Candida Martinelli's Italophile Site

Main

Page This family-friendly site celebrates Italian culture for the enjoyment of children and

adults. Site-Overview

Quick links to quince recipes on this page:

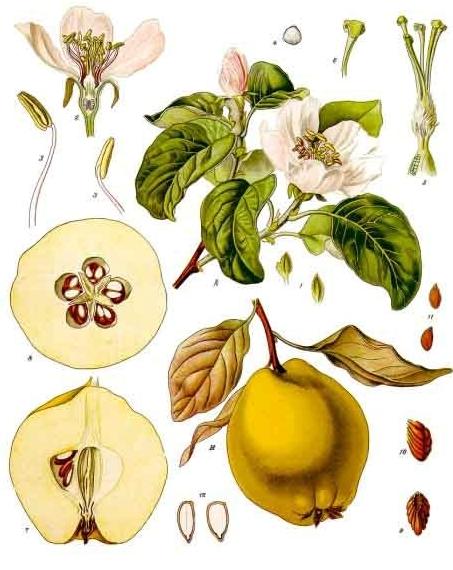

Quince fruit are very fragrant, yellow, apple-like fruit that have been cultivated

since ancient times. All but one variety of quince need to

be cooked before they can be eaten. But once they are cooked,

they are delicious! If you've never eaten cooked quince, you've

never enjoyed nature's wonderful mixture of pear, apple and lemon.

The shape is usually like an apple (sometimes like a pear - pere

cotogne); the texture is a bit grainy like

a pear; the flavor is citrusy like a lemon.

Ancient Romans loved quince, and planted the trees all over their

empire. The quince planted in the warm climates around the

Mediterranean Sea remain mainstays

of those area's fruit production, and quinces are part of local diet. But those trees planted in the colder, northern

climates, mostly died off and were eventually not replanted.

In those countries, today, the quince fruit is considered 'forgotten

fruit'. Quince trees are cultivated, counted and protected by hobbyist and professional

associations. Cooking with quince is considered quaint, or

even chic. Romans ate quince in savory and sweet dishes.

A quince fruit in Italian is una cotogna or una mela

cotogna, plural mele cotogne. The quince tree is un cotogno or a melo cotogno.

And quince jam is una cotognata or marmellata di mele

cotogne. Tuscany and Sicily are the regions of Italy most closely

associate with quince recipes today. In Latin, the quince is cotoneum, the genus name is Cydonia Oblonga, or

cotoneum malum or cydonium malum.

Malum is the Latin word for apple.

The Latin quince name comes from the Greek: kydonion melon or

'Kydonian

apple'.

We have a quince tree in our garden and it is my favorite of all

our fruit trees for many reasons. Every spring it is covered with tiny pink-white flowers that

smell divine. I fertilize the flowers with an ear swab,

starting at one point around the tree, touching the swab to the

center of as many flowers as I can reach. Then it move around

the tree and continue fertilizing the flowers with the swab. By mid-summer I can see the product of my 'quince-sex': the

tree is full of small, green, fuzzy fruit. A quince tree can carry more fruit than the average apple tree.

The quince tree is often used as a base for many pear varieties,

which are grafted on, so they can bear more fruit and are more

resistant to bugs. By fall, the small green fruit has grown, turned yellow, and lost much of

it's fuzz. The day after I pluck them from the tree, the citrus perfume

intensifies 1000-fold. I fill the house with them and we enjoy

the scent for as long as we can.

Then I cook them.

There are some funny things about

the humble quince...

People have been cooking with quinces throughout the Mediterranean

region for centuries. Quinces play a part in many cultures' rituals. The cultivation of the quince predates the cultivation of apples in

the Mediterranean Sea and Near East, where it is a native plant.

So in Western mythology and in the Bible, when there is a reference

to an 'apple' or a 'golden apple' the reference is really to a quince.

Some Recipes Quince puree is the basis of most quince sweets

recipes. There are two ways of making it: the

traditional way, and the modern way. Traditional Way: Clean the quinces of the fuzz. Quarter the quinces. Boil the pieces for about 1/2 hour with a

quartered lemon, until a fork enters the flesh easily. The

lemon stops the quinces from oxidizing, keeping the color nice a

fresh. Let the quinces cool. Then cut out the

cores and seeds, and peel off the skin (many recipes have you

leave the skin on for a greater acidity). Mash up the quince pulp with a fork or with a

hand-grinder, or run it through a food processer, to make your

puree. Modern Way: Clean the quinces of the fuzz. Dice the quinces, removing the cores and seeds. Microwave the diced quinces in a glass container

covered with a glass top. Cook it in 5 minute bursts, and

between the bursts, mix the fruit around so it cooks evenly.

