optician and looking-glass maker, from 1834 to 1846

at 62 King Street, Borough, London.

The Borough is today

called Historic Southwark. It is the area of London near the south

end of the London Bridge. There is a famous Borough Market that

still exists today.

Over the years, there were records of a barometer maker, or makers,

working under the names:

Lewis

Martinelli, L. Martinelli, L. Martinelli & Co., L. Martinelli & Son, Lewis Martinelli & Son.

At that time, it was quiet usual that several generations of the same

family lived together. Social nets provided by the government

did not exist, so poverty among the elderly was a real problem,

unless they had children to take care of them.

The sometimes dire situations of Italians in London

prompted better-off Anglo-Italians to form social organizations

to provide assistance to the destitute and needy within the Italian

community. They even established a school and an Italian

hospital in London.

During this time,

1835-1845,

Lewis's son, William, made barometers under his own name. W. Martinelli

worked out of 2 King Street, down the street from his father.

Also working out of 2 King Street from 1835-1855 was N.

Martinelli. Another brother, perhaps, a relative?

The very beautiful barometer below is a

a banjo or wheel type barometer made by Lewis

Martinelli in 1835, and you can see how the art had developed since

1810. The case includes many more instruments: a hygrometer

(humidity), a thermometer, a clock, a barometer, and a spirit level. From a sales catalog: "A William IV rosewood wheel barometer with timepiece by Lewis

Martinelli, London. Circa 1835. 'The case with swan neck pediment

and banded with kingwood within ebony and boxwood stringing, with

hygrometer above bayonet-fixed mercury thermometer with bow-front

glass, with convex brass bezel and glass to 6 in. diameter silvered

Roman dial (the clock), with eight day single chain fusee movement with anchor

escapement, blued steel moon hands, convex brass bezel and glass to

12 in. diameter silvered dial engraved to the centre with a

terrestrial map, signed L. MARTINELLI & CO./62 King

Street/BOROUGH, with spirit level below. 50ľin. (127.5cm.)

high. Estimated value 4,000$."

On November 11, 1838, Lewis Martinelli's son, William, married in London. William would go on to have a large family, and

William's sons would follow him into the business, for a while.

After the barometer business declined, the sons found other professions.

There is more on William below. I want to mention here another Martinelli family who was

making barometers in London at this same time. I don't know if

they were relations of Lewis or not, but their story has a

unique element in it.

Alfred Martinelli worked at various addresses from

1839 to 1851:

36

Charlotte Street, Blackfriar's Road, London (1825-1835); Halesworth, 43 Union Street, Borough, London (1839);

96 Vauxhall Street, Lambeth, London

(1843-44); 18 Vauxhall Street, Lambeth, London (1845-51), and

with the

William Day & Co in 1850 at 70 Union Street, Borough, London.

When Alfred died in 1851, his wife Elizabeth took over the business

and made barometers, signed E. Martinelli,18 Vauxhall Street, Lambeth,

London, from 1851 to 1853. Their son, Alfred, later joined her in

the business, for a while. This barometer was made by an Alfred Martinelli.

The text is from a sales catalog. "A MERCURY WHEEL BAROMETER

in a mahogany case with satinwood edging. A swan neck

pediment with central brass finial. A silvered engraved

thermometer scale and main dial. Circa 1830. Signed on the

main dial "A Martinelli, Halesworth". Height 37 " / 94 cms.

£ 580 (US$ 939) (Euro 638)."

William Martinelli's Barometers Lewis Martinelli's son, William Martinelli,

began making his own barometers around 1835, usually labeled W.

Martinelli. His earliest addresses were: 2 King

Street (same address as N. Martinelli, and concurrent with William

signing barometers with other addresses, suggesting he worked on

various projects as needed) (1835-1845) 21 Wells Street, London (1840)

and

Oxford Street, London (1840).

From 1840 onward, William and his wife's family

grew. Census records record the growing family and their addresses, and

the professions that William and his family members listed on the census

forms. By 1841, William had moved his business to 5 Friars Street, Blackfriars

Road,

London (1841), not far from his previous address in the Southwark area

of London, south of the Thames River. William's designs mostly incorporated the 5

elements of his father's last designs: the hygrometer (humidity),

a thermometer,

a clock,

a barometer, and

a spirit level. Some,

however, only had 4 elements. The clock was left out. The

clocks were purchased from clock makers, generally, and inserted into

the designs, making it an expensive element. Perhaps William's

early designs were simpler and less pricy than the top of the line

barometers, to cater to an emerging market of lower income customers?

