Candida Martinelli's Italophile Site

Main

Page This family-friendly site celebrates Italian culture for the enjoyment of children and

adults. Site-Overview

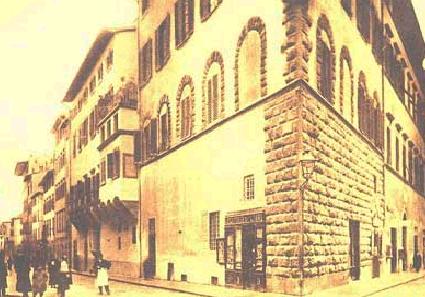

Palazzo Guidi, opposite the Pitti Palace in Florence. It

houses a museum and you can

even rent out the rooms. This is one of a suite of rooms let by Britain's

Landmark Trust which manages Casa Guidi. Click on the image to go

to the Landmark Trust's homepage. Painting of the drawing room in Casa Guidi.

Click on the image to visit the Literary Traveler site's informative

page on Casa Guidi and the Brownings. This is how the drawing room looks today.

Click on the image to read about the efforts it took to create the

museum. Click on the above image to go to The Victorian

Web's wonderfully informative site about Elizabeth Barrett Browning and

her work. Click here

to visit the University of Toronto's site with copies of many of her

poems. The Victorian Web has an equally wonderful site

about Robert Browning and his work. Click on the above image to

visit it. Click here

to visit the University of Toronto's site with copies of many of his

poems. The Pitti Palace and the Boboli Gardens

beyond. These are open to the public now, but were the private

property of the Duke of Florence at the time the Brownings were his

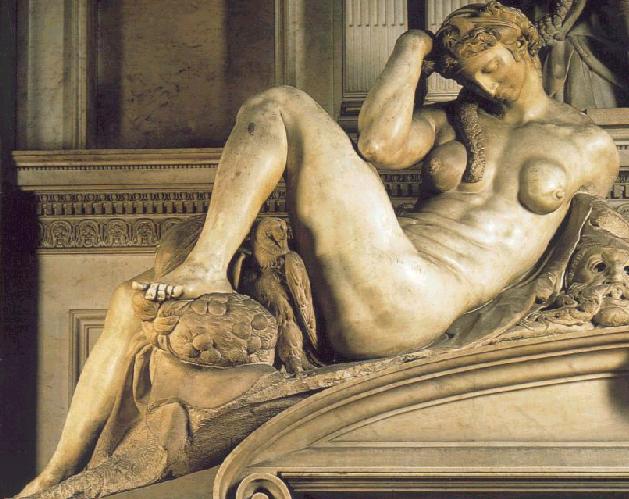

neighbors. They lived at the far right of end of the square. Image of the Cascine from that period. Michelangelo's Night on the Medici Tomb Michelangelo's Day on the Medici Tomb Michelangelo's Twilight on the Medici Tomb Michelangelo's Dawn on the Medici Tomb Michelangelo's Medici Tomb Michelangelo's Giuliano Duke of Nemour This is an image of Elizabeth's tomb in the

Protestant Cemetery in Florence. Click here to go to Eton

College's page describing in detail Casa Guidi's contents. To see what's available as printed books of the Browning's poetry or

biographies of the two, you can use this search tool for Amazon.com. Just

enter 'Books' in the 'Search' field, and 'Browning' (or Elizabeth

Barrett Browning, for example) in the 'Keyword' field. Then click

on the 'Go' button to see what's available, what people's comments about

the books are, and what they cost. Differences

between N. and S. Europe Living

opposite the Pitti Palace Italian

unification and 'Casa Guidi Windows' The poet Robert Browning married the invalid

poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning in 1846 and they lived for most of their

married life together in Florence in an apartment opposite the Pitti

Palace in a building called Palazzo Guidi.

Elizabeth christened their apartment Casa Guidi. Robert’s love affair with Italy was longer

than his wife’s. His

first journey to Italy was in 1838.