It should be soft after about 15 minutes of cooking. Mash up the quince pulp with a fork or with a

hand-grinder, or run it through a food processer, to make your

puree. This puree comes out slightly dryer than when you

use the traditional method, which is better for making a thick

quince paste.

Prepare the quince puree as above. Put in a stainless steel pot equal parts puree

and sugar. (You can use less sugar, down to 1/2 the quince

puree weight, and still get a nice jam.) Put the quince pot on a burner and stir it continually as it cooks, using a wooden spoon. Let it boil for

at least 1/2 hour. You can add cinnamon, nutmeg, ginger and/or

clove, to taste, for a spicier, 'warmer' jam/chutney. You can jar the jam, or pour it into a mold. Let

the molded jam cool, then turn it out. It will stay good

for quite a while like this, but it is best to refrigerate it. Usually people use the jam or cut off pieces of

the mold and spread it on

bread, for breakfast. I find it very filling, holding off

hunger for a long time, and it is very nutritious. This next recipe is from a

medieval cookbook from Andalusia Spain that I have on my site.

The recipes from Muslim Spain are precursors for many recipes that

are often deemed traditional Italian, or European, recipes. Quince jam and jelly are two of such recipes.

The 9th century Muslim rulers of Sicily introduced citrus cultivation and the

cultivation of quince to the island, and the recipes for cooking with

it, including these recipes. Take a

ratl [1 ratl=468g/1lb]

of quince, cleaned of its seeds and cut into small pieces.

Pound it well until it is like brains [or grate it]. Cook it

with three ratls [1

ratl=468g/1lb] of

honey, cleaned of its foam [heated and skimmed], until it takes the

form of a paste. It is also made by another, more amazing recipe:

take it as said before, and cook it in water alone until its essence

comes out. Clean the water of its sediments [filter the liquid

from the pulp], and add it to an equal amount of sugar. Make

it thin and transparent, without redness [cook it until it lightens

and thickens], and what you have made will remain in this state [a

jelly]. Its benefits: it lightens the belly that suffers from bile,

it suppresses bitterness in the mouth, and excites the appetite.

And I say it keeps bad vapors from rising from the stomach to the

brain [indigestion].

Prepare the quince puree as above. Put in a stainless steel cooking pot with equal parts puree

and sugar. Put the pot on a burner and stir

continually

as it cooks, using a wooden spoon. Let it boil for

at least 1 hour. As it

cooks, more moisture will escape, and the mixture will darken to

a red wine color. Pour it into a mold or a baking dish, keeping

the thickness no more than 1 inch or 2 centimeters. In North Africa, they sometimes pour half of the

paste into a pan, then cover it with sliced almonds, then pour

the rest of the paste over the

almonds. Let it cool, then

turn it out. It will stay good for quite a while like

this, longer than jam. This paste is often sliced and served with cheese.

And this firm paste is the best basis

for the following candy recipes.

Prepare the quince paste above. Slice it into the candy shapes you want, usually

cubes or strips. For sugar-covered candies: roll the

quince pieces in

sugar and let them dry on waxed paper overnight. You can

turn them over and let them dry one more day, if you think they

are still too damp. Then

store them in an air-tight container. They remain good for

a very long time. For chocolate covered candies:

break a chocolate

bar into bits into a bowl. Microwave it for 30 second

intervals, stirring it between the intervals, until it is

melted. (A small amount of chocolate is usually ready in

30 seconds.) Then drop a few quince pieces into

the melted chocolate. Remove them with a fork, and set

them on waxed paper. They set well 1/2 an hour in

a fridge, or a few hours at room temperature. Store

them in an airtight container.

For the fruit bottom: 550 grams of cored and diced quince 200 milliliters of sweet Spumanti wine 5-6 teaspoons of sugar Cook the fruit in the Spumanti and sugar, stirring,

until it gets soft (about 15 minutes). For the meringue: 3 egg whites 100 grams of powdered sugar A pinch of salt A pinch of cinnamon (Translated from Italian from the blog

Pan con l'olio. I suggest can you try, too, to mix the

cooled fruit gently into the whipped whites and cook them like that

in greased cups. Then sprinkle them with cinnamon just before

you serve, ideally with a scoop of vanilla gelato on the side.)