I can only guess... Here is a clock-less W. Martinelli design that

shows the simplicity of style that denotes a lower price:

In case you're wondering, the

maker's signature was usually placed on the spirit level at the bottom.

You can just make it out here: W. Martinelli 2 King Str, Bor.

If there was no spirit level, then the signature usually appeared on the

face of the barometer, like this:

In 1845, Lewis Martinelli

passed away, at the age of 79. He lived a long life, saw his grandchildren born, and perhaps even his

great-grandchildren. He saw London grow from chaos to the West's

major city. And during his lifetime, Lewis Martinelli created

works of art that would be prized possessions in countless families over

the years, and that still command hefty prices for anyone wanting to own

an L. Martinelli barometer.

It is also around this time that

William started to sign his work:

W. Martinelli & Son, 2 King Street, London.

Here is one of those barometers. You can see

that the woodworking is more sophisticated than the earlier model, but

he still has a mirror in place of the clock. The text is from a

sales catalog. "A 19th Century mercury wheel barometer and

thermometer with broken pediment, dry/damp indicator, thermometer,

mirror, silvered dial and spirit level by W Martinelli & Son, 2 King

Street £200-300"

Here is another W. Martinell & Son barometer that includes a

clock: "Mahogany five glass banjo clock barometer,

signed W. Martinelli & Son, 54, Snows Fields, Boro, the 10"

principal silvered dial within a satinwood banded shaped case

surmounted by a broken arch swan neck pediment. Estimate:

800-1200"

Soon after that, perhaps even as soon as 1851 when the census was

carried out, William signed his work:

W. Martinelli & Sons, 54 Snows Fields,

Borough, London, again in the Southwark area, and not far from the

previous addresses.

William and his family appeared in the census of 1851 and

were listed as living at 54 Snows

Fields, Bermondsey, London. Snows Fields (today Snowsfields), Bermondsey.

Here is a

photographic image from 1881 of houses in Bermondsey Street, just

off Snowsfield. These were some of the old houses

from Elizabeth I's era that were demolished in Bermondsey to build new,

better housing for London's growing population. This is 48 Snowsfields today, the first address on the

left. It is the sort of building William would have lived in,

above, and had a workshop, below. This stretch of William's era's

housing is the only stretch that still exists in this recently renovated

area. I don't think this part will last long.

Something the 1851

census shows clearly, is that large families were the norm at this time.

Reliable birth control did not exist, even if families wanted to use it.

And the toll on women of

near continual pregnancies was very high in terms of poor health and

early

death.

When retracting family trees through this period,

many find that quite a few men married more than once, upon the

death of their wife. Families were, contrary to popular opinion,

quite often composed of a father, step-mother, and the children from

more than one mother.

And the streets of London were teeming with children, just as

the streets of many developing countries today are teeming with

children, for similar reasons. But childhood deaths were common

too, during this time of smallpox, influenzas, measles, infections and

poor sanitary conditions.

The death of a child was a terrible curse on all families at this

time, rich and poor.

Here is another very beautiful

William Martinelli barometer. The text is from a sales

catalog. "Mid-19th Century, in a boxwood and ebony strung

mahogany case with flame veneer, and with five dials for the various

instruments and a spirit thermometer and butler's mirror. 38"

high, 10" wide, 2" deep." The estimated price is 1500.US$"

Later, William Martinelli signed his work: W. Martinelli, Snows Fields, Bermondsey,

or W. Martinelli, or 120 Snows Fields, Bermondsey, London.

This was likely because he moved, and was working alone again.

By the time the 1861 census came around, William was 45 and still

listed as a barometer maker and living with his wife and their children.

The children had found professions of their own, such as Tinman (a metalworker who made, sold and repaired tin pots and

pans), and a Laborer. London was booming by now.

Public works were everywhere to be seen. Making the city livable

for the millions already there, and for the projected millions due to

arrive in the coming decades, was a major priority of the borough and city

governments.

The public works created jobs, not just temporary jobs.

Young men could find work driving trains and trams, installing and

maintaining gas lighting, building and maintaining paved streets and

sidewalks, and policing the city. And then there were the jobs in

the service industries that helped provide food and for the other needs of

London's millions. Barometer making was no longer a viable profession.

