Candida Martinelli's Italophile Site

Main

Page This family-friendly site celebrates Italian culture for the enjoyment of children and

adults. Site-Overview

The

wonderful cookbook by food historian Donatella Cirri Martelli, La

vera cucina italiana (The True Italian Cuisine, Editoriale

Olimpia, 1980) provides entertaining and

edifying information on many Italian dishes and Italian cuisine in

general. If

you have the chance to get a copy of the book, I highly recommend it

for her erudition, passion for Italian cuisine, and her impeccable

Tuscan Italian. Below are summaries

of some of the information she includes, per section, along with a

few translated recipes. I've added other recipes from around

my site to this page, too. La

pasta asciutta - Dried Pasta La

pasta fatta in casa - Fresh Pasta (Homemade Pasta) Risotto,

Minestre, Zuppe, Polenta - Rice Dishes, Stews, Soups, Polenta Pizze,

Focacce, Torte salate - Pizzas, Flat

Breads (Pizza Breads), Savory Pies La

carne, Il pollo, Il pesce, Piccola salumeria casalinga

- Meat, Chicken, Fish, Homemade Cured Meats Le

verdure, La verdure sott’olio e sott’aceto, Le uova

- Vegetables, Vegetables preserved in oil and vinegar, Eggs I

dolci, I gelati, La frutta conservata, I liquori

- Desserts, Ices, Preserved Fruit, Liquors One

of the oldest of these recipes is for La panzanella, a

bread-based salad. It was

usually made with the week’s leftovers, because no food could afford

to be wasted. I usually

make it during the summer months, because it is delicious and

refreshing, and very easy to make. 500 grams of bread, preferably whole grain, and a few days old 4

very ripe tomatoes 2

red onions 4

tablespoons of olive oil 2

tablespoons of vinegar Chopped

fresh basil Salt and pepper to taste The

key to the dish is the soaking of the bread, diced, in cold water for

half an hour. Then you

wring it out with your hands and crumble it into a big mixing bowl.

Then you add the other ingredients, mix, and set it in the

fridge for at least two hours. She

includes a very old recipe for liver pate or Pasticcio freddo di

fegato, and explains that it has it’s origins in the Italian

Renaissance (Il Platina, again, and Cristoforo da Messiburgo in Banchetti,

composizione di vivande et apparecchio generale from Ferrara in

1549) when it was almost always used as filling for a meat pie. Only in the summer months was it used as a spread on bread or

crackers, as we use it today. 200

grams of veal liver (diced) 200

grams of chicken livers 100 grams of raw ham 120 grams of butter 1 egg yolk 1 tablespoon of cognac or aquavit 1 tablespoon of anchovies Sage leaves Two cloves of garlic Salt, pepper to taste Cook

the livers in 20 grams of the butter, and with the sage and the garlic

cloves. When they are done, put them in a mixing bowl and discard the

sage and garlic. Add the

ham, egg yolk, cognac and anchovies.

Mix well, then add the rest of the butter, softened, and mix

until you have a consistent cream of liver pate. Fett’unta

is as old as bread. It means 'bread-soaked', in olive oil.

Garlic bread as known outside of Italy, is not eaten in Italy.

Instead they make this recipe and it's variations, called Bruschetta. Bread

slices Extra

virgin olive oil Garlic

cloves Salt

and pepper Toast

the bread slices. Rub the

garlic cloves over the toasted bread.

They will dissolve into the bread.

Put the bread slices on a plate and season them with salt and

pepper. Then pour the

olive oil over them. Eat

while the slices are still crisp and warm. Variations: Prepare

the Fett’unta as described above, and then cover them with one or

more of the following toppings. Place

the bread slices in the oven for 5 to 10 minutes until the toppings

are melted or cooked. They

need less cooking time if you place the slices under a grill. Grated

or thinly sliced cheese of any kind Capers Thinly

sliced onion rounds Bits

or slices of meat of any kind Sliced

or minced mushrooms Fresh

or dried oregano, sage or rosemary Tomato

paste or sauce Cooked

beans in a sauce Thinly

sliced or diced vegetables

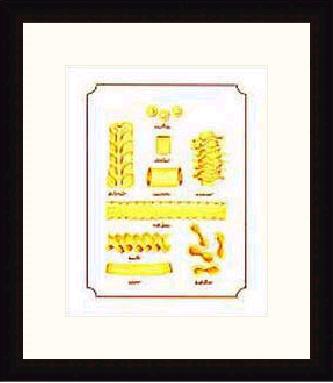

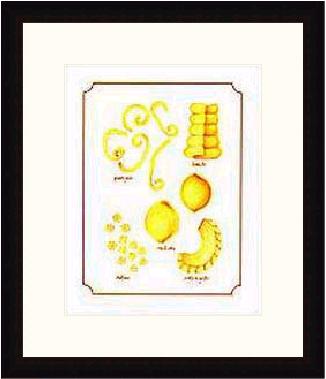

Even

though the old texts use the term lasagna, they actually refer

to something more like tagliatelle.