and he was inspired by Italy’s history and artists in his

poetry. It was actually Elizabeth’s doctor who

first suggested she be taken to Pisa during the English winter to enjoy

the milder climate. But it

took their elopement to make that happen, because Elizabeth’s

over-protective father did not give his permission for her to travel for

her health, and to avoid his forbidding it, Elizabeth never asked his

permission for her marriage to Robert. Their

love a Florence persisted, and even if they did travel around much of

central and northern Italy, and to England and France, they always

returned to Florence. In

June of 1854 Elizabeth writes: “I

love Florence -- the place looks exquisitely beautiful in its garden

ground of vineyards and olive trees, sung round by the nightingales day

and night…If you take one thing with another, there is no place in the

world like Florence, I am persuaded, for a place to live in -- cheap,

tranquil, cheerful, beautiful, within the limits of civilization yet out

of the crush of it…” All

of Italy fascinated Elizabeth. In

her poem “The North and the South” she explains the differences she

saw between Northern Europe and Southern Europe, namely Italy. The

North and the South (from

May, 1861, written in Rome) ‘Now

give us lands where the olives grow, ‘ Cried

the North to the South, ‘Where

the sun with a golden mouth can blow Blue

bubbles of grapes down a vineyard-row!’ Cried

the North to the South. ‘Now

give us men from the sunless plain,’ Cried

the South to the North, ‘By

need of work in the snow and the rain, Made

strong, and brave by familiar pain!’ Cried

the South to the North. ‘Give

lucider hills and intenser seas,’ Said

the North to the South, ‘Since

ever by symbols and bright degrees Art,

childlike, climbs to the dear Lord’s knees,’ Said

the North to the South. ‘Give

strenuous souls for belief and prayer,’ Said

the South to the North, ‘That

stand in the dark on the lowest stair, While

affirming of God, “He is certainly there,”’ Said

the South to the North. “Yet

oh, for the skies that are softer and higher!’ Sighed

the North to the South; ‘For

the flowers that blaze, and the trees that aspire, And

the insects made of a song or a fire!’ Sighed

the North to the South. ‘And

oh, for a seer to discern the same!’ Sighed

the South to the North! ‘For

a poet’s tongue of baptismal flame, To

call the tree or the flower by its name!’ Sighed

the South to the North. The

North sent therefore a man of men, As

a grace to the South’ And

thus to Rome came Andersen. -

‘Alas, but must you take him again?’ Said

the South to the North. Notes:

It’s supposed that Elizabeth was referring to Hans Christian

Andersen who visited Naples and Rome and was the toast of the town for

his fanciful tales. The

reference to men who can name the plants is probably to Linnaeus, a

Scandinavian, who assigned Latin names to plants, names that are used to this

day. It is in December 1847 that the first

letters arrive from furnished rooms near the Pitti Palace. Elizabeth writes: “So

here we are in the Pitti till April, in small rooms yellow with sunshine

from morning till evening, and

most days I am able to get out into the piazza and walk up and down

for twenty minutes without feeling a breath of the actual

winter…” In

May 1848 this comes in a letter from Palazzo Guidi: “In fact we have really done it magnificently, and planted

ourselves in the Guidi Palace in the favourite suite of the last Count

(his arms are in scagliola on the floor of my bedroom). Though we have six beautiful rooms and a kitchen, three of

them quite palace rooms and opening on a terrace, and though such

furniture as comes by slow degrees into them is antique and worthy of

the place, we yet shall

have saved money by the end of this year…a stone's throw, too,

it is from the Pitti, and really in my present mind

I would hardly exchange with the Grand Duke himself.

By the bye, as to street, we have no spectators in windows in

just the grey wall of a church called San Felice for good omen.” In a letter from July 1848 she writes of how

they enjoy walking from their apartment near the Pitti Palace, over the Ponte

Vecchio to the main square, La Piazza delle Signorie, to sit

in the Loggia dei Lanzi: “Robert

and I go out often after tea in a wandering walk to sit in the Loggia

and look at the Perseus, or, better still, at the divine sunsets on the

Arno, turning it to pure gold under the bridges.”

Elizabeth

describes in April of 1850 their wandering in the Florentine public

gardens that follow the Arno river, the Cascine. “We drive day by day through the lovely Cascine,

just sweeping through the city. Just

such a window where Bianca Capello looked out to see the Duke go by --

and just such a door where Tasso stood and where Dante drew his chair

out to sit. Strange to have

all that old world life about us, and the blue sky so bright…” Elizabeth

wrote a poem set in the Cascine called “The Dance”.

It is about the Florentines expressing their gratitude to French

soldiers who offered a reprieve from the repressive control of the

Austrians. The

Dance You

remember down at Florence our Cascine, Where

the people on the feast-days walk and drive, And,

through the trees, long-drawn in many a green way, O’er-roofing

hum and murmur like a hive, The

river and the mountains look alive? You

remember the piazzone there, the stand-place Of

carriages a-brim with Florence Beauties, Who

lean and melt to music as the band plays, Or

smile and chat with some one who afoot is, Or

on horseback, in observance of male duties? ‘Tis

so pretty, in the afternoons of summer, So

many gracious faces brought together! Call

it rout, or call it concert, they have come here, In

the floating of the fan and of the feather, To

reciprocate with beauty the fine weather. While

the flower-girls offer nosegays (because they too Go

with other sweets) at every carriage-door; Here,

by shake of a white finger, signed away to Some

next buyer, who sits buying score on score, Piling

roses upon roses evermore. And

last season, when the French camp had its station In

the meadow-ground, things quickened and grew gayer Through

the mingling of the liberating nation With

this people; groups of Frenchmen everywhere, Strolling,

gazing, judging lightly…’who was fair.’ Then

the noblest lady present took upon her To

speak nobly from her carriage for the rest; ‘Pray

these officers from France to do us honour By

dancing with us straightway.” - The request Was

gravely apprehended as addressed. And

the men of France bareheaded, bowing lowly, Led

out each a proud signora to the space Which

the startled crowd had rounded for them - slowly, Just

a touch of still emotion in his face, Not

presuming, through the symbol, on the grace. There

was silence in the people: some lips trembled, But

none jested. Broke the

music, at a glance: And

the daughters of our princes, thus assembled, Stepped

the measure with the gallant sons of France. Hush!