So when the 1871 census came along, when William and his wife

were 55, William described himself as an optician (the census forms were

filled in by the head of the household).

William's

death was recorded in March of 1891, aged 75.

William lived and worked in London all his long life. His mother

and his wife were not likely Italian immigrants. Perhaps, what

little of Italy's culture that remained with William by the end of his

life, were his barometer making skills, and his last name.

To get an idea of what London was like about this time (1905),

go below to view a film from the

era. It is fascinating! Many Anglo-Italians left Britain during the

period from 1900

to the post-WWII years. World Wars,

internments and the loss of empire for Britain, pushed many to make the

leap and move to Australia, Canada or New Zealand, for example, for a fresh start.

Some had no choice. Britain transported many Anglo-Italians, those

without citizenship, abroad. Part of the fresh start for some immigrants was a

name change. For some that was to avoid anti-Italian

bigotry in their new home country. Some had changed their names

earlier than that, for the same reason. For others, it was just part of the fresh

start they wanted.

Little did they know that their descendents would ask

'Where did I come from?' and try to retrace how they came to be where

they were. And if they found they were of Italian descent, they

would try to identify the first in their family to leave Italy, and

to know why they left, and if there were still relatives in Italy.

Many descendents of those early Italian immigrants

try to rediscover their Italian heritage by traveling to Italy,

studying Italian and Italian history and culture, and by cooking Italian

food. As you can guess, I applaud their efforts! I am an

Italophile. Below are more goodies about

barometer makers, modern London and old London...

Throughout this period, there were Anglo-Italian barometer makers working in Glasgow, Edinburg,

Manchester, Bristol, Bath and other towns. The woodworking

skills were similar to the skills needed to make musical

instruments. The skills needed to make the finely crafted instruments set into

the wood casings, were useful in making optical and surgical

instruments. Barometer makers often made other scientific

instruments, and were opticians, too. At the antique clock and barometer dealers

P. A. Oxley,

you can see images of many Anglo-Italian made barometers from the

1800s, and their values (also see Barometer World's

Mercury

Wheel Barometer Page). They have this informative summary: "Wheel barometers (sometimes

called banjo barometers) were used throughout the 18th century

but they did not become popular until C.1780. They were then

made mostly in London by Italian Craftsmen. The wheel barometers

at this period featured crossbanded sides, high quality veneers

and engraving and very finely made cast brass bezels.

As the 19th century approached

the volume of wheel barometers increased and an almost standard

form was being produced which is sometimes called a Shell

Barometer. This was made until C.1830 when other features such

as Mirrors and Hygrometers became more popular and the 5 Dial

Barometer was introduced. Towards the end of the 19th century

when the Aneroid Barometer was found to be easier to transport

and cheaper to make, the Mercurial Wheel barometers eventually

came to an end."

Two villages on facing shores of y-shaped Lake Como

Edwin Banfield is a

historian who has specialized in the history of barometer making in

England. His books, like Barometer Makers and

Retailers from 1660 to 1900 (pub. 2000), and The Italian Influence on English Barometers from

1780 chart the history of skilled Italian immigrants.

He says the barometer makers came

mainly from the Northern region of Lake Como, Lombardy, Italy.

Italy was very poor at the time, and rife with political struggles

that would eventually lead to the unification of the peninsula and

the birth of the Italian nation.

Italy also had a rich history in

scientific achievement and a large pool of skilled artisans.

Italian barometers were of a more practical and beautiful design for

sale to wealthy individuals. And they were housed in a

beautiful wooden cases reminiscent of musical instruments, together

with other goodies such as a spirit level, a thermometer, and later

with a clock, a

mirror, and a hygrometer.

Those artisans chose to leave Italy, sometimes for only a part of

the year, others for good, but often sending money home to the

relatives left behind. Some sent for the relatives to join

them in businesses they established abroad.

The area around Lake Como is very

difficult terrain to cultivate, and most Italians at the time relied

on what they could produce on their small plots of land, so life was

precarious there, and not suited to supporting the large families

that were the norm.

The barometer makers went to wealthy France, The

Netherlands and Britain, mainly. And they immediately made an

impact on the local production of barometers. The local

artisans were forced to copy the Italian designs, designs the

customers craved. Foreign makers hired Italian artisans, some

formed partnerships with Italian artisans.

The older model of barometer was the Stick Barometer, which housed the

long mercury tube in the casing, and had the prediction panel at the

top.