Really, you can adapt any apple recipe to become an

Apple and Quince recipe. They complement each other perfectly. For example, make your tart crust and spread it

out in your tart form. Spread quince puree over the crust,

then arrange sliced apples that have been tossed in lemon juice

over the jam. Cook your tart as usual. Or arrange the apples directly on the tart

crust, then spoon quince jam over the apples. Cook your

tart as usual. I add quince puree to the apples in my

apple pies. It adds a lemony taste and a pear-like

texture, and a heavenly scent to the pies. No apples in this one, but any pumpkin pie

recipe you have can be used for quince. You replace the

pumpkin puree with quince puree, making it a quince custard pie,

or a quince chiffon pie, or a quince cheesecake... Yummy!

Here are some more recipes from the

Andalusian Cookbook. The savory dishes are still cooked in this

way throughout North Africa and the Middle East. They give you

an idea of how you can use quince in your own cooking with various

types of meat. The acidity of the quince adds to the dishes, as

does the red color when it is cooked a long time, and

quince thicken the sauces of stews. The sweet dishes stress the medicinal value

of the quince for the stomach and intestines. It can have a

slight laxative effect if eaten warm or together with something

warm. Take [dead] sexually mature chickens and clean and

put in a pot. Put with them the juice of sour pomegranates [a common

ingredient in North African cooking], quinces and apples, and oil

and onions and cilantro. [Cook.] When it is about done, throw in a little mint and some Chinese

cinnamon [cassia] and dry coriander, and cover with ten peeled

almonds and serve. Kill young chickens and clean and put in a pot [with

water]. Put with them crushed garbanzos and cut-up onion. Put on the

fire, and boil until done. Squeeze pomegranate juice and quince juice and pour into the pot,

and cover with bread crumbs, and sprinkle tabîkh raihani ["basil

near-wine", a mild wine not proscribed by Islam] on it and ladle out

and serve. This is a good food for the feverish, it excites the

appetite, strengthens the stomach and prevents stomach vapors from

rising to the head. Take the flesh of a young fat lamb or calf, cut in

small pieces and put in the pot with salt, pepper, coriander seed,

saffron, oil and a little water. Put on a low fire until the meat is

done. Then take as much as you need of cleaned, peeled

quince, cut in fourths. And sharp vinegar, juice of unripe grapes

[verjuice] or of pressed quince, and cook for a while and then use

[over or mixed with the meat]. If you wish, cover with eggs and it comes out like muthallath. Take meat and cut it in pieces which then throw in a

pot. Throw on it two spoons of vinegar and oil, a dirham [1 dirham=3.9g/3/4tsp] and a

half of pepper, caraway, coriander seed and pounded onion. Cover it

with water and put it on the fire. Clean three or four or five quinces and chop them up

with a knife, as small as you can. Cook them in water. When they are

cooked, take them out of the water. When the meat is done throw in

it this boiled quince and bring it to the boil two or three times.

Then cover the contents of the pot with two or three eggs and

take it off the fire, leave it for a little while. When you put it

on the platter, sprinkle it with some pepper, throw on a little

saffron and serve it. Leave overnight whichever of the two [birds] you

have, its throat slit, in its feathers. Then clean it and put it into a pot and throw in two

spoonfuls of rosewater and half a spoonful of good murri [use soy sauce], two

spoonfuls of oil, salt, a fennel stalk, a whole onion, and a quarter

dirham [1 dirham=3.9g/3/4tsp] of

saffron, and water to cover the meat. Then take quince or apple, skin the outside and

clean the inside and cut it up in appropriate-sized pieces, and

throw them into the pot. Put it on a moderate fire [and cook it].

When it is done, take it away with a lid over it.

Cover it with breadcrumbs mixed with a little sifted flour and five

eggs, after removing some of the yolks. Cook it in the pot [over the

chicken]. When the coating has cooked, sprinkle it with rosewater and leave

it until the surface is clear and stands out apart. Ladle it out,

sprinkle it with fine spices and present it. This is given to feverish people as a food and takes

the place of medicine. Take sweet, peeled almonds and pound them fine. Then

extract their liquid with a sieve or clean cloth, until it becomes

like milk. Add pomegranate and tart apple juice, pear juice, juice

of quince and of roasted gourd, whatever may be available of these.

