Candida Martinelli's Italophile Site

Main

Page This family-friendly site celebrates Italian culture for the enjoyment of children and

adults. Site-Overview

Excerpts Below: 1 -

How the Chinese burn black stones (coal) 2 -

The Maji, three Kings, a fable heard along the way 3 -

Kublai Khan and his four wives 4 -

How the dead Khans are buried 5 -

Giant, reclining Buddas 6 -

Xanadu's pleasure dome 7 -

The Khan's palace compound in Beijing 8 -

Ancient Beijing during the Yuan (Mongol) Dynasty 9 -

Nomadic Tartars (Mongols) 10

- Feasting with the Khan 11

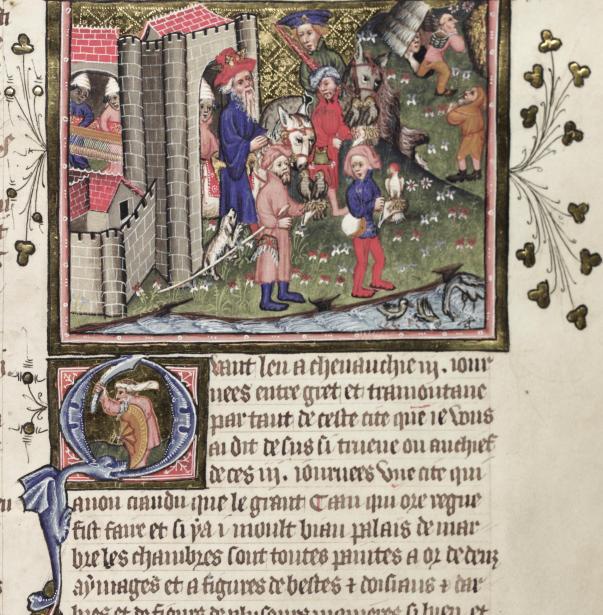

- The Khan goes falconing 12

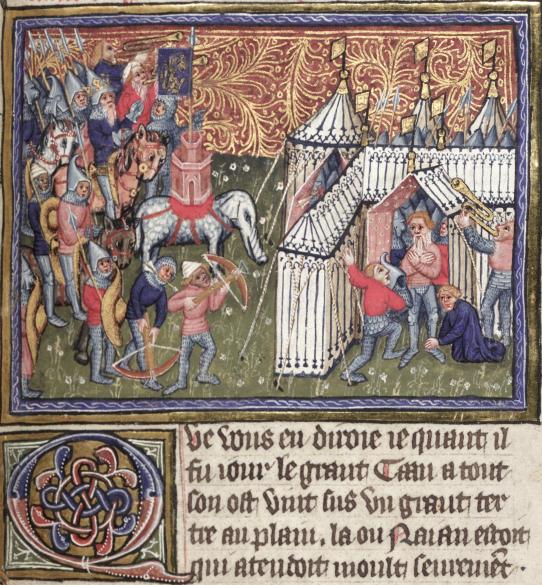

- The tent-city erected for the hunting party Sections Below:

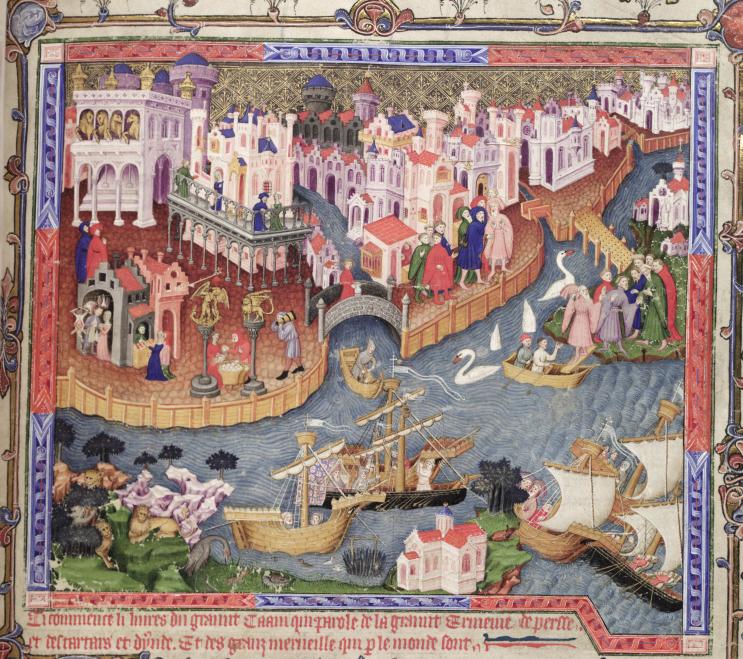

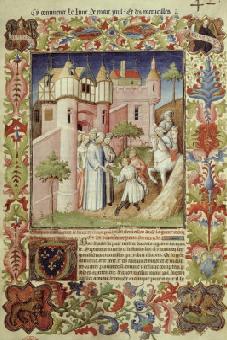

Illumination Illustrations

from 1400 Book (unique and very beautiful!) Marco describes how in China people burned coal (black stones) to

warm their homes and heat their water. This is in contrast to

Venice and other places where coal was not found locally, and where they

burned wood, which is scarce and cumbersome. You'll note that

taking a bath 3 times a week was seen as odd. Medieval Europe was

a smelly place, and not just from the dirty people, but from the

pervasive smell of burning wood. "It is a

fact that all over the country of Cathay there is a kind of black stones

existing in beds in the mountains, which they dig out and burn like

firewood. If you supply the fire with them at night, and see that they

are well kindled, you will find them still alight in the morning; and

they make such capital fuel that no other is used throughout the

country. It is true that they have plenty of wood also, but they do not

burn it, because those stones burn better and cost less.

"Moreover with that vast number of people, and the number of hot baths

that they maintain--for every one has such a bath at least three times a

week, and in winter if possible every day, whilst every nobleman and man

of wealth has a private bath for his own use--the wood would not suffice

for the purpose. This is an excerpt from Marco's book about the Three Kings or the

Magi who visited Jesus of Nazareth just after Jesus's birth. There are many tales about the

Magi,

in Jewish writings, Muslim writings, and Christian writings. And

while none agree completely, they

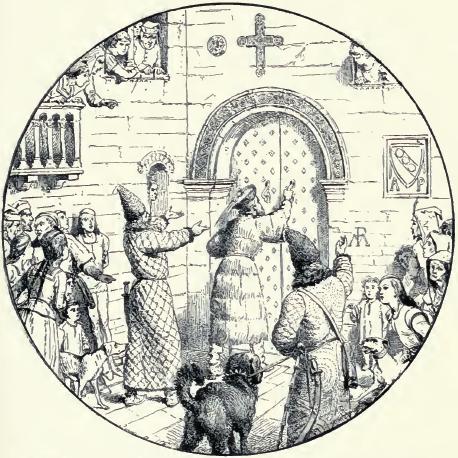

are all, however, very entertaining. "Persia is a great

country, which was in old times very illustrious and powerful; but now

the Tartars have wasted and destroyed it. In Persia is the city of SABA,

from which the Three Magi set out when they went to worship Jesus

Christ; and in this city they are buried, in three very large and

beautiful monuments, side by side. And above them there is a square

building, carefully kept. 'The bodies are

still entire, with the hair and beard remaining. One of these was called

Jaspar, the second Melchior, and the third Balthasar. Messer Marco Polo

asked a great many questions of the people of that city as to those

Three Magi, but never one could he find that knew aught of the matter,

except that these were three kings who were buried there in days of old.

'However, at a

place three days' journey distant he heard of what I am going to tell

you. He found a village there which goes by the name of CALA ATAPERISTAN,

which is as much as to say, "The Castle of the Fire-worshippers." And

the name is rightly applied, for the people there do worship fire, and I

will tell you why.