It might have been a Mass, and not a dance. And

they danced there till the blue that overskied us Swooned

with passion, though the footing seemed sedate; And

the mountains, heaving mighty hearts beside us, Sighed

a rapture in a shadow, to dilate, And

touch the holy stone where Date sate. Then

the sons of France bareheaded, lowly bowing, Led

the ladies back where kinsmen of the south Stood,

received then; - till, with burst of overflowing Feeling…husbands,

brothers, Florence’s male youth, Turned,

and kissed the martial strangers mouth to mouth. And

a cry went up, a cry from all that people! -

You have heard a people cheering, you suppose, For

the Member, Mayor...with chorus from the steeple? This

was different: scarce as loud perhaps (who knows?), For

we saw wet eyes around us ere the close. And

we felt as if a nation, too long borne in By

hard wrongers, comprehending in such attitude That

God had spoken somewhere since the morning, That

men were somehow brothers, by no platitude, Cried

exultant in great wonder and free gratitude. Their son, Robert Weidemann Barrett

Browning, was born on March 9, 1849 in their bedroom in Casa Guidi.

He later bought Palazzo Guidi and stored all his parent’s

possessions there and had hoped to create a shrine to them, but events

overtook him, and the museum was not created until 1995. Their son shared his parent’s love of

Italy and even lived with his wife in Venice’s famous palace on the

Grand Canal, Ca’ Rezzonico, for a while, before making his permanent

home in Asolo. His mother

called him Pen, but in her poem “A Tale of Villafranca” she calls

him “my Florentine”, and comments on his eyes:

“They say your eyes, my Florentine, are English: it may be: and

yet I’ve marked as blue a pair following the doves across the square

at Venice by the sea.” Her 1851 poem “Casa Guidi Windows”

describes in two parts Italy’s growing Risorgimento, or unification

movement, and it’s intensifying struggle for nationhood against the

foreign powers who administered her fate and kept her looking like a

jigsaw puzzle on the maps. The

poem made her an instant hero in Italy, but it was poorly received

abroad, where commentators felt female poets should stick to love

sonnets and eschew politics. Only

later, and mainly by female writers, was the poem’s beauty and passion

appreciated. In the poem, Elizabeth makes many references

to Florence, and to Italy’s illustrious cultural and historical icons.

But it is often the first paragraph that catches people’s eye,

ear and heart. The great

political issue is introduced by a recounting of something she’s heard

through the windows of Casa Guidi.

Later she recounts what she’s seen through the same windows,

hence the title of the poem. Here

are a few excepts from the first half of the poem. Excerpts from Casa Guidi Windows (from