The Wheel Barometer, translated the tube's reading, using a pulley

system attached to the mercury tube hidden in the back of the Banjo

Barometer's case, to translate the mercury movements to a round dial

with a clock hand that pointed to the weather prediction.

Here is a photo of the back of the a Banjo Barometer case, open to show

the tube and pulley system.

A Banjo Barometer case included many small pieces, as can be seen here

in the image from an

English barometer restoration shop.

The town of Cantu, just south of Lake Como, has been know for as long as

anyone can remember for furniture making. It is still the biggest

industry in the town today.

This nightstand was made there, about 1930, for a Lake Como villa.

You can clearly see the frame, mirror, carving, and cabinet skills that

were used by the early Italian immigrants to London to make mirrors,

frames and barometer cases.

This is Mr. Banfield's list of barometer makers

working in London from roughly 1800 to 1900. You can see that

it was dominated by Anglo-Italians.

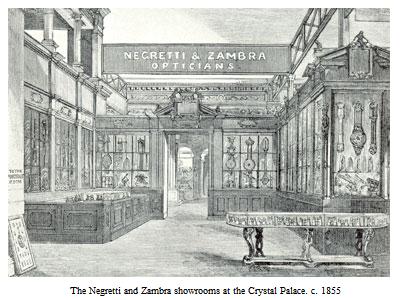

NEGRETTI, Henry One of the most famous of the Anglo-Italian Optician/Barometer

makers was Negretti & Zambra. This is a drawing of their

London store in Holborn, on the Holborn Viaduct (High Holborn),

which crosses Leather Lane. (Visit the charming Negretti & Zamba

history site.)

Henry Negretti was from the Lake Como area, too, and in 1843,

he set up shop on Leather Lane. In 1850, Mr. Negretti and Mr. Zambra set

up shop together, and moved offices several times as their business

grew. Over the years, their firm made: thermometers, underwater thermometers, barometers, battleship barometers, optical lenses terrestrial telescopes, astronomical telescopes, theodolites, spirit levels, gun sights 1920s to today - aircraft gauges.

'The mountainous country of northern Italy provided a sparse living

for the people, and during the winter months the farmers and shepherds

would turn their hands to crafts of all kinds. These skills were

handed down from father to son, and the things they made would be

carried north over the Alps by many hundreds of the younger generation,

to be sold in the more prosperous areas of Europe. These

travelling salesmen would spend a few years abroad and then return home,

to settle down with their families and in turn pass on the trading to

their sons. 'They were quick-witted, intelligent people, and they learned fast.

Once Torricelli's experiment had evolved into the barometer they began

adding it to the religious images, laces, silks, thermometers, musical

instruments and telescopes that were already their stock in trade. 'The Italians did not come to England to sell barometers until the

later 1700s and early 1800s. There had always been Italian

acrobats, artists and musicians in England, but they had been few.

There were several reasons for the tide that began to flow in the last

years of the 1700s.

'Although it had escaped invasion, England had been fighting Napoleon

for nearly twenty years, and by the time he was finally defeated at

Waterloo, England's wealth had been drained away, and she was bankrupt.

Unlike the Continental countries that had been invaded, however, England

had retained her stability and her national institutions. 'Furthermore, the countries of the New World were clamoring for the

products of her industrial revolution, so that her recovery was

comparatively swift. As prosperity grew, the rise of the wealthy

middle classes brought an enormous demand for consumer goods of all

kinds, and the enterprising Italians took advantage of that rising

demand. 'Soon after 1790, their markets in France closed to them by the

revolution, the Italians began to come to England. Looking-glass

makers, picture framers, bird cage makers, ice cream makers and sellers,

and thermometer, telescope and barometer makers arrived in a growing

tide. There were also, of course, large numbers of relatively

unskilled people who followed their traditional occupation of hawking

their countrymen's wares around the countryside. 'The early arrivals made for London and settled in the Clerkenwell

area, perhaps because its narrow streets and little enclosed courts

reminded them of home. Those who prospered would send home for

relatives to join them, and soon the place became so full of Italians

that it was known as "Little Italy". 'They kept very much to their old ways, holding religious processions

on the saints' days, and turning out for church in their traditional

dress. In 1863 a new, Italian style church was opened in

Clerkenwell by Cardinal Wiseman. In a later newspaper article,

Geoffrey Fletcher described it as " a slice of unadulterated Italy

dropped into workaday Clerkenwell". The church escaped the bombing

of the Second World War, which devastated much of the area.