'They relate that

in old times three kings of that country went away to worship a Prophet

that was born, and they carried with them three manner of offerings,

Gold, and Frankincense, and Myrrh; in order to ascertain whether that

Prophet were God, or an earthly King, or a Physician. For, said they, if

he take the Gold, then he is an earthly King; if he take the Incense he

is God; if he take the Myrrh he is a Physician. 'So it came to pass

when they had come to the place where the Child was born, the youngest

of the Three Kings went in first, and found the Child apparently just of

his own age; so he went forth again marvelling greatly. 'The middle one

entered next, and like the first he found the Child seemingly of his own

age; so he also went forth again and marvelled greatly. 'Lastly, the eldest

went in, and as it had befallen the other two, so it befell him. And he

went forth very pensive. 'And when the three

had rejoined one another, each told what he had seen; and then they all

marvelled the more. So they agreed to go in all three together, and on

doing so they beheld the Child with the appearance of its actual age, to

wit, some thirteen days. 'Then they adored,

and presented their Gold and Incense and Myrrh. And the Child took all

the three offerings, and then gave them a small closed box; whereupon

the Kings departed to return into their own land. And when they had

ridden many days they said they would see what the Child had given them.

So they opened the little box, and inside it they found a stone. On

seeing this they began to wonder what this might be that the Child had

given them, and what was the import thereof. 'Now the

signification was this: when they presented their offerings, the Child

had accepted all three, and when they saw that they had said within

themselves that He was the True God, and the True King, and the True

Physician. And what the gift of the stone implied was that this Faith

which had begun in them should abide firm as a rock. For He well knew

what was in their thoughts. 'Howbeit, they had

no understanding at all of this signification of the gift of the stone;

so they cast it into a well. Then straightway a fire from Heaven

descended into that well wherein the stone had been cast. And when the

Three Kings beheld this marvel they were sore amazed, and it greatly

repented them that they had cast away the stone; for well they then

perceived that it had a great and holy meaning.

'So they took of

that fire, and carried it into their own country, and placed it in a

rich and beautiful church. And there the people keep it continually

burning, and worship it as a god, and all the sacrifices they offer are

kindled with that fire. 'And if ever the

fire becomes extinct they go to other cities round about where the same

faith is held, and obtain of that fire from them, and carry it to the

church. And this is the reason why the people of this country worship

fire. They will often go ten days' journey to get of that fire.

'Such then was the

story told by the people of that Castle to Messer Marco Polo; they

declared to him for a truth that such was their history, and that one of

the three kings was of the city called SABA, and the second of AVA, and

the third of that very Castle where they still worship fire, with

the people of all the country round about." Marco Polo captured the imaginations of Europeans with his stories of

adventure in foreign lands. His books inspired other writers to

imagine what a young Marco Polo might have been like, and to use his

made-up story to inspired young readers to greatness.

Here Marco described Kublai Khan and his four wives. "The personal appearance of the Great Kaan, Lord of Lords, whose name

is Cublay, is such as I shall now tell you. He is of a good stature,

neither tall nor short, but of a middle height. He has a becoming amount

of flesh, and is very shapely in all his limbs. His complexion is white

and red, the eyes black and fine, the nose well formed and well set on. 'He has four wives, whom he retains permanently as his legitimate

consorts; and the eldest of his sons by those four wives ought by rights

to be emperor;--I mean when his father dies. Those four ladies are

called empresses, but each is distinguished also by her proper name. 'And each of them has a special court of her own, very grand and

ample; no one of them having fewer than 300 fair and charming damsels.

They have also many pages and eunuchs, and a number of other attendants

of both sexes; so that each of these ladies has not less than 10,000

persons attached to her court." Marco Polo became a household name, and represented the mysterious

and foreign far east. Products such as tea were named for him over

the years.

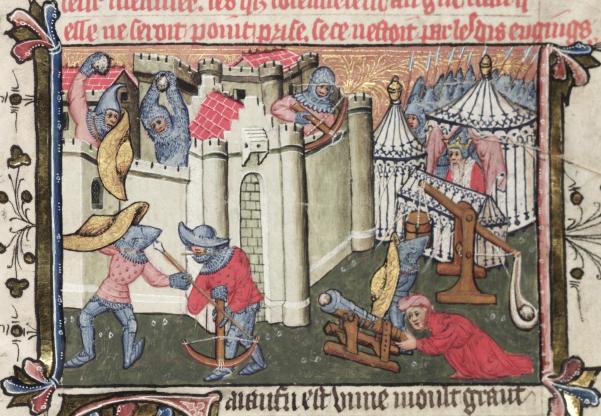

This is an excerpt from Marco Polo's book, telling how the Khans were

brought to their chosen place of burial. "To Chingis-khan succeeded Cyhn-khan; the third was Bathyn-khan, the

fourth Esu-khan, the fifth Mongu-khan, the sixth Kublai-khan, who became

greater and more powerful than all the others, inasmuch as he inherited

what his predecessors possessed, and afterwards, during a reign of

nearly sixty years, acquired, it may be said, the remainder of the

world. 'The title of khan, or kaan, is equivalent to emperor in our

language. 'It has been an invariable custom that all the grand khans and chiefs

of the race of Chingis-khan should be carried for interment to a certain

lofty mountain named Altai, and in whatever place they may happen to

die, even if it should be at the distance of a hundred days' journey,

they are nevertheless conveyed there." [ed. The Altai Mountains are a mountain range in central Asia, where

Russia, China, Mongolia and Kazakhstan come together. Here are two

images.] "It is likewise the custom, during the progress of removing the

bodies of these princes, for those who form the escort to sacrifice such

persons as they chance to meet on the road, saying to them, "Depart for

the next world, and there attend upon your deceased master," believing

that all they kill do actually become his servants in the next life. 'They do the same also with respect to horses, killing the best of

the stud, in order that he may have the use of them. 'When the corpse of Mongu was transported to this mountain, the

horsemen who accompanied it, having this blind and horrible persuasion,

slew upwards of twenty thousand persons who fell in their way." Marco Polo is not forgotten in Asia, as these images show. He

helped show the east not as aggressive hoards, but as civilized nations

with great resources at their disposal. He also showed that trade

contacts could lead to mutual understanding, dialog and security.

Marco describes giant, reclining Buddas in one town. These were

common along the Silk Route. In the news in the last years have

been the giant, standing Buddas of Afghanistan. But archeologists

have found the remains of giant, reclining Buddas at the same site. "Campichu is also a city of Tangut, and a very great and noble one.

Indeed it is the capital and place of government of the whole province

of Tangut. [NOTE 1] 'The people are Idolaters [ed. Buddists], Saracens [ed. Arabs-Moslims],

and Christians, and the latter have three very fine churches in the

city, whilst the Idolaters have many minsters and abbeys after their

fashion. 'In these they have an enormous number of idols, both small and

great, certain of the latter being a good ten paces in stature; some of

them being of wood, others of clay, and others yet of stone. 'They are all highly polished, and then covered with gold. The great

idols of which I speak lie at length. And round about them there are

other figures of considerable size, as if adoring and paying homage

before them." Over the years that followed the publication of Marco Polo's book,

explorers sailed out across the seas and discovered that Marco Polo was

not making things up in his book. The places he mentioned really

existed, sometimes altered from his description, but they really

existed. They were included in maps of the world, some used by

Columbus on his travels. This excerpt about the Khan's summer palace was the inspiration for the poet Coleridge's famous poem

'Xanadu' that began: "In Xanadu did Kubla Khan A stately

pleasure-dome decree...". "And when you have ridden three days from the city last mentioned,

between north-east and north, you come to a city called CHANDU,which was

built by the Kaan [ed. Khan] now reigning. 'There is at this place a very fine marble Palace, the rooms of which

are all gilt and painted with figures of men and beasts and birds, and

with a variety of trees and flowers, all executed with such exquisite

art that you regard them with delight and astonishment. 'Round this Palace a wall is built, inclosing a compass of 16 miles,

and inside the Park there are fountains and rivers and brooks, and

beautiful meadows, with all kinds of wild animals (excluding such as are

of ferocious nature), which the Emperor has procured and placed there to

supply food for his gerfalcons and hawks, which he keeps there in mew.