Spaghetti comes from the Napels region, and most regions have a

traditional pasta shape. Maestro

Martino’s De arte coquinaria from 1450 has recipes for vermicelli

and maccheroni. The

story of pasta coming from China is a myth. The

earliest seasonings for the cooked pasta were meat sauces, milk,

butter, cheese, vegetables, and only after the arrival of the tomato

from the New World, and then some time to be convinced it wasn’t

poisonous, did tomato find it’s ideal partner in pasta.

Practically every family in Italy has a favorite sugo or

salsa for their pasta, so I won’t waste time putting one

here. But I will put a

recipe for an older pasta sauce, originally Italian (with some

variation in ingredients) and now considered French:

La besciamella (white sauce).

The Medici called it colla, which means glue, and when

it cools it is very glue-like, but when it is warm it makes a rich and

exotic pasta sauce. 50

grams of butter 4

tablespoons of white flour ½

liter of milk or chicken broth (milk for vegetable pastas, half/half

for meat and fish pastas) 50

grams of grated Parmesan cheese Salt

to taste Grated

nutmeg Most

recipes have you melt the butter, then add the flour, and then slowly

whisk in the hot liquid. I

find that unnecessarily laborious and too often end up with balls of

flour. I never have a

problem when I start with cold liquid, whisk in the flour, then heat

it up slowly, whisking as it cooks.

After a low boil, whisking continually, for about 5 minutes, it

is usually ready. Remove

it from the heat and add the butter and cheese and stir until they

melt. Then add the salt

and nutmeg to taste. To

give you an idea of how much nutmeg you might use, I like a lot of

nutmeg, which usually means about ½ a teaspoon. Penne

are thick tubes of pasta about as long as your thumb.

They hold up well to strong flavors and retain their chewy

texture even when not served immediately.

Cook them according to the instructions on the package, which

should indicate the number of minutes they should be boiled in salted

water. Variations: Cream

and Ham Sauce:

Melt a few tablespoons of butter in a pot over a medium heat,

then add fresh cream and let it evaporate a bit on a high heat for at

least 5 minutes. Add

diced cooked ham, the cooked Penne, grated Parmesan cheese,

salt and pepper to taste. Let

it cook just a few minutes more, stirring continually.

Adjust the amounts of cream and ham to suit your personal

tastes and the amount of pasta the sauce is to cover. Cream,

Ham and Pea Sauce:

Cook the sauce as described above.

When you add the cooked Penne, add cooked peas to the

sauce as well. Cream,

Garlic and Mushroom Sauce:

Melt a few tablespoons of butter in a pot over a low heat and

add chopped garlic cloves to personal taste.

Cook for a few minutes, then add fresh cream and let it

evaporate a bit on a high heat for at least 5 minutes.

Add chopped, sautéed mushrooms and the cooked Penne,

and season with salt and pepper to taste.

Let it cook just a few minutes more, stirring continually.

Adjust the ingredient amounts according to your personal tastes

and the amount of pasta the sauce is to cover. Just

one last word, concerning the cold-water-on-cooked-pasta debate.

Ms. Martelli, in her authoritative voice, says that one cup of

cold water thrown over just cooked pasta, works well as a break on

cooking, long enough to get the pasta seasoned and served up at table.

But you should never rinse the cooked pasta under running water

because you lose the flour-water coating that has formed over the

pasta, which helps the seasonings cling to it.

In

Ferrara they also say that tagliatelle were made to imitate the

long blond hair of Lucrezia Borgia who married Alfonso I d’Este, the

Lord of Ferrara, in 1501 (her third ‘lucky’ husband).

It is from this period that tagliatelle were a part of

all the great banquets. Tomato

is added to pasta to make red pasta.

Spinach is added to make green pasta.

Ms. Martelli describes a patriotic tri-colore

(tri-color) dish that some people serve on patriotic occasions.

All three colors of tagliatelle are prepared, and then

they are seasoned with three different colors of sauces.

For example, on the serving dish you would see white pasta with

tomato sauce, the green pasta with white sauce (besciamella),

and the red pasta with a green sauce (pesto). To

make fresh pasta at home, one must have a pasta machine to create the

sheets, a rolling board, a rolling pin, patience, patience and more

patience. And as with all

artistry, practice makes perfect.

So the only recipe I’ll put here is one Ms. Martelli calls Gnocchi

di spinaci or malfatti alla fiorentina, because it requires

none of these things. It

is typically served during Lent. 1 kilo freshly cooked spinach, all moisture removed, chopped finely 500 grams of fresh ricotta cheese 200 grams of grated Parmesan cheese 2 large eggs, or 3 small ones Ground nutmeg (1/2 teaspoon or so) Salt to taste Mix

together the chopped spinach, cheeses, eggs, nutmeg and salt.

Shape small balls of the pasta, then lightly flour them.

Cook them in boiling water until they float.

Remove them and season them immediately and serve.

A simple seasoning is best, like melted butter with some sage

and Parmesan cheese. But

you can use a tomato sauce if you prefer. Ms.

Martelli reminds the reader that pasta is not the only first course

dish in Italian cuisine. It may be one of the most unique and best know abroad, but in

Italy, it is not a fixture at every Italian’s lunch. Alternating with pasta as first course are rice dishes

(risotti), polenta, and a wide variety of soups (stews, broths, soups,

cream-soups). Rice

dishes date from the twelfth century, having come from Chine via the

Silk Road, brought by traveling monks and planted in 1150.