1851) The first stanzas are the most famous of the

poem. I

heard last night a little child go singing ‘Neath

Casa Guidi windows, by the church, O

bella libertà, O

bella! Stringing The

same words still on notes he went in search So

high for, you concluded the upspringing Of

such a nimble bird to sky from perch Must

leave the whole bush in a tremble green, And

that the heart of Italy must beat, While

such a voice had leave to rise serene ‘Twixt

church and palace of a Florence street! A

little child, too, who not long had been By

mothers’s finger steadied on his feet, And

still O bella libertà he sang. Very soon after she praises

Florence’s beauty. For

me who stand in Italy to-day, Where

worthier poets stood and sang before, I

kiss their footsteps, yet their words gainsay. I

can but muse in hope upon this shore Of

golden Arno as it shoots away Through

Florence’ heart beneath her bridges four! Bent

bridges, seeming to strain off like bows, And

tremble while the arrowy undertide Shoots

on and cleaves the marble as it goes, And

strikes up palace-walls on either side, And

froths the cornice out in glittering rows, With

doors and windows quaintly multiplied, And

terrace-sweeps, and gazers upon all, By

whom if flower or kerchief were thrown out From

any lattice there, the same would fall Into

the river underneath no doubt, It

runs so close and fast ’twixt wall and wall. How

beautiful! Then right after, she writes of

Michelangelo’s sculptures Dawn, Twilight, Night and Day in the Medici

Tomb in the Church of St. Lawrence, and how they must suffer to see

Italians un-free. Michel’s

Night and Day And

Dawn and Twilight wait in marble scorn, Like

dogs upon a dunghill, couched on clay From

whence the Medicean stamp’s outworn, The

final putting off of all such sway By

all such hands, and freeing of the unborn In

Florence and the great world outside Florence. Three

hundred years his patient statues wait In

that small chapel for the dim St Lawrence. Day’s

eyes are breaking bold and passionate Over

his shoulder, and will flash abhorrence On

darkness and with level looks meet fate, When

once loose from that marble film of theirs; The

Night has wild dreams in her sleep, the Dawn Is

haggard as the sleepless, Twilight wears A

sort of horror; as the veil withdrawn ‘Twixt

the artist’s soul and works had left them heirs Of

speechless thoughts which would not quail nor fawn, Of

angers and contempts, of hope and love; For

not without a meaning did he place The

princely Urbino on the seat above With

everlasting shadow on his face, While

the slow dawns and twilights disapprove The

ashes of his long-extinguished race, Which

never more shall clog the feet of men. She later suggests Italy

deserves to be a nation because of it’s rich cultural heritage. ‘Now

tell us what is Italy?’ men ask: And

others answer, ‘Virgil, Cicero, Catullus,

Caesar.’ What beside? To task The

memory closer - ‘Why, Boccaccio, Dante,

Petrarca,’ - and if still the flask Appears

to yield its wine by drops too slow, - ‘Angelo,

Raffael, Pergolese,’ - all Whose

strong hearts beat through stone, or charged again The

paints with fire of souls electrical, Or

broke up heaven for music. She digresses for another ode to

Florence’s beauty. Shall

I say What

made my heart beat with exulting love, A

few weeks back? - …The

day was such a day As

Florence owes the sun. The sky above, Its

weight upon the mountains seemed to lay, And

palpitate in glory, like a dove Who

has flown too fast, full-hearted! - take away The

image! For the heart of man beat higher That

day in Florence, flooding all her streets And

piazzas with a tumult and desire. She

follows with passages to give encouragement to Italians in the struggle

for nationhood, but ends with a plea to the true intended audience of

her poem, Italophiles among the English and other world powers. Therefore

let us all Refreshed

in England or in other land, By

visions, with their fountain-rise and fall, Of

this earth’s darling, - we, who understand A

little how the Tuscan musical Vowels

do round themselves as if they planned Eternities

of separate sweetness, - we, Who

loved Sorrento vines in picture-book, Or

ere in wine-cup we pledged faith or glee, - Who

loved Rome’s wolf, with demi-gods at suck, Or

ere we loved truth’s own divinity, - Who

loved, in brief, the classic hill and brook, And

Ovid’s dreaming tales, and Petrarch’s song, Or

ere we loved Love’s self even! - let us give The

blessing of our souls, (and wish them strong To

bear it to the height where prayers arrive, When

faithful spirits pray against a wrong,) To

this great cause of southern men, who strive In

God’s name for man’s rights, and shall not fail! Elizabeth’s poor health, sometimes

explained by spinal damage, sometimes lung damage, sometimes

Tuberculosis, and sometimes by the prescribed medications she used,

worsened when she learned of Cavour’s death.

Cavour was the diplomat to Garibaldi’s soldier, and together

they paved the way for Italian unification.

Elizabeth passed away in Florence, and while Robert left,

heartbroken, with their son for England, never to return to Florence

again, he did not lose his love of Italy. Robert wrote after his wife’s

death, when he was settled in England, “…How I yearn, yearn for Italy at the close of my

life!…” He was in the

process of purchasing land in Venice when he passed away.

He died in Venice’s famous Ca’ Rezzonico, a palace on the

grand canal, the home of his son and daughter-in-law.

A plaque was placed on the building that reads: “A Roberto Browning, morto in questo palazzo, il 12 dicembre

1889, Venezia, pose.” (To Robert Browning, who died in this building,

December 12, 1889, Venice, may he rest in peace.”

Two lines from one of his poems follows it:

“Open my heart and you will see, Graved inside of it,

`Italy'.” Rezzonico Palace, Ca' Rezzonico,

Venice

Elizabeth lies interred in the old

Protestant Cemetery in Florence with the inscription expressing

Italy’s gratitude to her support for nationhood engraved on her tomb.

Two of her books of poetry dealt directly with the cause of

national unity: Casa Guidi

Windows from 1851, and Poems Before Congress from 1861, and they served

to build support around the world for Italian Unification.

It was later the same year as her death, 1861, that the Kingdom

of Italy was declared.

My References:

Quotes from letters are taken from:

The

Poets Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning - Italophiles in Florence

![]()

The Brownings and Italy

Differences Between North and South Europe

Living Opposite

the Pitti Palace

The

Cascine and 'The Dance'

Their Son, Another Italophile

Italian

Unification and 'Casa Guidi Windows'

Their Deaths in Italy