Of these there are more than 200 gerfalcons alone, without reckoning the

other hawks. 'The Kaan himself goes every week to see his birds sitting in mew,

and sometimes he rides through the park with a leopard behind him on his

horse's croup; and then if he sees any animal that takes his fancy, he

slips his leopard at it,and the game when taken is made over to feed the

hawks in mew. This he does for diversion." Here is a lovely site set up by a university, that matches comments

in Marco Polo's text with actual locations on a map. Go to the

site, and use the clickable map. A

university site offers an interactive map with locations mentioned

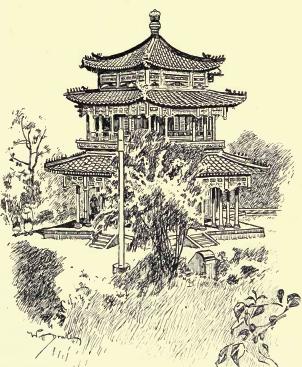

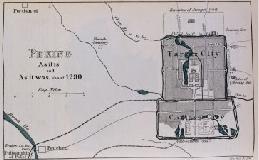

by Marco Polo, and what he said about the location. Here are some of Marco's descriptions of the Khan's palace compound

in Cambaluc, or Peking, or Beijing. Today, it is called the

Forbidden City, enclosed in the Imperial City, but what exist today was

built several centuries later. When the Mongol rulers, the

Yuan dynasty, were overthrown, their city was raised to the ground, only

to be built over by a later dynasty. "You must know that for three months of the year, to wit December,

January, and February, the Great Kaan resides in the capital city of

Cathay, which is called CAMBALUC, and which is at the north-eastern

extremity of the country. In that city stands his great Palace, and now

I will tell you what it is like. 'It is enclosed all round by a great wall forming a square, each side

of which is a mile in length; that is to say, the whole compass thereof

is four miles. This you may depend on; it is also very thick, and a good

ten paces in height, whitewashed and loop-holed all round. 'At each angle of the wall there is a very fine and rich palace in

which the war-harness of the Emperor is kept, such as bows and quivers,

saddles and bridles, and bowstrings, and everything needful for an army. 'Also midway between every two of these Corner Palaces there is

another of the like; so that taking the whole compass of the enclosure

you find eight vast Palaces stored with the Great Lord's harness of war. 'And you must understand that each Palace is assigned to only one

kind of article; thus one is stored with bows, a second with saddles, a

third with bridles, and so on in succession right round.

[ed. Mongol Battle outfit from this period] 'The great wall has five gates on its southern face, the middle one

being the great gate which is never opened on any occasion except when

the Great Kaan himself goes forth or enters. Close on either side of

this great gate is a smaller one by which all other people pass; and

then towards each angle is another great gate, also open to people in

general; so that on that side there are five gates in all. 'Inside of this wall there is a second, enclosing a space that is

somewhat greater in length than in breadth. This enclosure also has

eight palaces corresponding to those of the outer wall, and stored like

them with the Lord's harness of war. This wall also hath five gates on

the southern face, corresponding to those in the outer wall, and hath

one gate on each of the other faces, as the outer wall hath also. 'In the middle of the second enclosure is the Lord's Great Palace,

and I will tell you what it is like. You must know that it is the

greatest Palace that ever was. Towards the north it is in contact with

the outer wall, whilst towards the south there is a vacant space which

the Barons and the soldiers are constantly traversing. [ed. This is the last Khan's palace in Mongolia, still built to a

similar design as that described by Marco Polo.] 'The Palace itself hath no upper story, but is all on the ground

floor, only the basement is raised some ten palms above the surrounding

soil and this elevation is retained by a wall of marble raised to the

level of the pavement, two paces in width and projecting beyond the base

of the Palace so as to form a kind of terrace-walk, by which people can

pass round the building, and which is exposed to view, whilst on the

outer edge of the wall there is a very fine pillared balustrade; and up

to this the people are allowed to come. 'The roof is very lofty, and the walls of the Palace are all covered

with gold and silver. They are also adorned with representations of

dragons, sculptured and gilt, beasts and birds, knights and idols, and

sundry other subjects. And on the ceiling too you see nothing but gold

and silver and painting. 'On each of the four sides there is a great marble staircase leading

to the top of the marble wall, and forming the approach to the Palace. 'The Hall of the Palace is so large that it could easily dine 6000

people; and it is quite a marvel to see how many rooms there are

besides. The building is altogether so vast, so rich, and so beautiful,

that no man on earth could design anything superior to it. 'The outside of the roof also is all coloured with vermilion and

yellow and green and blue and other hues, which are fixed with a varnish

so fine and exquisite that they shine like crystal, and lend a

resplendent lustre to the Palace as seen for a great way round. This

roof is made too with such strength and solidity that it is fit to last

for ever. 'On the interior side of the Palace are large buildings with halls

and chambers, where the Emperor's private property is placed, such as

his treasures of gold, silver, gems, pearls, and gold plate, and in

which reside the ladies and concubines. There he occupies himself at his

own convenience, and no one else has access. 'Between the two walls of the enclosure which I have described, there

are fine parks and beautiful trees bearing a variety of fruits. There

are beasts also of sundry kinds, such as white stags and fallow deer,

gazelles and roebucks, and fine squirrels of various sorts, with numbers

also of the animal that gives the musk, and all manner of other

beautiful creatures, insomuch that the whole place is full of them, and

no spot remains void except where there is traffic of people going and

coming. 'The parks are covered with abundant grass; and the roads through

them being all paved and raised two cubits above the surface, they never

become muddy, nor does the rain lodge on them, but flows off into the

meadows, quickening the soil and producing that abundance of herbage. 'From that corner of the enclosure which is towards the north-west

there extends a fine Lake, containing foison of fish of different kinds

which the Emperor hath caused to be put in there, so that whenever he

desires any he can have them at his pleasure. A river enters this lake

and issues from it, but there is a grating of iron or brass put up so

that the fish cannot escape in that way. 'Moreover on the north side of the Palace, about a bow-shot off,

there is a hill which has been made by art from the earth dug out of the

lake; it is a good hundred paces in height and a mile in compass. This

hill is entirely covered with trees that never lose their leaves, but

remain ever green. The Khan's Palace Compound 'And I assure you that wherever a beautiful tree may exist, and the

Emperor gets news of it, he sends for it and has it transported bodily

with all its roots and the earth attached to them, and planted on that

hill of his. No matter how big the tree may be, he gets it carried by

his elephants; and in this way he has got together the most beautiful

collection of trees in all the world. 'And he has also caused the whole hill to be covered with the ore of

azure, which is very green. And thus not only are the trees all green,

but the hill itself is all green likewise; and there is nothing to be

seen on it that is not green; and hence it is called the GREEN MOUNT;

and in good sooth 'tis named well. 'On the top of the hill again there is a fine big palace which is all

green inside and out; and thus the hill, and the trees, and the palace

form together a charming spectacle; and it is marvellous to see their

uniformity of colour! Everybody who sees them is delighted. And the

Great Kaan had caused this beautiful prospect to be formed for the

comfort and solace and delectation of his heart. 'You must know that beside the Palace (that we have been describing),

i.e. the Great Palace, the Emperor has caused another to be built just

like his own in every respect, and this he hath done for his son when he

shall reign and be Emperor after him. 'Hence it is made just in the same fashion and of the same size, so

that everything can be carried on in the same manner after his own

death. It stands on the other side of the lake from the Great Kaan's

Palace, and there is a bridge crossing the water from one to the other.