It is easily cultivated in the Po Valley (Vermicelli, Lombardy,

Piedmont), and is the basis of many of the most famous northern first

course dishes (rice with just about every vegetable imaginable), and

desserts (for which the rice is cooked in milk).

Italian cuisine uses short-grain rice rather then the preferred

long-grain used in the Orient. Short-grain

rice absorbs more seasonings because of it’s glutinous

coating. It’s

tastier. Polenta

has an even older origin, if with various grains, dating from the

pre-Roman Etruscan period. However,

it is probably as old as the cultivation of grain itself, ten thousand

years old. It is the mainstay of many of today’s populations in the

poorest regions of the planet, especially made with sorghum, a grain

used by the Etruscans for their pultes, polentas. Grain

grows best in Italy’s northern regions (Veneto, Lombardy), and it is

here that polenta is most eaten.

But even the winter-cold central regions enjoy the dish,

usually served with hearty game sauces.

It can vary in color from grey to orange.

Before maize (cornmeal) was brought from the New World,

polentas in Italy were made from gran-turco (gran-saraceno) -

Durham Wheat, the grain that is used for couscous, a similar dish

eaten throughout North-Africa. Polenta

is eaten freshly cooked with a sauce poured over it, or sliced up

after it has cooled, and then baked in the oven with various

ingredients between layers of polenta slices.

The following is one such recipe. 300

grams of sliced, cooked polenta 100

grams butter, diced 100

grams of grated Parmesan cheese 100

grams of grated Gruviere cheese Besciamella

(see above) Layer

the polenta slices in a buttered dish, alternated with the other

ingredients. Make sure

you don’t finish with the polenta slices on top.

Then cook it in a hot oven for at least 10 minutes.

You can season it with sage or diced ham if you like between

the layers. Soups

have been the mainstay of the poor since the beginning of time.

The broth base can be made from leftover animal bones, and the

soup ingredients can be leftovers of meat, vegetables, and even bread.

The richer variety of soup, the cream-soups, date from the

Italian Renaissance. Interestingly,

the oldest Italian soups contain boiled bread, as it was the tradition

in the Middle-Ages to serve meals to the gentry on unleavened bread,

and then the servants boiled up all the leftovers, including these

early versions of pizzas, as their one meal of the day. Focacce

remained popular throughout the middle ages, and each region of Italy

made local versions, with local names. The

Latin dialects became the Italian dialects, and the names remained.

These are the various names used today in Italy for the

regional variations: focaccia,

cavaccino, pizza, pitta, impanata, calzoni, panzerotti, etc.

They are known around the world, but like all of Italian

cooking, there are few rigid rules about how to make them.

The individual creativity of the cook is encouraged.

In Italy, cooking truly is a creative outlet. 1

cup lukewarm milk 1

package yeast 1

tbsp sugar 1tsp

salt 3

tbsp olive oil Approx.

2 ½ cups flour In

a room temperature glass or crockery bowl, dissolve the yeast in the

milk, then mix in the sugar, salt, and oil with a wooden spoon. Add the flour until the dough forms a compact ball.

Roll out the dough to ¼ inch thick and place on an olive-oiled

oven tray. Press firmly

with your fingertips to make indentations in the dough.

Cover with a clean tea towel and let it rise to double in

height. This should take

only 1 hour if you keep the tray in a warm, draft-free place.

This is the basic Foccace dough.

Below are various toppings to add to the risen bread before it

is cooked in a hot oven for roughly 10 minutes, or until the crust is

golden. Toppings: Olive

Oil: Pour olive oil over the dough and spread it around with your

fingers to cover the entire surface.

Then sprinkle the dough lightly with salt. The fruitier the oil, the tastier the bread. Olive

Oil and Rosemary:

Prepare the dough with the previous topping and then sprinkle

it with chopped fresh or dried rosemary. Onion

and Cheese:

Cover the dough with cooked onions and then sprinkle with

grated cheese. Tomato:

Cover the dough with a tomato pasta sauce and then drizzle

olive oil over the top. Raisons: Add raisons to the dough just before you roll it out to rise.

After the rising, cover the dough with olive oil and salt as

described for the Olive Oil topping. One

of the classic savory pies is La torta Pasqualina, The Easer

Pie. The time before

Easter is Lent, when the Catholic church forbade the eating of meat

and eggs. So when Easter

came, ending the restrictions of Lent, it was customary to celebrate

with eggs dishes, also because eggs signify rebirth.

You find the same tradition in orthodox Christian customs, too.

This pie is from the Lombard region of Italy. Pie crust for a double-crust pie 400

grams of cooked and finely chopped spinach 300

grams of fresh ricotta cheese 6

eggs 100

grams of grated Parmesan cheese Parsley,

2-3 tablespoons Marjoram,

a pinch Sale

and pepper, about one teaspoon of salt and ½ of pepper Butter

a round casserole dish, then line it with the crust.

Mix together the spinach, cheeses, two eggs, parsley, marjoram,

and salt and pepper. Put

the filling in the crust. Then

use a spoon to form four pockets in the filling.

Put one egg in each, raw, but without the shell (different from

the Greeks who cook the eggs with the shells in Easter breads!).

Then put the top crust on, seal it, brush it with olive oil. Cook it in a moderate over for roughly an hour and ½.

