Candida Martinelli's Italophile Site

Main

Page This family-friendly site celebrates Italian culture for the enjoyment of children and

adults. Site-Overview

Some of the most impressive images of Vesuvius erupting are photographs from it's

last eruption in 1944. The U.S. military had retaken the area

from the Nazi's, so the military photographers were on hand to

photograph the event. The lava flows were slow-moving, so

few

lives were lost, but homes and villages were destroyed.

Many images of Vesuvius's eruption in 1944 Although Mount Vesuvius erupts regularly in geological terms, it's the

eruption in

the year 79 that fascinates people the most. That's because

the time-capsule-like remains of the Roman towns of Pompeii and

Herculaneum, both devastated by the 79 eruption, have been

attracting visitors since their discovery in 1738 (Herculaneum)

and 1748 (Pompeii). And historians relive the year 79 eruption by reading a detailed

account of of the 19 hour eruption of ash, rock and pyroclastic

flows that the Roman politician and early naturalist Pliny the

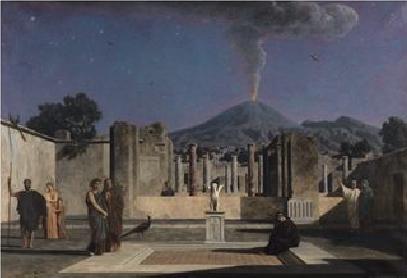

Younger recorded. An artist made this evocative depiction of the eruption, with the

Roman town awaiting it's doom from the approaching lava flows. This actual photograph from today shows how close the artist got

to what probably took place in 79 A.D. Pliny's uncle, Pliny the Elder, went by ship to get a closer view

of the eruption, and to assist in the rescue of survivors from the

shore. But he never returned. He died while sheltering on

shore from the rain of stones and ash, perhaps from a stroke or

heart attack. Over the years, the year 79 eruption has captured the imaginations of scientists, artists

and the public alike. Tourists to Italy have always

made Pompeii a must-see stop on their tours. I report below an abridged account by the writer William Dean

Howells of his return visit in 1908 to Pompeii after a first visit

in 1864 on his honeymoon. He gives a very good impression of

what Pompeii, and Italy, was like back then. He also

quotes from an Italian guide book of the period, translated into

dubious English. Pompeii and Herculaneum together had populations of perhaps

25,000. It's believed that at least 1500 people died in the

towns from the 79 eruption, but the number may well be greater.

The earthquakes that preceded the eruption, and the long eruption

process gave most people plenty of time to leave before the fatal

flows arrives at the towns. Pompeii is unique because it's a Roman town that has not been

altered since the Roman period. Other Roman towns have

continued to be lived in, and changed over the years. In Pompeii we can see things that help us imagine, as the art

below shows, just how things looked back in the year 79. The major roads with shops lining them, and homes above the

shops, and the major market area. The forum, auditoriums, and police/soldier barracks. Public and private baths. Shops, restaurants, hotels, modest homes, vacation villas. Schools, graffiti, advertising slogans, beware-of-dog signs, and

their love of their pets, things that make the people of the ancient

Roman empire seem human. And we can see lots of evidence of pagan worship combined with

the Mediterranean wide phallic worship. This phallic worship can still be seen today throughout the

Mediterranean region in the

phallic statues readily available at tourist centers, and in the attachment to representations of bull's

horns on chains around young men's necks. Pompeian home decor, as it was uncovered, influence European home

decor. Books were compiled of Pompeian designs for homeowners

to copy, some of which appear reproduced on this page.

Pompeian fashions influenced modern fashions. Jewelry and hair styles were copied. Gardens and villas were emulated. It's hard to overplay the influence of the discovery of Pompeii

on the arts of Europe, and in the minds of Europeans, but it

requires a study of it's own, and this page is just an introduction

to the subject. If you want to read more on the web about Pompeii, the Wikipedia

article on Pompeii

contains a lot of information and many links to interesting Pompeii

sites. And this is the

official website for the archeological site. But I highly recommend a site set up by the

Cole Family

who lived near Pompeii for work, and took an especial interest

in it. Their site is wonderfully informative, illustrated, and

interesting, and from a refreshingly Christian perspective on that

pagan period, adding greater understanding of life in Pompeii. Below you can

find some books about Pompeii from

Amazon.com. The BBC recently produced a television film about Pompeii, and

made

this site to accompany it. Here are some Pompeii DVDs.