The Prince in question holds now a Seal of Empire, but not with such

complete authority as the Great Kaan, who remains supreme as long as he

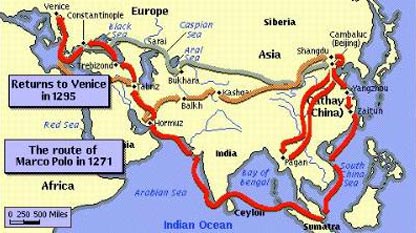

lives. Here's another map for which I can't find the original location on

the web. It shows Marco Polo's travels from Venice to China (the

yellow line) and Marco father

and uncle's path to China, which are also described by Marco in his book), while

in China (the red lines that go south then north from Beijing), and on his way home to Venice

(the red lines). This is how Marco Polo describes ancient Beijing under the Yuan

Dynasty, the Mongol Dynasty. "Now there was on that spot in old times a great and noble city

called CAMBALUC, which is as much as to say in our tongue "The city of

the Emperor." 'But the Great Kaan was informed by his Astrologers that this city

would prove rebellious, and raise great disorders against his imperial

authority. So he caused the present city to be built close beside the

old one, with only a river between them. And he caused the people of the

old city to be removed to the new town that he had founded; and this is

called TAIDU. 'However, he allowed a portion of the people which he did not suspect

to remain in the old city, because the new one could not hold the whole

of them, big as it is. 'As regards the size of this (new) city you must know that it has a

compass of 24 miles, for each side of it hath a length of 6 miles, and

it is four-square. And it is all walled round with walls of earth which

have a thickness of full ten paces at bottom, and a height of more than

10 paces; but they are not so thick at top, for they diminish in

thickness as they rise, so that at top they are only about 3 paces

thick. And they are provided throughout with loop-holed battlements,

which are all whitewashed. 'There are 12 gates, and over each gate there is a great and handsome

palace, so that there are on each side of the square three gates and

five palaces; for (I ought to mention) there is at each angle also a

great and handsome palace. In those palaces are vast halls in which are

kept the arms of the city garrison. The West Gate of Beijing 'The streets are so straight and wide that you can see right along

them from end to end and from one gate to the other. And up and down the

city there are beautiful palaces, and many great and fine hostelries,

and fine houses in great numbers. 'All the plots of ground on which the houses of the city are built

are four-square, and laid out with straight lines; all the plots being

occupied by great and spacious palaces, with courts and gardens of

proportionate size. All these plots were assigned to different heads of

families. 'Each square plot is encompassed by handsome streets for traffic; and

thus the whole city is arranged in squares just like a chess-board, and

disposed in a manner so perfect and masterly that it is impossible to

give a description that should do it justice. 'Moreover, in the middle of the city there is a great clock--that is

to say, a bell--which is struck at night. And after it has struck three

times no one must go out in the city, unless it be for the needs of a

woman in labour, or of the sick. And those who go about on such errands

are bound to carry lanterns with them. 'Moreover, the established guard at each gate of the city is 1000

armed men; not that you are to imagine this guard is kept up for fear of

any attack, but only as a guard of honour for the Sovereign, who resides

there, and to prevent thieves from doing mischief in the town." This image from Wikipedia shows the Mongol empire over time, the same

time the Polos were traveling to and from the empire.

After it's growth, the empire was eventually

divided up. To see more detail, visit the

Wikipedia page for this image.

Here is another excerpt from Marco Polo's book, about the Tartars

(Mongolians). "The Tartars never remain fixed, but as the winter approaches remove

to the plains of a warmer region, to find sufficient pasture for their

cattle; and in summer they frequent cold areas in the mountains, where

there is water and verdure, and their cattle are free from the annoyance

of horse-flies and other biting insects. "During two or three months they go progressively higher and seek

fresh pasture, the grass not being adequate in any one place to feed the

multitudes of which their herds and flocks consist. "Their huts or tents are formed of rods covered with felt, exactly

round, and nicely put together, so they can gather them into one bundle,

and make them up as packages, which they carry along with them in their

migrations upon a sort of car with four wheels. "When they have occasion to set them up again, they always make the

entrance front to the south. [ed. gehr or a yurt] "Besides these cars they have a superior kind of vehicle upon two

wheels, also covered with black felt so well that they protect those

within it from wet during a whole day of rain. These are drawn by oxen

and camels, and convey their wives and children, their utensils, and

whatever provisions they require. "The women attend to their trading concerns, buy and sell, and

provide everything necessary for their husbands and their families; the

time of the men is devoted entirely to hunting, hawking, and matters

that relate to the military life. They have the best falcons in the

world, and also the best dogs. "They live entirely upon flesh and milk, eating the produce of their

sport, and a certain small animal, not unlike a rabbit, called by our

people Pharaoh's mice, which during the summer season are found in great

abundance in the plains. They eat flesh of every description, horses,

camels, and even dogs, provided they are fat. "They drink mares' milk, which they prepare in such a manner that it

has the qualities and flavor of white wine. They term it in their

language kemurs. "Their women are not excelled in the world for chastity and decency

of conduct, nor for love and duty to their husbands. Infidelity to the

marriage bed is regarded by them as a vice not merely dishonorable, but

of the most infamous nature; while on the other hand it is admirable to

observe the loyalty of the husbands towards their wives, amongst whom,

although there are perhaps ten or twenty, there prevails a highly

laudable degree of quiet and union. "No offensive language is ever heard, their attention being fully

occupied with their traffic (as already mentioned) and their several

domestic employments, such as the provision of necessary food for the

family, the management of the servants, and the care of the children, a

common concern. "And the virtues of modesty and chastity in the wives are more

praiseworthy because the men are allowed the indulgence of taking as

many as they choose. Their expense to the husband is not great, and on

the other hand the benefit he derives from their trading, and from the

occupations in which they are constantly engaged, is considerable; on

which account when he receives a young woman in marriage, he pays a

dower to her parent. "The wife who is the first espoused has the privilege of superior

attention, and is held to be the most legitimate, which extends also to

the children borne by her. In consequence of this unlimited number of

wives, the offspring is more numerous than amongst any other people. "Upon the death of the father, the son may take to himself the wives

he leaves behind, with the exception of his own mother. They cannot take

their sisters to wife, but upon the death of their brothers they can

marry their sisters-in-law. Every marriage is solemnized with great

ceremony. These images, like many on this page, are illustrations from reprints

of Marco Polo's book over the years. They show the romanticization

that has surrounded the work since it's earliest publication.

This excerpt is about how feasts are held with the Khan presiding.

I especially like the treatment of people who step on the threshold,

considered to be unlucky just about everywhere. "And when the Great Kaan sits at table on any great court occasion,

it is in this fashion. His table is elevated a good deal above the

others, and he sits at the north end of the hall, looking towards the

south, with his chief wife beside him on the left. 'On his right sit his sons and his nephews, and other kinsmen of the

Blood Imperial, but lower, so that their heads are on a level with the

Emperor's feet. And then the other Barons sit at other tables lower

still. So also with the women; for all the wives of the Lord's sons, and

of his nephews and other kinsmen, sit at the lower table to his right;

and below them again the ladies of the other Barons and Knights, each in

the place assigned by the Lord's orders. 'The tables are so disposed that the Emperor can see the whole of

them from end to end, many as they are. Further, you are not to suppose

that everybody sits at table; on the contrary, the greater part of the

soldiers and their officers sit at their meal in the hall on the

carpets. Outside the hall will be found more than 40,000 people; for

there is a great concourse of folk bringing presents to the Lord, or

come from foreign countries with curiosities. 'In a certain part of the hall near where the Great Kaan holds his

table, there is set a large and very beautiful piece of workmanship in

the form of a square coffer, or buffet, about three paces each way,

exquisitely wrought with figures of animals, finely carved and gilt. The

middle is hollow, and in it] stands a great vessel of pure gold, holding

as much as an ordinary butt; and at each corner of the great vessel is

one of smaller size of the capacity of a firkin, and from the former the

wine or beverage flavoured with fine and costly spices is drawn off into

the latter. 'And on the buffet aforesaid are set all the Lord's drinking vessels,

among which are certain pitchers of the finest gold, which are called

verniques, and are big enough to hold drink for eight or ten persons.