If the top cooks too quickly, cover it with aluminum foil.

It is best eaten warm or cold, but never hot. Romans

prided themselves on their dietary frugality, and ate meat rarely

during any week. When they did eat meat, it was not beef, cows and bulls being

too valuable in agriculture and the production of milk. They ate pork, chicken and wild fowl (that too has

disappeared after the flood-plains were drained).

Slaves, over half of the Roman-era population, lived on bread,

olive oil, olives, rotten fruit, and the leftovers from their

master’s table. The

middle-ages saw a worsening of diets due to the continual wars and the

insecurity economic depression that accompanied them.

Only when the Renaissance began, did the diets of the poor

improve, but while the rich ate the best parts of the beasts, the poor

had to make due with the internal organs and the ears and feet of the

animals. They created

tasty dishes that entered Italian cuisine and are still eaten today.

(The internal organs of animals butchered in the U.S. are often

shipped to Europe for sale.) I won’t put one of those recipes here, mainly because the

smell of them turns my stomach (sorry, but it’s the truth). Instead, here’s a recipe from Northern Italy. 400

grams of chicken breasts, pounded into thin fillets 400

grams of sliced mushrooms ¼

liter of cream 50 grams of butter 50

grams of flour 2

cloves of garlic, crushed salt

and pepper to taste Melt

the butter in a pan and add the garlic.

When the garlic is toasted, remove it.

Then lightly flour the chicken breasts and brown them on both

sides in the hot butter. Add

the mushrooms and cover the pan to let them cook for 10 minutes.

Then uncover the pan and raise the heat to cook off some the

mushroom liquid. Then add

the cream and cook, stirring for 10 minutes until you have a nice

thick sauce. Season to

taste with salt and pepper. (Ms.

Martelli has you add 1 teaspoon of lemon juice to the cooking

mushrooms, and season the dish at that time.

It is up to you.) Grilled

meats are very popular and the best restaurants for freshly grilled

meats are the special Grillaio restaurants that grill everything

(except the pasta!). I always seemed to find them in the

mountain villages, and you can smell them as you approach. The

wonderful aroma of the charcoal and cooking meats is their best

advertising. Pollo

alla griglia - Grilled Chicken Medium-sized

pieces of chicken either on the bone or not Vinegar

or lemon juice Crushed

garlic cloves Herbs Marinate

the chicken pieces several hours, preferably overnight, in the

vinegar/lemon juice, garlic and herbs.

The vinegar/lemon juice tenderizes the meat, and the meat takes

the flavors of the garlic and various herbs.

After marinating, dry the chicken pieces then coat them with

olive oil, and grill. Season

with salt and pepper as it cooks. Italians often use large pieces of

sage or rosemary dipped in olive oil to brush the meat as it grills to

add flavor, and to apply the oil which makes the meat crisp and brown.

The marinade should be used only to tenderize and flavor the

raw chicken, not for basting or as a sauce for sanitary

reasons. Variations: The

variations are in the herbs that you use in the marinade, or the

liquids you add for flavor. Try

various combinations to find the ones that appeal to your personal

tastes. Here are some

suggestions. Fresh

or dried sage Fresh

or dried rosemary Fresh

or dried thyme Extra

crushed garlic cloves Orange

juice Whisky,

vodka or other strong liquor Fish

has always been a staple of the Mediterranean diet, but pollution has

killed off most of the fresh water fish in Italy, and the

Mediterranean is considered, technically, a dead sea.

The result has been higher fish prices, just as the prices of

meat has come down. Even

the fish that does appear on the market is often of questionable

quality due to pollution in the seas where they are fished or farmed.

Sadly, this is not a problem unique to Italy.

The following is the simplest way to cook a fish, and if the

fish is fresh, it is the tastiest, in my humble opinion. 1

whole fish, cleaned (especially nice with trout and salmon-trout) several

cloves of crushed garlic One lemon sliced thinly 1

cup of chopped parsley Salt

and pepper to taste Set

the fish on a sheet of aluminum foil large enough to wrap it up.

Fill the fish with the garlic and parsley.

Put lemon slices inside and outside the fish.

Seal it in the foil and set it in a hot oven (on a tray is

you’d like, to catch any escaping juice) for 20 minutes or 30

minutes for a thick fish. Remove

it from the oven and foil, season with salt and pepper, and serve.

Or you can serve it and let each person season it to their

taste. Vegetables

have always been a large part of the diet of the people living on the

Italian peninsula, not only because many varieties grow wild, there,

but because their nutritive and medicinal qualities have long been

known. Potatoes

arrived from the New World in the 17th century, and quickly

became a staple of the diet of Northern Italians, especially those

living in the mountains. This

manner of cooking potatoes is the tastiest fried potatoes I’ve ever

eaten. And whatever you

do, don’t call the French Fries. Two

medium-sized potatoes per person, sliced into strips about ½ inch

thick Two

cloves of garlic, sliced in two with the skin on, if you’d like Peanut

oil (this is the best oil for frying because it can reach higher

temperatures without burning) Salt

and pepper Put

the oil in a pot and heat it up.

It is best to put it in a deep pot rather than a shallow pan.