Prepare them with the "juice" squeezed from the almonds by adding

some white sugar. Put it in a glazed earthenware tinjir [pot] and light a

gentle fire under it. After boiling, add some dissolved starch

paste. [Stir.] When it thickens, put together rose oil and fresh oil

and cook on a gentle fire until it thickens. Then take it off the

fire and serve it. If the stomach is weak, add rosewater mixed with camphor. From the medieval cookbook of

Maestro Martino that I have here

on my site in old Italian, I have recipes that call for

quince: 'pome cotogne'. There is a similar recipe to the pudding

above, but Maestro Martino calls for more spices like ginger,

cinnamon and saffron, for a 'pome cotogne', quince, soup.] He also has a recipe for a wonderful quince

cheesecake. It is just like modern pumpkin cheesecake,

but the pumpkin puree is replaced by quince puree. Yummy! And he has a recipe for a savory pastry

quince snack pie. The pie crust is wrapped around a

half quince that is cored and filled with ground and spiced

meat. It is baked until the quince is soft. From the medieval cookbook by an

Anonymous Venetian that I have

here on my site in old Venetian, I have a recipe that calls for

quince, 'codogniato', and it is a quince jam and paste made with

honey instead of sugar, and with spices.

Adam and Eve's golden apple of knowledge was really a

quince. And the other apples mentioned in the Old and New

Testaments were certainly quinces.

Athena's golden apple of wisdom was really a quince.

The Greek goddess Hera's garden of the Hesperides, where her

immortality-giving quince were cultivated and protected by three

nymphs, was in Andalucía, the quince-growing capital of Spain.

Two Amazon.com books about Quince

"Simply Quince is the first tribute to the quince in culinary

history. Barbara Ghazarian masterfully presents the tree fruit’s

versatility, floral aroma, and unique flavor and color in 70 easy,

trendsetting recipes, full of legend, history, culture, and scientific

tidbits. Simply Quince contains a myriad of new ways to prepare quince

for both the formal and casual dining experience."

"Quince and fig must be the most romantic of all European fruits,

perhaps because they are among the oldest, perhaps because the luxury of

their perfume and texture provokes the most enthusiastic of responses in

the poetry and prose of Persia, of Greece, and of the West itself.

'The

Dutch author Ria Loohuizen has already written The Elder and The

Chestnut, published by Prospect Books, and here she offers the same

blend of history, anecdote, literary reference and recipes in respect of

the fig and the quince.

Because the quince has so particular and pungent

a flavour, anticipating in some ways the citrus fruits of the later

modern era, it was the precursor ingredient of many marmalades (the word

was indeed coined for the quince) and conserves. She therefore includes

a brief look at sugar in early-modern cookery as preface to a section on

quince pastes (of which the Spanish membrillo is the most famous modern

version).

'Her recipes range wider than Europe, including Persia to the

east and North Africa to the south, for the stamping grounds of these

fruits were far greater than merely the West. Some of them are truly

enticing: chicken with quince and walnut sauce; quince sherbet; Turkish

stuffed quinces; quince mostarda; savoy cabbage with fennel and quince;

anchovy and fig sauce with fried shrimp; stuffed figs with olive oil ice

cream; rabbit with figs; fig bread from the Maghreb; and fig tagine. "

Since Turkey is the world's largest cultivator of quinces, producing

half the world's cultivated quinces, it stands to

reason that they would have the most varied recipes for the quince.

Check out Binnur's Turkish

Cookbook site to see all the wonderful quince recipes online with

easy to follow recipes, both savory and sweet.

Search the site for the word 'quince' to see a list of the

quince recipes. The search box is in the right column a bit down

from the top of the main page.

Here are some mouthwatering images of some of the quince dishes.

Lamb-Quince Stew

Baked Quince with Cream

Quince-Nut Sweet Baked Dessert

And here is a

Moroccan recipe for a Quince Meat Stew

The Quince -

Mele cotogne, as old as the Mediterranean, and just as beautiful

![]()

Quince Puree

Marmellata di mele cotogne - Quince Jam

- Cotagnata - Dulce de membrillo

Quince Paste [quince jam and jelly]

Quince Paste

- Carne de membrillo

Chocolate or

Sugar Covered Quince Candies

Quince Meringue - Merengue di mele cotogne

This dessert looks classiest when made in individual portions, but

it tastes just as good in a large baking dish.

Quince

/ Apple Tart or Pie

Some more medieval Sweet and Savory Quince Recipes

Another Dish Which Strengthens the Stomach

A Dish of

Safarjaliyya, Good for the Stomach

Safarjaliyya

,

a Dish Made With Quinces

Safarjaliyya

,

a Quince Dish

Recipe for a Dish of Chicken or Partridge with

Quince or Apple

An Eastern Sweet [sweet pudding]