And one of these is put between every two persons, besides a couple of

golden cups with handles, so that every man helps himself from the

pitcher that stands between him and his neighbour. And the ladies are

supplied in the same way. The value of these pitchers and cups is

something immense; in fact, the Great Kaan has such a quantity of this

kind of plate, and of gold and silver in other shapes, as no one ever

before saw or heard tell of, or could believe. 'There are certain Barons specially deputed to see that foreigners,

who do not know the customs of the Court, are provided with places

suited to their rank; and these Barons are continually moving to and fro

in the hall, looking to the wants of the guests at table, and causing

the servants to supply them promptly with wine, milk, meat, or whatever

they lack. 'At every door of the hall (or, indeed, wherever the Emperor may be)

there stand a couple of big men like giants, one on each side, armed

with staves. Their business is to see that no one steps upon the

threshold in entering, and if this does happen, they strip the offender

of his clothes, and he must pay a forfeit to have them back again; or in

lieu of taking his clothes, they give him a certain number of blows. 'If they are foreigners ignorant of the order, then there are Barons

appointed to introduce them, and explain it to them. They think, in

fact, that it brings bad luck if any one touches the threshold. Howbeit,

they are not expected to stick at this in going forth again, for at that

time some are like to be the worse for liquor, and incapable of looking

to their steps. And you must know that those who wait upon the Great Kaan with his

dishes and his drink are some of the great Barons. They have the mouth

and nose muffled with fine napkins of silk and gold, so that no breath

nor odour from their persons should taint the dish or the goblet

presented to the Lord. 'And when the Emperor is going to drink, all the musical instruments,

of which he has vast store of every kind, begin to play. And when he

takes the cup all the Barons and the rest of the company drop on their

knees and make the deepest obeisance before him, and then the Emperor

doth drink. But each time that he does so the whole ceremony is

repeated. 'I will say nought about the dishes, as you may easily conceive that

there is a great plenty of every possible kind. But you should know that

in every case where a Baron or Knight dines at those tables, their wives

also dine there with the other ladies. 'And when all have dined and the tables have been removed, then come

in a great number of players and jugglers, adepts at all sorts of

wonderful feats, and perform before the Emperor and the rest of the

company, creating great diversion and mirth, so that everybody is full

of laughter and enjoyment. And when the performance is over, the company

breaks up and every one goes to his quarters. Marco Polo is one of the early Italian explorers and is honored in

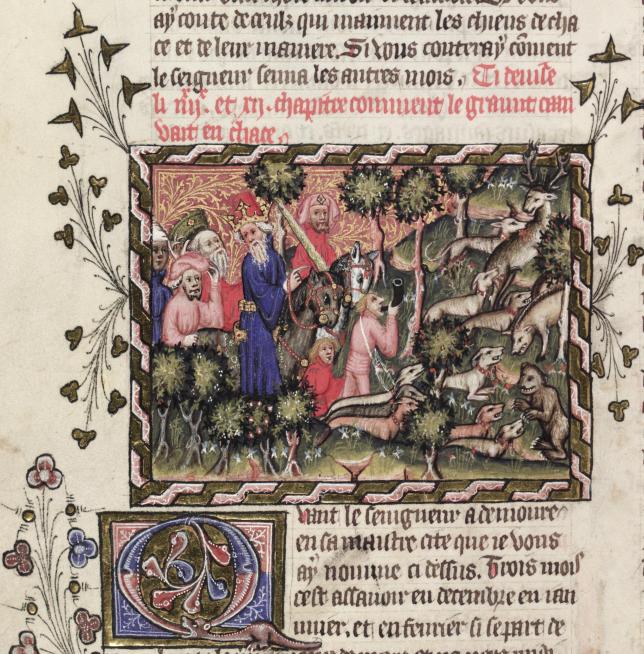

Italy as a pioneer. Marco describes how the Khan goes falconing after his three month stay in

the capital Cambaluc. "And so the Emperor follows this road that I have mentioned, leading

along in the vicinity of the Ocean Sea (which is within two days'

journey of his capital city, Cambaluc), and as he goes there is many a

fine sight to be seen, and plenty of the very best entertainment in

hawking; in fact, there is no sport in the world to equal it! 'The Emperor himself is carried upon four elephants in a fine chamber

made of timber, lined inside with plates of beaten gold, and outside

with lions' skins for he always travels in this way on his fowling

expeditions, because he is troubled with gout. 'He always keeps beside him a dozen of his choicest gerfalcons, and

is attended by several of his Barons, who ride on horseback alongside.

And sometimes, as they may be going along, and the Emperor from his

chamber is holding discourse with the Barons, one of the latter shall

exclaim: "Sire! Look out for Cranes!" 'Then the Emperor instantly has the top of his chamber thrown open,

and having marked the cranes he casts one of his gerfalcons, whichever

he pleases; and often the quarry is struck within his view, so that he

has the most exquisite sport and diversion, there as he sits in his

chamber or lies on his bed; and all the Barons with him get the

enjoyment of it likewise! 'So it is not without reason I tell you that I do not believe there

ever existed in the world or ever will exist, a man with such sport and

enjoyment as he has, or with such rare opportunities." Marco describes the Khan's tent-city when he goes hunting after his

three

months in the capital city. "And when he has travelled till he reaches a place called CACHAR

MODUN,there he finds his tents pitched, with the tents of his Sons, and

his Barons, and those of his Ladies and theirs, so that there shall be

full 10,000 tents in all, and all fine and rich ones. 'And I will tell you how his own quarters are disposed. The tent in

which he holds his courts is large enough to give cover easily to a

thousand souls. It is pitched with its door to the south, and the Barons

and Knights remain in waiting in it, whilst the Lord abides in another

close to it on the west side. When he wishes to speak with any one he

causes the person to be summoned to that other tent. 'Immediately behind the great tent there is a fine large chamber

where the Lord sleeps; and there are also many other tents and chambers,

but they are not in contact with the Great Tent as these are. 'The two audience-tents and the sleeping-chamber are constructed in

this way. Each of the audience-tents has three poles, which are of

spice-wood, and are most artfully covered with lions' skins, striped

with black and white and red, so that they do not suffer from any

weather. [ed. Here is an image of a yurt (Mongol tent) from today, to give an

idea of how large they can be.]

'All three apartments are also covered outside with similar skins of

striped lions, a substance that lasts for ever. And inside they are all

lined with ermine and sable, these two being the finest and most costly

furs in existence. For a robe of sable, large enough to line a mantle,

is worth 2000 bezants of gold, or 1000 at least, and this kind of skin

is called by the Tartars "The King of Furs." The beast itself is about

the size of a marten. These two furs of which I speak are applied and

inlaid so exquisitely, that it is really something worth seeing. 'All the tent-ropes are of silk. And in short I may say that those

tents, to wit the two audience-halls and the sleeping-chamber, are so

costly that it is not every king could pay for them. 'Round about these tents are others, also fine ones and beautifully

pitched, in which are the Emperor's ladies, and the ladies of the other

princes and officers. And then there are the tents for the hawks and

their keepers, so that altogether the number of tents there on the plain

is something wonderful. 'To see the many people that are thronging to and fro on every side

and every day there, you would take the camp for a good big city. For

you must reckon the Leeches, and the Astrologers, and the Falconers, and

all the other attendants on so great a company; and add that everybody

there has his whole family with him, for such is their custom." [ed. Here is an image of modern yurts set up for tourists in

Mongolia, including garbage container outside the front door.] The first link is the highest rated DVD/movie about Marco Polo from 1982

These are DVD documentaries.

Some biographies, books.

And for children.

This short Preface from a story about Marco Polo from 1896 by Noah

Brooks says it all: “The story of Marco Polo and his companions is

one of the most romantic and interesting of mediaeval or of modern

times. 'The manner of the return of the Polos long

after they ad been given up for dead, the subsequent adventures of

Marco Polo, the incredulity with which his book of travels was

received, the gradual and slow confirmations of the truth of his

reports as later explorations penetrated the mysterious Orient, and

the fact that he may be justly regarded as the founder of the

geography of Asia, have all combined to give to his narrative a

certain fascination, with which no other story of travel has been

invested. 'At first read for pure amusement, Marco Polo’s

book eventually became an authoritative account of regions of the

earth which were almost wholly unknown to Europe up to his time, and

some portions of which even now remain unexplored by Western

travelers.” I think the most striking things that we

discover

about Marco Polo, are that Marco: had a gregarious character, had great skill with people and languages,

was curious about people and their customs, that suggests

his book is the work of a

natural-born social-scientist, and he had a very study physique.

Marco, who took after his outgoing and

adventurous father, embraced the newness he discovered along his

journey, related to people as equals, and survived strenuous

travels, violence, illness and inclement weather that would have

stopped other men in their tracks and sent them packing back home

(several of their traveling companions did just that, others

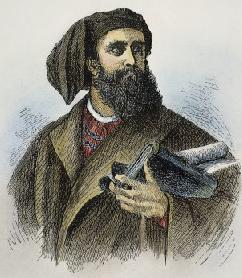

perished!). When you see representations of Marco Polo,

none made

during his lifetime, you see a sturdy hulk of a man

whom today we would say looks like a rugby player, or an adventurer. This physique seems the most likely. Only later, when Marco's story was

reprinted and illustrated for a mass audience, was his likeness

changed into a romanticized waif. I have links below

to free on-line copies of Marco Polo's book. It is the

famous Yule translation that comes in two volumes. You'll

find that the footnotes added by the translator to each chapter are

much longer than Marco's chapters, and they provide

fascinating information. But be warned, the first 69 pages or so, are

all about the translator! Then the next 150 pages are

background information about the times, the Polos, and Marco's book.