Add the garlic and when they start to brown, the oil is

generally ready. Add the sliced potatoes, but only enough that they still have

room to float around a bit. It’s

best to cook several batches than try to cook them all at once,

because water escapes during the cooking process, and it can make the

potatoes stick together. I

like to remove the garlic when it is thoroughly cooked to avoid a

burnt taste getting in the oil. Add

some salt and pepper while the potatoes are cooking.

I decide they are done, when I think they are golden enough,

and then I wait one more minute.

They never seem to be done when I think they are, so that one

minute makes all the difference in the world.

Remove the potatoes from the oil with a strainer tool and let

them sit on paper towels for a few minutes.

Season them further now, and serve while they are still hot. Melanzane,

or egg plant, is a typical vegetable of Southern Italy because of the

warm weather needed to grow them, and because they were brought there

by the Arabs who ruled over that region for a time.

The name even comes from the Arab word for the vegetable badingian. Pepperoni,

or sweet bell peppers, are another vegetable typical of Southern

Italy, again because of the warm weather needed to ripen them, and

because the Spanish brought them there, from Brazil, when they ruled

over both regions. Greens,

like spinach, grow wild throughout Italy.

They are especially nice in this following recipe, but you can

make this dish with many other kinds of vegetables like cooked

broccoli, cauliflower, and carrots.

It’s name, sformato, means ‘misshapen’, which

I’ve always imagined referred to how the vegetables are chopped up

before cooked into a new form. It

is a simple, yet exquisitely tasting dish, that seduces even men, who

seem to have a natural aversion to vegetables. 300

grams of cooked spinach, chopped very finely Besciamella,

prepared as reported above 40 grams of butter 2

egg yolks Salt

and pepper, about 1 teaspoon salt and ½ teaspoon of pepper A

pinch of nutmeg, about ¼ teaspoon 100

grams of grated Parmesan or Gruviere cheese Mix

together the spinach, besciamella, then add the egg yolks, salt

and pepper, nutmeg and almost all the cheese.

Butter and flour a baking dish.

Put in the mixture and flatten it out.

Drop pieces of the butter over the top and sprinkle it with the

leftover cheese. Set it

in a hot oven for 10 to 15 minutes, until it is firm and golden.

It is delicious warm and cold, as a side-dish, and as a

vegetarian dish. It is

even nice sliced and served between bread as a sandwich. Mushroom

dishes abound in Italy, mainly because they grow wild there.

For this reason, Italian mushroom recipes are best when made

with wild mushrooms or the expensive Porcini mushrooms. The

ancient Greeks and Romans enjoyed finocchi, or finocchio

in the singular form, just as much as today’s Italians.

It’s anisette taste is quite strong when eaten raw in a

salad, but it become milder and more refined when cooked.

It can be cooked in just about any way you can imagine:

boiled, fried, baked, sautéed, grilled. Artichokes,

carciofi, are native to the Mediterranean basin, and have been

part of the Italian diet for their flavor as well as for their

medicinal properties. To this day, digestives are made from distilled artichokes

for their supposed purifying properties for the liver and kidneys. However, the scientists now say you get that effect eating raw

artichokes only. My

favorite Italian vegetable is the Zucchino. It is

delicious in a variety of ways, as are all vegetables in Italy.

You can use these same guidelines for almost any vegetable. Grilled: Slice

the zucchine into chunks or lengthwise into strips. Place them in an oven dish and add a few spoonfuls of olive

oil. Mix the pieces until

they are thinly coated with the oil.

Set under a hot grill for roughly 10 minutes, turning the

zucchine occasionally. Season

with salt and pepper as it cooks. Fried: Slice

the zucchine into chunks or lengthwise into strips. Sprinkle the pieces with salt and let them sit 30 minutes to

remove excess water. Rinse,

and then dry the pieces. Dip

them in a batter of egg yolks, flour, salt and pepper.

Cook them in hot vegetable oil until golden, then remove and

drain on absorbent paper. Serve

hot. Sautéed: Dice

the zucchine. Heat olive

oil, enough to cover the bottom of the pot, and add crushed garlic. Add the zucchine and cook over a medium heat, stirring

occasionally, until the zucchine is soft, roughly 10 minutes. Season with salt and pepper as it cooks. Salad: Boil the zucchine whole for roughly 10 minutes,

or until a fork enters it easily.

Remove and cool. Dice

the zucchine and mix it with other cooked and diced vegetables such as

potatoes or carrots. Season

with olive oil, vinegar or lemon juice, salt and pepper, basil or

oregano or mint, and anchovies if desired.

Vegetables

are often cured in oil or vinegar, the most famous of these is of

course the olive, the basis of the ancient Mediterranean diet.

But all other vegetables are preserved in this way, too, and

used as antipasti, or mixed into salads. The

frittata is a fried egg dish that is very versatile.

You can cook it with almost any combination of herbs,

vegetables, with fresh cheese, or as the Neapolitans, cook it over

leftover spaghetti. The

trick is in the beating of the eggs, and in flipping it over. Estimate

one egg per person, plus one for the meal (for example, for 4 people,

you would use 5 eggs). Separate

the eggs and beat the whites first, with a pinch of salt and pepper,

until they are frothy. Then

add the yolks. It’s

best to use a heated non-stick pan with high edges, lightly oiled.