Here following are images from 1890 of Pompeii. And after the images, you'll find an account by a tourist from

that same time period, the journalist and novelist William Dean

Howells.

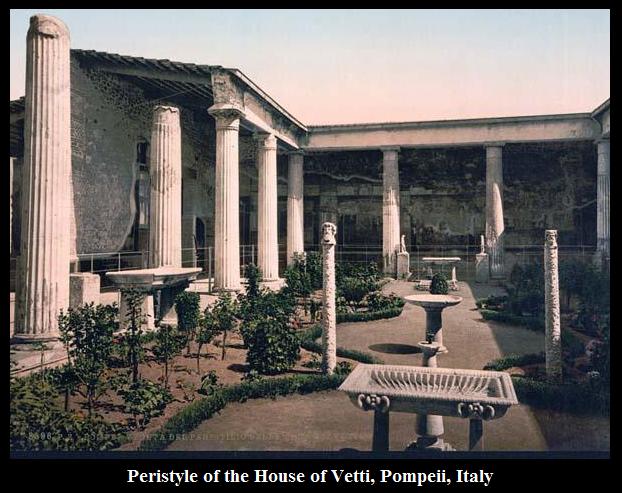

This colorchrome image is from 1890 showing how

the House of Vetti Peristyle looked at that time, about the time of

the account below by William Dean Howells.

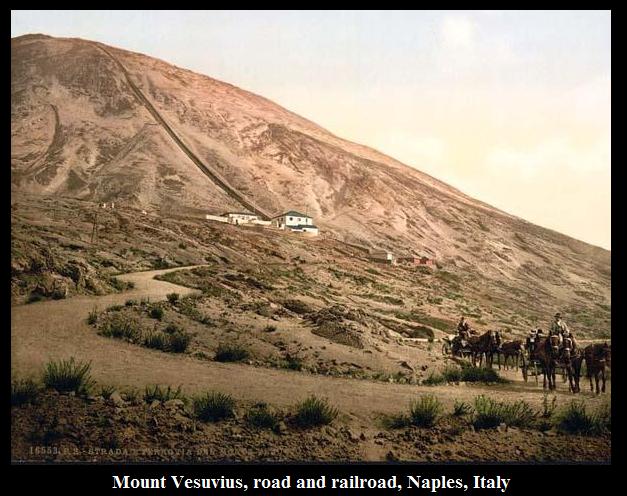

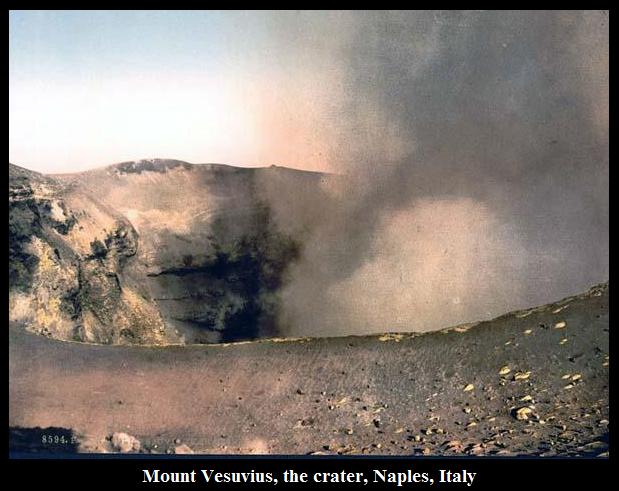

Tour guides would take people up to the crater of the volcano.