'The early settlers pursued their callings with varied success.

The mosaic floors of Victorian pubs and public lavatories were mostly

laid by Italian immigrants. The hawkers quartered the countryside,

selling their multifarious wares. Ice-cream sellers pushed their

brightly painted barrows through the streets, crying "ecco, un poco" or

"here, a little". 'The Gatti family established the famous West End restaurant and made

ice-cream respectable and fashionable. Barometer makers like

Negretti and Zambra, Ronchetti, Casella, Tagliabue and Corti, to name

but a few, set up and devloped their businesses.

'This practice became virtually universal, and it is very difficult

to know whether the name on a barometer is that of the maker, or even if

any single maker was involved. Even well-known makers bought fin

from each other. For example, Negretti and Zambra regularly

supplied sixteen other makers in London alone, and an even longer list

throughout the country. Research shows that barometers with the names of country makers on

them were usually bought in from the Italians in London, and then sold

with the retailer's name on the case. An example of this comes

form the Devonshire firm of jewelers and clockmakers, W. J. Cornish of

Okehampton."

(This is a transcription of an article from the wonderful site Barometer

World. I've put it here because I can no longer find it on their

site. Be sure to visit their site for their wonderful info on

barometers: Barometer World's

Mercury

Wheel Barometer Page.) Clerkenwell Here is a bit from

Hidden

London about Clerkenwell's Little Italy:

As well as the Italian church

of St Peterís, there a few local shops and services run by members

of the Italian community, but the number of these premises is

declining. The greatest concentration of Italians in the area

was around the end of the nineteenth century. Before this, the Saffron Hill

vicinity had been notorious for the pickpockets and fences portrayed

in Oliver Twist and the authorities were glad to see these

supplanted by the more respectable Italians. Londonís Italian population is

now spread more thinly throughout the capital, but Sunday worship at

St Peterís still provides a focal point. The Processione della

Madonna del Carmine, held on the Sunday after July 16th, is Little

Italyís most important event. Except during wartime it has taken

place every year since 1896.

Wikipedia's page

for Clerkenwell A wonderful article, as a PDF, about the

founding of the Italian church, with plenty of fascinating

information about London at that time, and about the Italian community

in London.

Click

here for an account of Italians in London from 1800 to 1960 by

reporter Varusca Calabria for Culture 24, in 2006. And for a lovely site with stories and images:

De Marco's. In the late 1800s, the artist Frank Lewis Emanuel

(1865-1949) tried to document parts of London that were slated for

demolition, or were in threat of fast disappearing. London's middle-age and Renaissance buildings are

nearly all gone. Artists over the years tried to document the

disappearing city, much as the artist Borbottoni documented Florence, Italy's medieval district before

it was demolished. If you wish to know more about what life was like

in the 1800s in Britain, visit the Channel 4

History of London site. And check out the

120 photographs of London from 1875 to 1887, made by the Society

for Photographing the Relic of Old London. He collected his sketches together in a book

called

Disappearing London. His illustrations were used for

the 1913 book

A Londoner's London by Wilfred Whitten. Here are a few

of them showing old Holborn and Old Leather Lane, mixed together

with photos and other cool images. Leather Lane. I think we are looking at the

entrance to Leather Lane, in the right in the drawing, from High Holborn.

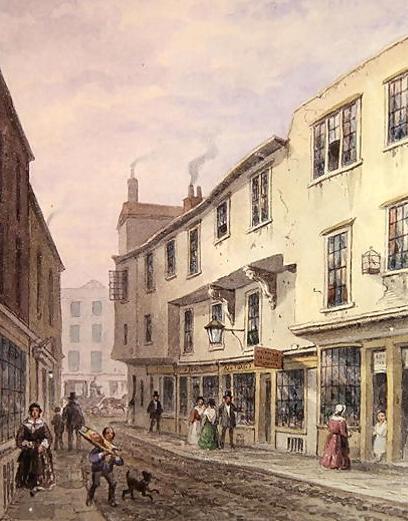

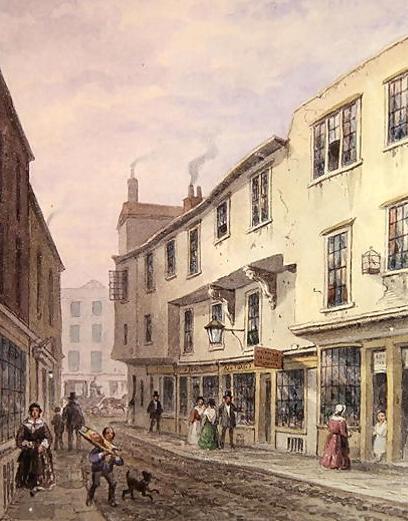

This is another view of old Leather Lane

looking the other way, from Leather Lane to High Holborn,

from a

1857 painting by

Thomas Hosmer Shepherd entitled:

Old House at the Entrance to Leather Lane.

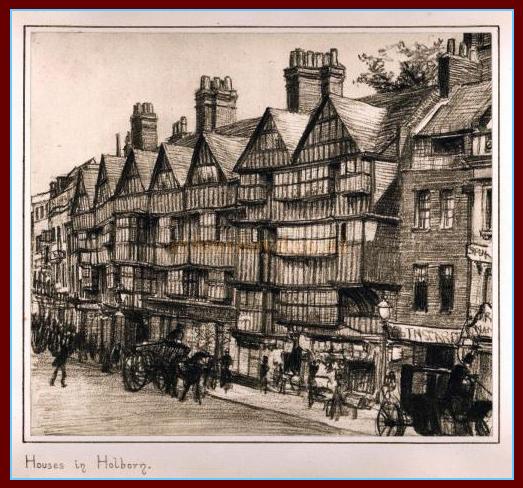

This is a row of Houses in Holborn.

Here is an image from today of this line of houses

built in 1586, known as The Staple Inn, and famous as one of

Central London's few remaining Tudor buildings.

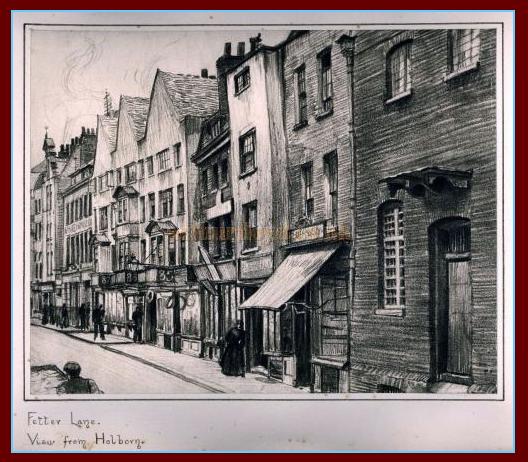

Fetter Lane, as seen from High Holborn.

Fetter Lane runs off one side of High Holborn,

while Leather Lane runs off the opposite side of High Holborn.

They looked very similar in architecture and shop-fronts. The

maximum 5-story buildings, often constructed partially with wood,

were all torn down and replaced by larger stone and concrete

structures that could house more people. Here are photographs showing Barnard Inn, the

three-pointed row of houses in the drawing above. The Barnard

Inn was an old Courtyard Inn. Stages, people, carriages, etc.

could drive into the courtyard and enter the Inn from there.

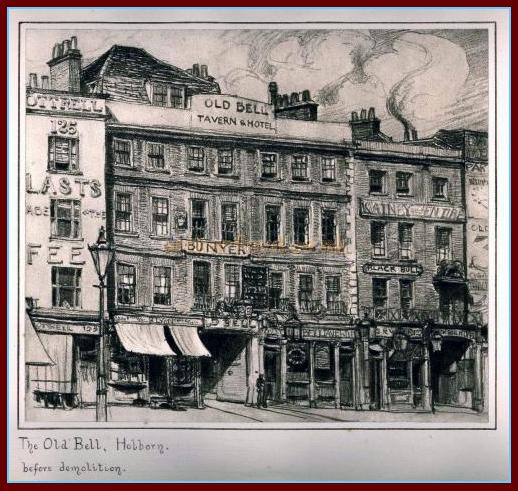

The Old Bell Tavern & Hotel on High Holborn, not long before it was

demolished.

Here's a photograph of the same building at the same time.

Click

through to read more about the building. It, too, was a

Carriage Inn. In this photo you can clearly see the entrance

into the courtyard for the carriages. The Post carriages

stopped at the Old Bell, carrying mail and passengers. This is an image of old houses on

Bermondsey Street in Southwark, houses that were said to date

from the time of Elizabeth I.