Pour in the egg mixture and let it cook for several minutes

until it is set on the bottom, but still raw on top.

Use the lid of the pan, or a large plate, to help you turn the frittata

over, to cook the other side. Place

the lid over the pan, and turn it over.

The frittata will fall on the lid.

Put the pan back on the fire, and let the frittata slide

back into the pan, the raw side down.

Let it cook a few minutes more, then serve topped with a bit of

melted butter, and grated Parmesan cheese. Ancient

Rome loved its sweets, many made with fruit, and sweetened with

honey or a syrup made from grapes.

The sweets made in Italy today have precedents in Rome, such as

cooked fruit dishes, honey and almond candies, strudels, biscuits,

sweet breads, marmalade, and puddings. It’s

during this time that the Arab sharbat became the Italian sorbetto,

made with wine, honey and fruit, and chilled first with the perennial

glaciers on Mount Etna in Sicily, and later in ice cellars, like the

one constructed under Palazzo Pitti in Florence by the Medici, just

for their gelati. It

was during the time of the Medici that sorbetti became gelati

by adding milk and eggs to the ingredients. By

the 1400s recipes can be found for baked custards, cheese cakes, rice

puddings, rice tarts, fried dough pastries.

Regional diversification of sweets is also a product of this

time. The Southern

Italian regions held closely to the Arab sweets traditions, while the

Northern Regions embraced sweets made with cream, pastries, butter and

fruit. Desserts

served after a meal are usually for special occasions.

It is more usual to end a meal with fruit, nature’s candy,

you could say, than with a baked sweet.

For this reason, many Italian sweets are linked to holidays or

seasons. Check

my creams-puddings, spoonbreads, and granita

pages for recipes. On my Liqueur

page there are recipes for my Zabaione and Vov, a Zabaione liqueur,

and for a coffee liqueur. But

here I’ll put a recipe for one of my favorite Italian sweets, the crostata,

or tart. Here are

recipes, from my e-book, for the crust and some classic fillings. ½ cup flour ½

cup melted butter ¼

cup sugar 2

egg yolks 1

tsp grated lemon rind 1

tsp sweet dessert wine (such as Marsala or Vin Santo) Mix

the butter with the flour. Add

the sugar, egg yolks, wine, and the lemon rind and work it quickly

into a dough. Form the

dough into a ball, wrap it in waxed paper and place it in the

refrigerator for at least 1 hour.

Remove, roll out, and fit into the tart pan. Use all the dough, folding the sides in to make a thick edge

to the thick crust. Crostata

di marmelata - Jam Tart:

Spread the jam of your preference over the dough.

For a richer flavor, you can mix into the jam 1 tbsp of cognac

or another liquor. For this tart, reserve some of the dough and roll it into

thin logs. Place these in

a grid pattern over the jam. Brush

them with beaten egg. Cook

the crostata for approximately 15 minutes at a moderate temperature

until the crust is golden. Cool. Crostata

di limone - Lemon Tart:

Mix together 2 eggs, 1 cup powdered sugar, 3 tbsp lemon juice,

1 grated lemon rind, ½ tsp salt, 3 tbsp flour.

Pour into the crust and bake approximately 15 minutes at a

moderate temperature, or until the filling is firm.

Cool. Crostata

di ricotta - Cheese Tart:

Mix together until creamy 1 cup of ricotta cheese, ¼ cup

sugar, 2 tbsp cream if needed to make a creamy texture.

Then add two eggs (you can whip the whites and fold them in

last, for a lighter texture), the juice and grated rind of one lemon,

½ tsp salt. Put in the

crust and bake approximately 15 minutes at a moderate temperature, or

until the filling is firm. Cool.

Salame Dolce - Sweet Salami This traditional Tuscan recipe is called Sweet Salami

because it's made to look like a salami. It's actually a delicate, refined, chocolate candy. It's embarrassingly simple to make. It looks wonderful served on a special occasion. It tastes great with a cup of coffee or tea, instead of a

cookie/biscuit or piece of cake. Ingredients: Instructions:

Zabaione - Sabayon

Ingredients: 6

eggs yolks 3/4

cups sugar 1

cup Marsala wine Instructions: Put

the yolks and sugar together in a stainless steel pot. Mix

this with an electric mixer over a very low heat (or in a

double-boiler) constantly as you slowly add the Marsala wine. Cook

it for at least 5 minutes, mixing all the time as it thickens. If it's not

light and airy after that, whip it for another few minutes at high

speed. (Cooking times vary so be patient. It's the egg

yolks that do the most to thicken the dessert, so if the eggs are

small, add an extra yolk.) Serving

Suggestions: It's delicious

served warm over sliced fruit, especially peaches. Traditionally,

it’s served with cookies. Fancy

restaurants serve it warm in a brandy snifter with a long handled

spoon. 6 egg yolks 500 grams of sugar 1/2 liter of whole milk 1/2 liter of Marsala wine 1 lemon 1-2 teaspoons of Vanilla

extract Put the yolks and sugar together in a pan. Mix this with an

electric mixer over a very low heat (or in a double-boiler) constantly

as you add the Marsala wine. Cook it for at least 5 minutes,

mixing all the time. Then slowly add the milk and cook, stirring

with a wooden spoon, for 5 minutes. Remove from heat and add the

juice of the lemon, and the Vanilla extract. You can drink it right away, or store it in the refrigerator,

pretty much for as long as you'd like, but don't exaggerate. Trust

me, once your family tastes it, it won't last long. Just like the

commercial Vov, it's great in coffee, over ice cream, in cakes and

icings, and even the new way in cocktails.