Then Marco's book begins with a prologue that offers an overview of

his father and uncle's travels, and his own travels with them and on

his own. After that, he discusses places he visited, one at a

time, over the two books. Marco's commentary, dictated to his

transcriber, is just as an Italian would speak to you. Many of

the phrases begin with "You should know..." which in Italian is

"Devi sapere...", a common way of beginning an explanation of

something to someone. The text is very colloquial, just as if

Marco were sitting there speaking to you. Marco explains

that he learned so much about the lives of the peoples he visited, because he

wanted to entertain the Khan with the details when he returned from

his missions. Marco had noticed that the other ambassadors

disappointed the Khan by their dry and spare accounts of their

journeys, so Marco kept notebooks as he traveled, noting down

things the Khan might not know. He brought these notebooks

home with him, and sent for them from prison, and referred to these notebooks

as he dictated his story. I provide

links below to Amazon.com

for movies and books about Marco Polo, and even a copy of his

Travels, in case you prefer a hard copy, or a paperbound book. But wouldn't it be nice to be able to read one

of the 80 or so hand-written copies believed to be have been

made? Or even one of the many, many early printed editions

with woodblock images? When visiting museums around the

world, be sure to check their manuscript sections. They

will surely have an early copy of The Travels of Marco Polo - Il

Milione. I link below to one

copy in the Bodleian Library that you can view on-line, and show

several of the illuminations that decorate that copy, written in

French. I report here a summary of the story of Marco Polo

(b.1254-d.1324) and

his father and uncle and their trips to the Far East. The

summary is written by the beloved American author Washington Irving

(b.1783-d.1859) and was included in his biography of Christopher

Columbus. Washington Irving Home,

Tarrytown Here begin Washington Irving's words: "The travels of Marco Polo, or Paolo [ ed.

the family uses both when writing their names], furnish a

key to many parts of the voyages and speculations of Columbus, which

without it would hardly be comprehensible. Marco Polo was a native of Venice, who, in the

thirteenth century, made a journey into the remote, and, at that

time, unknown regions of the East, and filled all Christendom with

curiosity by his account of the countries he had visited. He was preceded in his travels by his father

Nicholas and his uncle Maffeo Polo. These two brothers were of an

illustrious family in Venice, and embarked, about the year 1255, on

a commercial voyage to the East. Having traversed the Mediterranean and through

the Bosphorus, they stopped for a short time at Constantinople,

which city had recently been wrested from the Greeks by the joint

arms of France and Venice. [ed. The Polos, together with their

older brother, ran a trading business with offices in Venice,

Constantinople and Soldaia on the Black Sea] Here they disposed of their Italian

merchandise, and, having purchased a stock of jewelry, departed on

an adventurous expedition to trade with the western Tartars, who,

having overrun many parts of Asia and Europe, were settling and

forming cities in the vicinity of the Wolga. After traversing the Euxine [ed. Black Sea, or

Great Sea] to Soldaia, (at

present Sudak,) a port in the Crimea, they continued on, by land and

water, until they reached the military court, or rather camp, of a

Tartar prince, named Barkah, a descendant of Ghengis Khan, into

whose hands they confided all their merchandise.

The barbaric chieftain, while he was dazzled by

their precious commodities, was flattered by the entire confidence

in his justice manifested by these strangers. He repaid them with

princely munificence, and loaded them with favors during a year that

they remained at his court. A war breaking out between their patron and his

cousin Hulagu, chief of the eastern Tartars, and Barkah being

defeated, the Polos were embarrassed how to extricate themselves

from the country and return home in safety. The road to Constantinople being cut off by the

enemy, they took a circuitous route, round the head of the Caspian

Sea, and through the deserts of Transoxiana, until they arrived in

the city of Bokhara, where they resided for three years. While here there arrived a Tartar nobleman who

was on an embassy from the victorious Hulagu to his brother the

Grand Khan. The ambassador became acquainted with the Venetians, and

finding them to be versed in the Tartar tongue and possessed of

curious and valuable knowledge, he prevailed upon them to accompany

him to the court of the emperor, situated, as they supposed, at the

very extremity of the East. After a march of several months, being delayed

by snow-storms and inundations, they arrived at the court of Cublai,

otherwise called the Great Khan, which signifies King of Kings,

being the sovereign potentate of the Tartars. This magnificent prince received them with

great distinction; he made inquiries about the countries and princes

of the West, their civil and military government, and the manners

and customs of the Latin nation. Above all, he was curious on the

subject of the Christian religion. He was so much struck by their replies, that

after holding a council with the chief persons of his kingdom, he

entreated the two brothers to go on his part as ambassadors to the

pope, to entreat him to send a hundred learned men well instructed

in the Christian faith, to impart a knowledge of it to the sages of

his empire. He also entreated them to bring him a little oil from

the lamp of our Saviour, in Jerusalem, which he concluded must have

marvelous virtues.

It has been supposed, and with great reason,

that under this covert of religion, the shrewd Tartar sovereign

veiled motives of a political nature. The influence of the pope in

promoting the crusades had caused his power to be known and

respected throughout the East; it was of some moment, therefore, to

conciliate his good-will. Cublai Khan had no bigotry nor devotion to

any particular faith, and probably hoped, by adopting Christianity,

to make it a common cause between himself and the warlike princes of

Christendom, against his and their inveterate enemies, the soldan of

Egypt and the Saracens. [ed. The Pope held the same hope when

he heard of the Khan's overtures] Having written letters to the pope in the

Tartar language, he delivered them to the Polos, and appointed one

of the principal noblemen of his court to accompany them in their

mission.

On their taking leave he furnished them with a tablet of

gold on which was engraved the royal arms; this was to serve as a

passport, at sight of which the governors of the various provinces

were to entertain them, to furnish them with escorts through

dangerous places, and render them all other necessary services at

the expense of the Great Khan. [ed. These tablets, or royal bulls to

use the Vatican term, were common in the Mongol empire, and were

indeed a passport for the bearer.] They had scarce proceeded twenty miles, when

the nobleman who accompanied them fell ill, and they were obliged to

leave him, and continue on their route. Their golden passport procured them every

attention and facility throughout the dominions of the Great Khan.

They arrived safely at Acre, in April, 1269.

[ed. Palestine's gateway to the Levant and a trading city during

Mediaeval Times, with offices and markets for the major Italian

city-states.]

Here they received news of the recent death of Pope Clement IV, at

which they were much grieved, fearing it would cause delay in their

mission.

There was at that time in Acre a legate of the

holy chair, Tebaldo di Vesconti, of Placentia, to whom they gave an

account of their embassy. He heard them with great attention and

interest, and advised them to await the election of a new pope,

which must soon take place, before they proceeded to Rome on their

mission. They determined in the interim to make a visit

to their families, and accordingly departed for Negropont, and

thence to Venice, where great changes had taken place in their

domestic concerns, during their long absence. The wife of Nicholas,

whom he had left pregnant, had died, in giving birth to a son, who

had been named Marco. As the contested election for the new pontiff

remained pending for two years, they were uneasy, lest the emperor

of Tartary should grow impatient at so long a postponement of the

conversion of himself and his people; they determined, therefore,

not to wait the election of a pope, but to proceed to Acre, and get

such dispatches and such ghostly ministry for the Grand Khan, as the

legate could furnish. On the second journey, Nicholas Polo took with

him his son Marco, who afterwards wrote an account of these travels. They were again received with great favor by

the legate Tebaldo, who, anxious for the success of their mission,

furnished them with letters to the Grand Khan, in which the

doctrines of the Christian faith were fully expounded. With these,

and with a supply of the holy oil from the sepulchre, they once more

set out in September, 1271, for the remote parts of Tartary. They had not long departed, when missives

arrived from Rome, informing the legate of his own election to the

holy chair. He took the name of Gregory X, and decreed that in

future, on the death of a pope, the cardinals should be shut up in

conclave until they elected a successor; a wise regulation, which

has since continued, enforcing a prompt decision, and preventing

intrigue.