This fascinating film (4 mins) is from London

1905. It shows the streets congested with horse-drawn trams and

carriages, pedestrians everywhere in the street, and if you look

closely, you'll spot some motorcars, too. It gives a good idea of

the chaos of London then (not so different from now!).

This film is only 38 seconds long but it is beautiful. It shows

the world passing by on Blackfriar's Bridge in 1896.

Here are some interesting

books on the subjects mentioned on this page, available via Amazon.com

(some are VERY pricey, sorry, but they look wonderful. CM).

If you'd like to see what Como, Lombardy in Italy is like, you can

visit the

Como Town Hall site, in Italian, where they offer a

virtual tour,

but I recommend Google Maps' Street View: The Italo-Swiss emigrated to London, too. This

page from a 75 year old Swiss radio station offers a wonderful

description, in Italian, of the immigration of the Ticinesi from roughly

1800 to 1905, when the Alien's Act stopped mass immigration into

Britain. They even give details up to 1987, when the last Ticinese

restaurant in London closed it's doors. This is a great history site with lots of images of

20th Century

London. If your Italian family passed through Britain, and

you want to know more about them, there is a wonder site that can help:

the Anglo-Italian Family

History Society. Among their treasures is this

Table

of Italian Immigration Patterns in Britain.

London's

Hyphenated Italians and Martinelli Barometers

![]()

Italian

Immigrants in London

1700s to 1911

London Martinellis

Barometers, Thermometers, Frames, Mirrors and

Wood-Working

Martinelli Barometers on Leather Lane

Leaving London Behind

Back to London, New Location

Alfred and Elizabeth

Martinelli

Anglo-Italian Barometer Makers

AGNEW, Thomas & Sons

AIANO, Charles

ALBERTI, Angelo

AMADIO, Francis

AMADIO, J

ANONE, Francis

BELERNO, D.

BARNASCHINA, A.

BARNASCONI, M.

BELLATTI, Charles

BELLATTI, Louis

BETTALLY, C.

BIANCHI, George

BOLONGARO, Dominic

BRAGONZI, P.

BREGAZZI, C.

BREGAZZI, Innocent & Peter

BREGAZZI, Samuel

BROGGI, Gillando

CALDERARA, A.E.

CALDERARA, S & A

CANTI, C.A.

CASARTELLI, A & J.

CASARTELLI, Joseph

CASARTELLI, Lewis

CASELLA, C.F. Ltd.

CASELLA, L.

CATTELY & CO.

CETTA, John

CETTI, Edward

CETTI, Joseph

COMITTI, Geronimo

COMITTI, Joseph

COMITTI, Onorato

CORTI, Jno

CORTIES & SON

CROSTA

DANGELO & CADENAZZI

FAGIOLI, Dominic

FAGIOLI, J.

GALLETTI, Antoni

GALLETTI, John

GALLY, Charles

GALLY, Peter & Paul

GATTY, Andrew

GATTY, Charles

GATTY, Domco

GATTY, James

GATTY, Joseph

GERLETTI, Charles

GERLETTI, Dominick

GIANNA, Lewis

GIOBBIO, J.B.

GIUSANI, P.

INTROSSI, P.

KALABERGO, John

LAFFRANCHO, J.

LIONE, Dominick

LIONE, James

LIONE & SOMALVICO

LOVI, Angelo

LOVI, Isabel

MAFFIA, Dominic

MAFFIA, Peter

MALACRIDA, Charles

MANGIACAVALLI, J.

MANTICHA, Dominick

MANTICHA, Peter

MANTOVA, P.

MARIOT, James

MARTINELLI, Alfred

MARTINELLI, D.

MARTINELLI, Lewis

MARTINELLI, P.L.D.& CO.

MARTINELLI, William

MAZZUCHI & Co.

MOLINARI, Charles

MOLTON, Francis

NEGRETTI & ZAMBRA

NOSEDA, John

PASTORELLI, Alfred

PASTORELLI, Anthony

PASTORELLI, Fortunato

PASTORELLI, Francis

PASTORELLI, John

PASTORELLI, Joseph

PASTORELLI & RAPKIN

PEDRONE, L.

PEDUZZI, Anthony

PEDUZZI, Joseph & Co.

PELLEGRINO, Francis

PEOTE, James

PEOVERY

PEURELLY, C.B.