Liquore di caffe -

Coffee Liqueur The sugar and water base in this recipe is the syrup for any sweet

liqueur, and you can add as much alcohol as you want (alcohol preserves

it, so be sure to put enough to keep it safe from germs). You can

experiment by adding fruit syrups to flavor the liqueur any way you

want. Here's the coffee version. 2 cups water 2 cups sugar 1/2 cup good quality instant

coffee 1-2 teaspoons Vanilla extract

(to taste) 1 1/2 cups Vodka Boil the water and sugar until the sugar is dissolved. Remove

it from the heat. Dissolve the coffee in the Vodka. Add the

Vanilla. Then add this to the syrup. Mix

carefully. You can use it immediately, or store it in air-tight

bottles. It thickens as it cools. It's delicious over ice

cream, added to coffee or milk, or on it's own. A drop of cream

sets a serving off well.

Recipes

and Italian Food History

![]()

The

True Italian Cuisine and Recipes

The

True Italian Cuisine and Recipes

Gli

antipasti - Appetizers

Antipasto

comes from Latin, meaning ‘before a meal’, but in Italy is meant

as a stuzzichino, or taste of foods that stimulate the

appetite, preparing it for the full meal.

The same recipes are used for tramezzi or piatti di

mezzo, a classic tradition of serving tasty morsels between main

dishes. Today they are

often used at receptions that require finger-food, or for light summer

meals.

Antipasto

comes from Latin, meaning ‘before a meal’, but in Italy is meant

as a stuzzichino, or taste of foods that stimulate the

appetite, preparing it for the full meal.

The same recipes are used for tramezzi or piatti di

mezzo, a classic tradition of serving tasty morsels between main

dishes. Today they are

often used at receptions that require finger-food, or for light summer

meals.La

panzanella - Bread Salad

Ms.

Martelli explains that la maionese, used in some antipasti

recipes, while it is clearly an Italianization of the French word for

mayonnaise, it actually has older roots in Italian cuisine than in

French cuisine. Il

Platina describes a recipe in his 1475 cookbook for a sauce made with

eggs with lemon juice that is very similar to modern mayonnaise.

Ms.

Martelli explains that la maionese, used in some antipasti

recipes, while it is clearly an Italianization of the French word for

mayonnaise, it actually has older roots in Italian cuisine than in

French cuisine. Il

Platina describes a recipe in his 1475 cookbook for a sauce made with

eggs with lemon juice that is very similar to modern mayonnaise. Pasticcio

freddo di fegato

- Cold Liver Paste

La

pasta asciutta - Dried Pasta

The

history in Italy of dried pasta cooked and seasoned with a sauce can

be traced as far back as the Etruscans (900 B.C.) who seasoned their

pasta with game (venison) based sauces.

This passed on to the Romans and then appears in the first

Italian cookbook in Italian, rather than Latin, by Anonimo Toscano,

from the end of the 1300’s, and published for the first time in 1963

by Francesco Zambrini. The

pasta was cooked in broth and seasoned with cheese.

The

history in Italy of dried pasta cooked and seasoned with a sauce can

be traced as far back as the Etruscans (900 B.C.) who seasoned their

pasta with game (venison) based sauces.

This passed on to the Romans and then appears in the first

Italian cookbook in Italian, rather than Latin, by Anonimo Toscano,

from the end of the 1300’s, and published for the first time in 1963

by Francesco Zambrini. The

pasta was cooked in broth and seasoned with cheese. La

besciamella

- Béchamel or White Sauce

La

pasta fatta in casa - Fresh Pasta (Homemade Pasta)

Fresh

pasta is made in sheets and cut and shaped in the various types of

pasta. It’s said that lasagna

and tagliatelle, and pasta filled with pumpkin (the earliest

fillings) are all from Ferrara. And

cappelletti, ravioli and cannoli (not the dessert cannoli) are

from Modena.

Fresh

pasta is made in sheets and cut and shaped in the various types of

pasta. It’s said that lasagna

and tagliatelle, and pasta filled with pumpkin (the earliest

fillings) are all from Ferrara. And

cappelletti, ravioli and cannoli (not the dessert cannoli) are

from Modena. Gnocchi

di spinaci / malfatti alla

fiorentina - Spinach Gnocchi / Florentine Misshapen Things

Risotto,

Minestre, Zuppe, Polenta - Rice Dishes, Stews, Soups, Polenta

Polenta

pasticciata

- Polenta Pie

Pizze,

Focacce, Torte salate - Pizzas, Flat Breads (Pizza Breads),

Savory Pies

Throughout

the Mediterranean basin flat breads made of ground grains mixed with

water have been staples of the diet for centuries.

The Phoenicians, Mediterranean traders from what is now

Lebanon, passed the custom on to the people of Carthage, who were

famous for cooking focacce (risen flat breads) in terracotta

molds in the shape of flowers, fish and birds.