Immediately on receiving intelligence of his

election, he dispatched a courier to the king of Armenia, requesting

that the two Venetians might be sent back to him, if they had not

departed. They joyfully returned, and were furnished with

new letters to the Khan. Two eloquent friars, also, Nicholas

Vincenti and Gilbert de Tripoli, were sent with them, with powers to

ordain priests and bishops and to grant absolution. They had

presents of crystal vases, and other costly articles, to deliver to

the Grand Khan; and thus well provided, they once more set forth on

their journey. Arriving in Armenia, they ran great risk of

their lives from the war which was raging, the soldan of Babylon

having invaded the country. They took refuge for some time with the

superior of a monastery. Here the two reverend fathers, losing all

courage to prosecute so perilous an enterprise, determined to

remain, and the Venetians continued their journey. They were a long time on the way, and exposed

to great hardships and sufferings from floods and snow-storms, it

being the winter season. At length they reached a town in the

dominions of the Khan. That potentate sent officers to meet them at

forty days' distance from the court, and to provide quarters for

them during their journey. He received them with great kindness, was

highly gratified with the result of their mission and with the

letters of the pope, and having received from them some oil from the

lamp of the holy sepulchre, he had it locked up, and guarded it as a

precious treasure. The three Venetians, father, brother and son,

were treated with such distinction by the Khan, that the courtiers

were filled with jealousy. Marco soon, however, made himself

popular, and was particularly esteemed by the emperor. He acquired

the four principal languages of the country [ed. Persian, Mongolian,

Uighur, Arabic], and was of such

remarkable capacity, that, notwithstanding his youth, the Khan

employed him in missions and services of importance, in various

parts of his dominions, some to the distance of even six months'

journey. On these expeditions he was industrious in

gathering all kinds of information respecting that vast empire; and

from notes and minutes made for the satisfaction of the Grand Khan,

he afterwards composed the history of his travels. After about seventeen years' residence in the

Tartar court the Venetians felt a longing to return to their native

country. Their patron was advanced in age and could not survive much

longer, and after his death, their return might be difficult, if not

impossible. They applied to the Grand Khan for permission to depart,

but for a time met with a refusal, accompanied by friendly

upbraidings. At length a singular train of events operated

in their favor; an embassy arrived from a Mogul Tartar prince, who

ruled in Persia, and who was grand-nephew to the emperor. The object

was to entreat, as a spouse, a princess of the imperial lineage.

[ed. His wife had died, and made him promise to remarry a woman from

her same family.] A

granddaughter of Cublai Klian, seventeen years of age, and of great

beauty and accomplishments, was granted to the prayer of the prince,

and departed for Persia with the ambassadors, and with a splendid

retinue, but after traveling for some months, was obliged to return

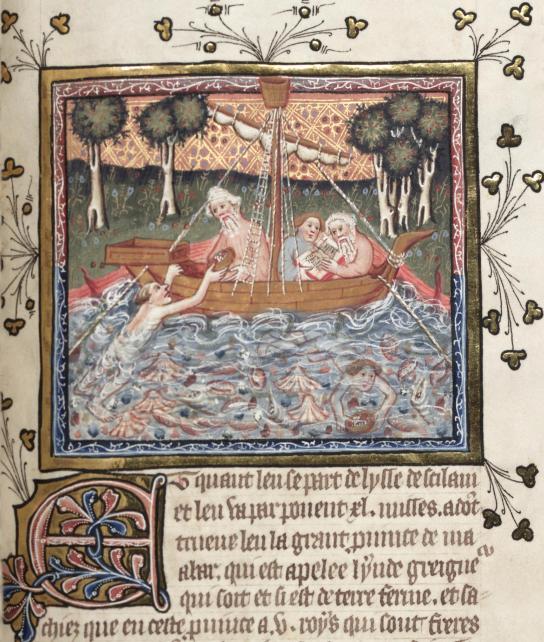

on account of the distracted state of the country. The ambassadors despaired of conveying the

beautiful bride to the arms of her expecting bridegroom, when Marco

Polo returned from a voyage to certain of the Indian islands. His

representations of the safety of a voyage in those seas, and his

private instigations, induced the ambassadors to urge the Grand Khan

for permission to convey the princess by sea to the gulf of Persia,

and that the Christians might accompany them, as being best

experienced in maritime affairs. Cublai Khan consented with great reluctance,

and a splendid fleet was fitted out and victualed for two years,

consisting of fourteen ships of four masts, some of which had crews

of two hundred and fifty men. On parting with the Venetians the munificent

Khan gave them rich presents of jewels, and made them promise to

return to him after they had visited their families. He authorized

them to act as his ambassadors to the principal courts of Europe,

and, as on a former occasion, furnished them with tablets of gold,

to serve, not merely as passports, but as orders upon all commanders

in his territories for accommodations and supplies. They set sail therefore in the fleet with the

oriental princess and her attendants and the Persian ambassadors.

The ships swept along the coast of Cochin China, stopped for three

months at a port of the island of Sumatra near the western entrance

of the straits of Malacca, waiting for the change of the monsoon to

pass the bay of Bengal. [ed. Marco describes all the spices that

later lead to this area's devastation by the East India Company,

their conquest of the Spice Islands.] Traversing this vast expanse, they touched

at the island of Ceylon [ed. Sri Lanka] and then crossed the strait to the southern

part of the great peninsula of India. Thence sailing up the Pirate

coast, as it is called, the fleet entered the Persian gulf and

arrived at the famous port of Olmuz, [ed. Hormuz] where it is presumed the voyage

terminated, after eighteen months spent in traversing the Indian

seas. [ed. Marco says only 8 people survived the journey.] Unfortunately for the royal bride who was the

object of this splendid naval expedition, the bridegroom, the Mogul

king, had died some time before her arrival, leaving a son named

Ghazan, during whose minority the government was administered by his

uncle Kai-Khatu. According to the directions of the regent, the

princess was delivered to the youthful prince, son of her intended

spouse. He was at that time at the head of an army on the borders of

Persia. He was of a diminutive stature, but of a great soul, and, on

afterwards ascending the throne, acquired renown for his talents and

virtues. What became of the Eastern bride, who had traveled so far

in quest of a husband, is not known; but every thing favorable is to

be inferred from the character of Ghazan. [ed. Marco relates that

the journey was very difficult, but he, his father, and his uncle

survived along with the young princess, who looked upon them as her

three fathers.] The Polos remained some time in the court of

the regent, and then departed, with fresh tablets of gold given by

that prince, to carry them in safety and honor through his

dominions. As they had to traverse many countries where the traveler

is exposed to extreme peril, they appeared on their journeys as

Tartars of low condition, having converted all their wealth into

precious stones and sewn them up in the folds and linings of their

coarse garments. They had a long, difficult, and perilous

journey to Trebizond, whence they proceeded to Constantinople,

thence to Negropont, and, finally, to Venice, where they arrived in

1295, in good health, and literally laden with riches. [ed. Many

surmise that they arrived with Tartar servants, too, who helped them

bring home their riches, and who lived with the Polos in Venice.] Having heard

during their journey of the death of their old benefactor Cublai

Khan, they considered their diplomatic functions at an end, and also

that they were absolved from their promise to return to his

dominions. Ramusio, in his preface to the narrative of

Marco Polo, [ed. Ramusio edited the earliest edition of The Travels

to be made on a printing press, and wrote a long preface] gives a variety of particulars concerning their arrival,

which he compares to that of Ulysses. When they arrived at Venice,

they were known by nobody. So many years had elapsed since their

departure, without any tidings of them, that they were either

forgotten or considered dead. Besides, their foreign garb, the

influence of southern suns, and the similitude which men acquire to

those among whom they reside for any length of time, had given them

the look of Tartars rather than Italians. They repaired to their own house, which was a

noble palace, situated in the street of St. Giovanni Chrisostomo,

and was afterwards known by the name of la Corte de la Milione. [ed.