PINI, Joseph

PITSALLA, Charles

PIZZALA, F.A.

POLTI, T.L.

POZZI, Peter

PRIMAVESI BROS.

RABALIO

RISSO, John

RIVOLTA, Alexander

RIVOLTA, Anthony

RIZZA, A.

RONCHETI & GATTY

RONCHETTI, C.J.

RONCHETTI, J.B. & J.

RONKETTI, J.M.

ROSSI, George

SALA, Dominico

SALLA, J. Bapt.

SCHALFINO, John

SILBERRAD, Charles

SILVANI & CO.

SOMALVICO, Charles

SOMALVICO, James

SOMALVICO, Joseph

SORDELLI, J.

SPELZINI

TAGLIABUE, Angelo

TAGLIABUE, Anthony

TAGLIABUE & CASELLA

TAGLIABUE, Cesare

TABLIABUE, Charles

TABLIABUE, John

TABLIABUE & TORRE

TARONE, Anthony

TARONE, Peter A.

TARRA, N.

TESTI, G & CO.

TESTI, J.

TORRE, Anthony

TORRE, G.B.

VARGO, F.

VECHIO, James

ZAMBRA, J.C.

ZAMBRA, J.W.

ZAMBRA, Mark W.

ZANETTI & AGNEW

ZANETTI, Vincent

ZANETTI, Vittore

Negretti & Zambra

Barometer World - Italians and the

Barometer Makers

"It

was at this stage that the Italians appeared on the scene in England.

It had been soon after 1670 that Italian hawkers (travelling sellers),

began to sell barometers all over the European mainland. Most of

them came from northern Italy, from the district around Lake Como, and

they were following in the footsteps of many past generations of their

countrymen.

"It

was at this stage that the Italians appeared on the scene in England.

It had been soon after 1670 that Italian hawkers (travelling sellers),

began to sell barometers all over the European mainland. Most of

them came from northern Italy, from the district around Lake Como, and

they were following in the footsteps of many past generations of their

countrymen. 'Prior

to the French revolution, the markets they could reach over land, or

down the great rivers, would give them plenty of trade. After the

revolution, and the subsequent ravaging of the Continent by Napoleon,

things were very different. They would naturally look towards the

one major country that had not been over-run by the French:

England.

'Prior

to the French revolution, the markets they could reach over land, or

down the great rivers, would give them plenty of trade. After the

revolution, and the subsequent ravaging of the Continent by Napoleon,

things were very different. They would naturally look towards the

one major country that had not been over-run by the French:

England. 'Although

"Little Italy" became the centre for Italians in England, there were not

by any means confined to the capital. By the middle of the 1800s

there was hardly a town in England or Scotland of any size that

did not have at least one Italian barometer maker, plus of course others

in different trades.

'Although

"Little Italy" became the centre for Italians in England, there were not

by any means confined to the capital. By the middle of the 1800s

there was hardly a town in England or Scotland of any size that

did not have at least one Italian barometer maker, plus of course others

in different trades. 'The

barometer makers formed a close community and kept in touch with their

less fortunate countrymen. The smaller firms would buy tubes and

other parts from those with more extensive workshops, and assemble them

into cases marked with their own names. The cases were often made

at home by Italian wood-carvers, or in the case of English makers, by

local cabinet makers. They would be paid a few shillings each for

the cases, which would be finished off in the workshops of the bigger

firms.

'The

barometer makers formed a close community and kept in touch with their

less fortunate countrymen. The smaller firms would buy tubes and

other parts from those with more extensive workshops, and assemble them

into cases marked with their own names. The cases were often made

at home by Italian wood-carvers, or in the case of English makers, by

local cabinet makers. They would be paid a few shillings each for

the cases, which would be finished off in the workshops of the bigger

firms. "A

nickname applied to the western side of Clerkenwell because of its

strong Italian connections, which go back at least two centuries.

Also once known as Italian Hill, its boundaries are recognised as

Clerkenwell Road, Farringdon Road and Rosebery Avenue.

"A

nickname applied to the western side of Clerkenwell because of its

strong Italian connections, which go back at least two centuries.

Also once known as Italian Hill, its boundaries are recognised as

Clerkenwell Road, Farringdon Road and Rosebery Avenue.

Giuseppe Mazzini, the writer, patriot and revolutionary, lived in

Laystall Street and founded an Italian language school in nearby

Hatton Garden in 1841."Holborn