These extraordinary images come from the

Old Picture site. It

is a wonderful place to browse the past. If you are an

educator, it is a fantastic resource for lessons, bringing the past

to life in a way mere words or paintings cannot. This is the

link to

their Italy category, and this

link is to their home page. The country

through which we made the hour's run [ed. by train] was sympathetically squalid. We

had, to be sure, the sea on one side, and that was clean enough; but

the day was gray, and the sea was responsively gray; while the earth

on the other side was torn and ragged, with people digging manure

into the patches of broccoli, and gardening away as if it had been

April instead of January. There were shabby villas, with stone-pines

and cypresses herding about the houses, and tatters of life-plant

overhanging their shabby walls; there were stucco shanties which the

men and women working in the fields would lurk in at nightfall. At

places there was some cheerful boat building, and at one place there

was a large macaroni manufactory, with far stretches of the product

dangling in hanks and skeins from rows of trellises. We passed

through towns where women and children swarmed, working at doorways

and playing in the dim, cold streets; from the balconies everywhere

winter melons hung in nets, dozens and scores of them, such as you

can the Italian fruiterers' in New York, and will keep buying

when once you know how good they are. In Naples they sell them by

the slice in the street, the fruiterer carrying a board on his head

with the slices arranged in an upright coronal like the rich,

barbaric head-dress of some savage prince. Our train was

slow and our car was foul, but nothing could keep us from arriving

at Pompeii in very good spirits. The entrance to the dead city is

gardened about with a cemeterial prettiness of evergreens; but,

after you have bought your ticket and been assigned your guide, you

pass through this decorative zone and find yourself in the first of

streets where the past makes no such terms with the present. Most of the

places I re-entered through my recollection of them, but to this

subjective experience there was added that of seeing much newer and

vaster things than I remembered. That sad population of the victims

of the disaster, restored to the semblance of life, or perhaps

rather of death, in plaster casts taken from the moulds their decay

had left in the hardening ashes, had much increased in the

melancholy museum where one visits them the first thing within the

city gates. The identity of each of the public

edifices is easily attested to the archaeologist, but the generally

intelligent, as the generally unintelligent, visitor must take the

archaeologist's word for the fact. One temple is much like another

in its stumps of columns and vague foundations and broken altars.

Among the later discoveries certain of the public baths are in the

best repair, both structurally and decoratively, and in these one

could replace the antique life with the least wear and tear of the

imagination. I could not

tell which the several private houses were; but the guide-books can,

and there I leave the specific knowledge of them; their names would

say nothing to the reader if they said nothing to me. In Pompeii,

where all the houses were rather small, some of the new ones were

rather large, though not larger than a few of the older ones. Not

more recognizably than these, they had been devoted to the varied

uses known to advanced civilization in all ages: there were

dwellings, and taverns and drinking-houses and eating-houses. The pictures

on the walls of the newly excavated houses are not strikingly better

than those I had not forgotten; but of late it has been the purpose

to leave as many of the ornaments and utensils in position as

possible. The best are, as they ought to be, gathered into the

National Museum at Naples, but those which remain impart a more

living sense of the past than such wisely ordered accumulations; for

it is the Pompeian paradox that in the image of death it can best

recall life. There is no Elevated or

Subway at Pompeii, and even the lines of public chariots, if such

they were, which left those ruts in the lava pavements seem to have

been permanently suspended after the final destruction in the year

79. We were not

only very tired, but very hungry, and we asked our guide to take us

back the shortest way. He acted upon it instantly, and we cut across the back

yards and over the kitchen areas of several absent citizens on our

way back. Our guide was as good and true as it is in the nature of

guides to be, but absolute goodness and truth are rather the

attributes of American travellers; and you will not escape the small

graft which the guides are so rigorously forbidden to practise.

Pompeii is no longer in the keeping of the Italian army; with the

Italian instinct of decentralization the place has claimed the right

of self-government, and now the guides are civilians, and not

soldiers, as they were in my far day. They do not accept fees, but

still they take them. Our guide said that he had a

brother-in-law who had the best restaurant outside the gate, where

we could get luncheon for two francs. As soon as we were in the

hands of the runner for that restaurant the price augmented itself

to two francs and a half; when we mounted to the threshold, lured on

by the fascinating mystery of this increase, it became three francs,

without wine. But as the waiter justly noted, in hovering about us

with the cutlery and napery while he laid the table, a two-fifty

luncheon was unworthy such lords as we. When he began to bring on

the delicious omelette, the admirable fish, the excellent cutlets,

he made us observe that if we paid three francs we ought to eat a

great deal; and there seemed reason in this; at any rate, we did so.