Greeks and Romans also used flat unrisen bread as plates,

serving the food on them, but not eating them.

Metal plates finally took the place of these mensae only

in the 14th century.

Throughout

the Mediterranean basin flat breads made of ground grains mixed with

water have been staples of the diet for centuries.

The Phoenicians, Mediterranean traders from what is now

Lebanon, passed the custom on to the people of Carthage, who were

famous for cooking focacce (risen flat breads) in terracotta

molds in the shape of flowers, fish and birds.

Greeks and Romans also used flat unrisen bread as plates,

serving the food on them, but not eating them.

Metal plates finally took the place of these mensae only

in the 14th century.  Savory

pies (torte salate) are so-called to differentiate them from

dessert tarts. Like in all European cooking cultures, the pie is very old.

In ancient English texts, the crusts (top and bottom) are

called the ‘coffin’, because of the apt comparison with burials,

the food ‘entombed’ and cooked in the oven. Recipes for savory pies appear in the oldest Italian

cookbooks, often with the popular ingredients of the day:

cinnamon, sugar, almonds and rose water.

Savory

pies (torte salate) are so-called to differentiate them from

dessert tarts. Like in all European cooking cultures, the pie is very old.

In ancient English texts, the crusts (top and bottom) are

called the ‘coffin’, because of the apt comparison with burials,

the food ‘entombed’ and cooked in the oven. Recipes for savory pies appear in the oldest Italian

cookbooks, often with the popular ingredients of the day:

cinnamon, sugar, almonds and rose water. La

torta Pasqualina -

The Easter Tart

La

carne, Il pollo, Il pesce, Piccola salumeria casalinga - Meat,

Chicken, Fish, Homemade Cured Meats

In

her discussion of the history of meat in the diet of ancient Italians,

Ms. Martelli reveals something interesting.

There are those who believe the name given to the boot-shaped

peninsula, Italia, came from the word vitulia, which means the

‘land of veal’. It

was called thus because of the massive herds of beasts that roamed the

land. Etruscans, early

inhabitants of Italy, were famous as big meat eaters.

Eventually, these wild herd were depleted (just like the

forests that covered Southern Italy, which were cut down to build

Greek ships, leaving the soil to erode into the impoverished land that

remains today).

In

her discussion of the history of meat in the diet of ancient Italians,

Ms. Martelli reveals something interesting.

There are those who believe the name given to the boot-shaped

peninsula, Italia, came from the word vitulia, which means the

‘land of veal’. It

was called thus because of the massive herds of beasts that roamed the

land. Etruscans, early

inhabitants of Italy, were famous as big meat eaters.

Eventually, these wild herd were depleted (just like the

forests that covered Southern Italy, which were cut down to build

Greek ships, leaving the soil to erode into the impoverished land that

remains today).Petto

di pollo con panna e funghi

- Chicken breasts with cream and mushrooms

Oven

Roasted Fish in Foil

Le

verdure, La verdure sott’olio e sott’aceto, Le uova -

Vegetables, Vegetables preserved in oil and vinegar, Eggs

Le

verdure, La verdure sott’olio e sott’aceto, Le uova -

Vegetables, Vegetables preserved in oil and vinegar, EggsPatate

fritte - Fried Potatoes

Tomatoes

came from the New World, too, and were found to grow best in the South

of Italy, especially around the Naples area, where even today they

produce the most, and best, tomatoes in the country.

Ms. Martelli says that tomatoes appear in 80 percent of all

Italian recipes, but that sounds a bit exaggerated to me.

Tomatoes

came from the New World, too, and were found to grow best in the South

of Italy, especially around the Naples area, where even today they

produce the most, and best, tomatoes in the country.

Ms. Martelli says that tomatoes appear in 80 percent of all

Italian recipes, but that sounds a bit exaggerated to me.Sformato

di spinaci - Misshapen Spinach Pie

Beans,

despite having arrived in Italy via the New World in the 16th

century, are an integral part of Italian cuisine.

A relative of the black-eyed pea has always been eaten,

especially in Tuscany. They are used in soups, salads, and eaten on their own, most

often with a dollop of olive oil over the top.

They are a delicious winter food, warming you up for hours.

Beans,

despite having arrived in Italy via the New World in the 16th

century, are an integral part of Italian cuisine.

A relative of the black-eyed pea has always been eaten,

especially in Tuscany. They are used in soups, salads, and eaten on their own, most

often with a dollop of olive oil over the top.

They are a delicious winter food, warming you up for hours.Frittata

semplice - Simple Frittata

I

dolci, I gelati, La frutta conservata, I liquori - Desserts,

Ices, Preserved Fruit, Liquors

The

middle ages saw a greater influence of Arabic sweets introduced in

Sicily and then quickly spread throughout the peninsula.

These are the unleavened sweets that are often a nougat holding

together nuts and candied fruit.

Sweet breads were also popular, often cooked with raisons and

fruit.

The

middle ages saw a greater influence of Arabic sweets introduced in

Sicily and then quickly spread throughout the peninsula.

These are the unleavened sweets that are often a nougat holding

together nuts and candied fruit.

Sweet breads were also popular, often cooked with raisons and

fruit.  Crostata

Crust -

Tart Crust

Crostata

Crust -

Tart Crust

![]()

![]()