The truth is, that luncheon was worth the money, and more; as for

the Vesuvian wine, it had the rich red blood of the volcano in it,

and it could not be bought in New York for half a franc the bottle,

if at all; at thrice that sum in Naples it was not a third as good. Afterward in the

National Museum at Naples, where most of the precious Pompeian

things, new and old, are heaped up, they still make but a poor show

there beside the treasures of Herculaneum, where the excavation of a

few streets and houses has yielded costlier and lovelier things than

all the lengths and breadths of Pompeii. But not for this would I

turn against Pompeii at the last moment, as it were, though my

second visit had not aesthetically enriched me beyond my first.

I

keep the vision of it under that gray January sky, with Vesuvius

smokeless in the background, and the plan of the dead city, opener

to the eye than ever it could have been in life, inscribed upon the

broadly opened area of the gentle slopes within its gates. Whether

one had not better known it dead than alive, one might not wish

perhaps to say; but the place itself is curiously without pathos;

Newport in ruins might not be touching; possibly all skeletons or

even mummies are without pathos; and Pompeii is a skeleton, or at

the most a mummy, of the past. Seeing what

antiquity so largely was, however, one might be not only resigned

but cheerful in the effacement of any particular piece of it; and

for a help to this at Pompeii I may advise the reader to take with

him a certain little guide-book, written in English by a very

courageous Italian, which I chanced to find in Naples. Though it

treats of the tragical facts with seriousness, it is not with equal

gravity that one reads that sixteen years before the Vesuvian

eruption "the region had been shaken by strong sismic movements,

which induced Pompei inhabitants to forsake precipitately their

habitations. But being the amazement up, they got one's home again

as soon as the earth was quiet and all fear and sadness went off by

memory." Signs of the final disaster to follow were not wanting; the

wells failed, the water-courses were crossed by currents of carbonic

acid; "the domestic animals were also very sensible of the

approaching of the scourge; they lost the habitual vivacity, and

having the food in disgust, had from time to time to complain with

mournful wailings, without justified reasons. . . . The sky became

of a thick darkness, . . . interrupted only by flashes of light

which the lava riverberated, by the bloody gliding of the

thunderbolts, by the incandescence of enormous projectiles, thrown

to an incommensurable highness. . . . Death surprised the charming

town; houses and streets became the tombs of the unhappies hit by an

atrocious torture." The author's

study of the life of Pompeii is notable for diction which, if there

were logic in language, would be admirable English, for while yet in

his mind it must have been "very choice Italian." He tells us that "Pompei's

dwellings are surprising by their specific littleness," and explains

that "Pompei inhabitants, for the habitudes of the climate could

allow, lived almost always to the open sky," just as the Naples

inhabitants do now. "They got home only to rest a little, to fulfill

life wants, to be protected by bad weather. They spent much time

during the day in forum, temples, thermes, tennis-court, or

intervened to public sports, religious functions and meetings. . . .

Few houses only had windows. The sunlight and ventilation to the

ancients was given through empty spaces in the roofs. . . . Hoofs

knocked under the weight of materials thrown out by Vesuvius; it is

undoubted, however, that roofs were provided with covers or

supported terraces. In the middle of the roofs was cut an ouerture

through which air and light brought their benefits to the underlaid

ambients. . . . Proprietor disposed the locals according to his own

delight. . . . So that, there were bed, bath, dining, talking and

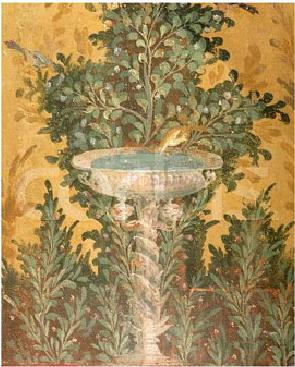

game rooms." In the peristyle "the ground was gardened, the area

shared in flower beds, had narrow paths; herbs, flowers, shrubs were

put with art well in order on flower beds, delighted from time to

time by statues of various subjects," as may be noted in the actual

restorations of some of the Pompeian houses. As for their

spiritual life, "Pompeian's religion, like by Roman people, was the

Paganism. Deities were worshipped in the temples with prayers,

sagrifices, vows, and festivities. . . . Banquets to the Deity were

joined to prayers. In fact, dining tables were dressed near the

altars, and all around them on dining beds, tricli-nari,

placed Divinities statues as these were assembled to own account to

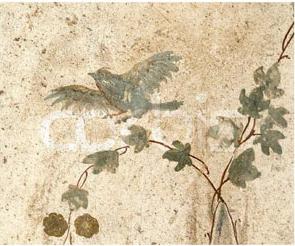

the joyous banquest." Auspices or auguries "gave interpretation to

thunders, lightnings, winds, rain crashes, comets, or to bird songs

and flights. . . . Horuspices inquired the divine will on the animal

bowels, sacrificed to the altar; they took out further indications

by fleshes and bowels flames when burnt on the altar." An important

feature of Pompeian social life was the bath, which "was one of the

hospitality duty, and very often required in several religious

functions. . . . Large and colossal edifices were quite furnished

with all the necessary for care and sport. Besides localities for

all kind of bath--cold, warm, steam bath--didn't want parks, alleys,

and porticos in order to walk; lists rings for gymnastic exercises,

conversation and reading rooms, localities for theatrical

representations, swimming stations, localities for scientific

disquisitions, moral and religious teachings. The most splendid art

works adorned the ambient." When we pass

to the popular amusements we are presented with the materials of

pictures vividly realized in The Last Days of Pompeii [ed.

the opera], but

somewhat faded since. "In the beginning gladiators' rank was made by

condemned to death slaves and war prisoners. Later also thoughtless

young men, who had never learned an advantageous trade, became

gladiators." In the arena they engaged in sham fights till the

spectators demanded blood. Then, "sometimes one provided one's self

nets for wrapping up the adversary, who, hit by a trident much,

frequently die. When the gladiator was deadly wounded, forsaking the

arm, struck down and stretching the index, asked the people grace of

life. The spectators decided up his destiny, turning the thumb to

the breast, or toward the ground. The thumb turned toward the ground

was the unlucky's death doom, and he had without fail the throat cut

off." Such, dimly

but unmistakably seen through our Italian author's well-reasoned

English, were the ancient Pompeians; and, upon the whole, the

visitor to their city could not wish them back in it. I preferred

even those modern Pompeians who followed us so molestively to the

train with bargains in postal-cards and coral. They are very alert,

the modern Pompeians, to catch the note of national character, and I

saw one of them pursuing an elderly American with a spread of

hat-pins, primarily two francs each, and with the appeal, evidently

studied from some fair American girl: "Buy it, Poppa! Six for one

franc. Oh, Poppa, buy it!"

This link

is to an Italian company that makes reproduction Pompeian jewelry,

authorized by Italian museums.

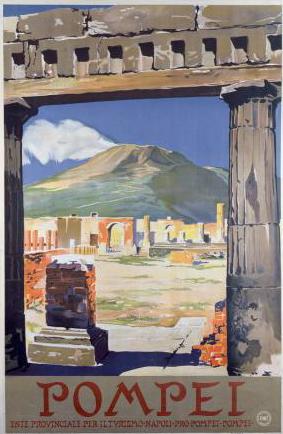

Vesuvius

and Pompeii

![]()

![]()

Roman Fresco from the Oplonti Villa in Pompeii Depicting a Birdbath

![]()

Roman Fresco from the Oplonti Villa in Pompeii Depicting a Flying Bird

![]()

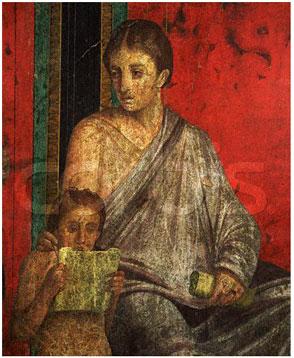

Detail of a Woman from the Fresco Cycle at the Villa of the Mysteries

![]()

Detail of a Woman and a Boy from the Fresco Cycle at the Villa of the Mysteries

Mount Vesuvius, mainland Europe's most active volcano, can be

seen from Naples, Italy, and is a favorite subject of artists,

tourists, and especially naturalists who visit Vesuvius today, but

even more often in the 1800s to observe her then frequent eruptions.

Pompeii and

Vesuvius Circa 1890 - 1900

POMPEII REVISITED

(abridged from Roman Holidays by the

writer William

Dean Howells, 1908, who had previously visited the site in 1865)

Some Amazon.com Books about Pompeii