Actually, it was a new house they bought in Venice after their

return, that took on that name.] They

found several of their relatives still inhabiting it; but they were

slow in recollecting the travelers, not knowing of their wealth, and

probably considering them, from their coarse and foreign attire,

poor adventurers returned to be a charge upon their families. The Polos, however, took an effectual mode of

quickening the memories of their friends, and insuring themselves a

loving reception. They invited them all to a grand banquet. When their guests arrived, they received them

richly dressed in garments of crimson satin of oriental fashion.

When water had been served for the washing of hands, and the company

were summoned to table, the travelers, who had retired, appeared

again in still richer robes of crimson damask. The first dresses

were cut up and distributed among the servants, being of such length

that they swept the ground, which, says Ramusio, was the mode in

those days, with dresses worn within doors.

Crimsom Damask After the first course, they again retired and

came in dressed in crimson velvet; the damask dresses being likewise

given to the domestics, and the same was done at the end of the

feast with their velvet robes, when they appeared in the Venetian

dress of the day. The guests were lost in astonishment, and could

not comprehend the meaning of this masquerade.

Crimsom Velvet Having dismissed all the attendants, Marco Polo

brought forth the coarse Tartar dresses in which they had arrived.

Slashing them in several places with a knife, and ripping open the

seams and lining, there tumbled forth rubies, sapphires, emeralds,

diamonds, and other precious stones, until the whole table glittered

with inestimable wealth, acquired from the munificence of the Grand

Khan, and conveyed in this portable form through the perils of their

long journey.

Rubies The company, observes Ramusio, were out of

their wits with amazement, and now clearly perceived what they had

at first doubted, that these in very truth were those honored and

valiant gentlemen the Polos, and, accordingly, paid them great

respect and reverence. The account of this curious feast is given by

Ramusio, on traditional authority, having heard it many times

related by the illustrious Gasparo Malipiero, a very ancient

gentleman, and a senator, of unquestionable veracity, who had it

from his father, who had it from his grandfather, and so on up to

the fountain-head. When the fame of this banquet and of the wealth

of the travelers came to be divulged throughout Venice, all the

city, noble and simple, crowded to do honor to the extraordinary

merit of the Polos. Maffeo, who was the eldest, was admitted to the

dignity of the magistracy.

Italian Merchant The youth of the city came every day to visit

and converse with Marco Polo, who was extremely amiable and

communicative. They were insatiable in their inquiries about Cathay

and the Grand Khan, which he answered with great courtesy, giving

details with which they were vastly delighted, and, as he always

spoke of the wealth of the Grand Khan in round numbers, they gave

him the name of Messer Marco Milioni. [ed. The Polo's purchased a palace in Venice

after their return, and because of Marco's storytelling, with lots

of large numbers of things owned by the Khan, the young men of

Venice gave Marco and the palace a nickname, Il Milione, The

Million, which also became a nickname for Marco's book.

The palace burned down in the 1600s and the Teatro Malibran was

built on it's foundations. The theatre exists today, close

to both the Rialto bridge and the Teatro Fenice.] Some months after their return, Lampa Doria,

commander of the Genoese navy, appeared in the vicinity of the

island of Curzola with seventy galleys. Andrea Dandolo, the Venetian

admiral, was sent against him. Marco Polo commanded a galley of the fleet. His

usual good fortune deserted him. Advancing the first in the line

with his galley, and not being properly seconded, he was taken

prisoner, thrown in irons, and carried to Genoa. Here he was

detained for a long time in prison, and all offers of ransom

rejected. [ed. It was usual at the time to earn money

from ransoming prisoners of war. Marco's father tried two

times, in long, drawn out negotiations through intermediaries to

ransom his son, but both attempts failed. In the end, Marco

was released because of the stature he built for himself while in

prison recounting his tales.] His imprisonment gave great uneasiness to his

father and uncle, fearing that he might never return. Seeing

themselves in this unhappy state, with so much treasure and no

heirs, they consulted together. They were both very old men; but Nicolo, observes Ramusio, was of a galliard complexion [ed. strong

or lively character]; it was determined he should take a wife. He

did so; and, to the wonder of his friends, in four years had three

children. In the meanwhile, the fame of Marco Polo's

travels had circulated in Genoa. His prison was daily crowded with

nobility, and he was supplied with every thing that could cheer him

in his confinement. A Genoese gentleman, who visited him every day,

at length prevailed upon him to write an account of what he had

seen. [ed. Marco says he agreed to dictate his stories to a

transcriber because he was tired of retelling them over and over

again to all his daily visitors.] He had his papers and journals sent to him from Venice, and,

with the assistance of his friend, or, as some will have it, his

fellow-prisoner [ed. Rustichello of Pisa], produced the work which afterwards made such noise

throughout the world. [ed. It was a 'best-seller' in a time when

books were copied by hand and decorated by hand. Later in the

early 1500s, Marco

Polo's book was reproduced on the new

printing presses, and was a real best-seller.] The merit of Marco Polo at length procured him

his liberty. He returned to Venice, where he found his father with a

house full of children. He took it in good part, followed the old

man's example, married, and had two daughters, Moretta and Fantina.

[ed. Actually, he had three daughters, all three mentioned by name

in his will, as well as his wife, Donata.]

The date of the death of Marco Polo is unknown

[ed. his will was made in 1323 when he was very ill, and he was dead

by the time 1324 came around];

he is supposed to have been, at the time, about seventy years of

age. [ed. Marco was a merchant trader, a business man for the

remaining years of his life, from 1300 to 1324.] On his death-bed he is said to have been exhorted by his

friends to retract what he had published, or, at least, to disavow

those parts commonly regarded as fictions. He replied indignantly

that so far from having exaggerated, he had not told one half of the

extraordinary things of which he had been an eye-witness. [ed.

It is only, really, during the Age of Exploration that the veracity

of Marco Polo's tales were accepted. Venice even has a very

old Carnival character based on Marco Polo, Marco Milione, who tells

tall tales.] [ed. It is interesting to note that in his last

will and testament, Marco frees his manservant, Peter a Tartar

(Mongol), and gives him a generous settlement. The will also

states that his manservant had a home of his own, provided by Marco

Polo. After living 26 years among Tartars, it seems Marco Polo

choose to have a Tartar for company until his last days. A few

years later, Peter was granted Venetian citizenship after living in

Venice for so long and behaving impeccably.] Marco Polo died without male issue. Of the

three sons of his father by the second marriage, one only had

children, viz. five sons and one daughter. The sons died without

leaving issue; the daughter inherited all her father's wealth, and

married into the noble and distinguished house of Trevesino. Thus

the male line of the Polos ceased in 1417, and the family name was

extinguished. Such are the principal particulars known of

Marco Polo; a man whose travels for a long time made a great noise

in Europe, and will be found to have had a great effect on modern

discovery. His splendid account of the extent, wealth, and

population of the Tartar territories filled every one with

admiration. The possibility of bringing all those regions under the

dominion of the church, and rendering the Grand Khan an obedient

vassal to the holy chair, was for a long time a favorite topic among

the enthusiastic missionaries of Christendom, and there were many

saints-errant who undertook to effect the conversion of this

magnificent infidel. Even at the distance of two centuries, when the

enterprises for the discovery of the new route to India had set all

the warm heads of Europe madding about these remote regions of the

East, the conversion of the Grand Khan became again a popular theme;

and it was too speculative and romantic an enterprise not to catch

the vivid imagination of Columbus. In all his voyages, he will be

found continually to be seeking after the territories of the Grand

Khan, and even after his last expedition, when nearly worn out by

age, hardships, and infirmities, he offered, in a letter to the

Spanish monarchs, written from a bed of sickness, to conduct any

missionary to the territories of the Tartar emperor, who would

undertake his conversion. The work of Marco Polo is stated by some to

have been originally written in Latin, though the most probable

opinion is that it was written in the Venetian dialect of the

Italian. Copies of it in manuscript were multiplied and rapidly

circulated; translations were made into various languages, until the

invention of printing enabled it to be widely diffused throughout

Europe. In the course of these translations and

successive editions, the original text, according to Purchas, has

been much vitiated, and it is probable many extravagances in numbers

and measurements with which Marco Polo is charged may be the errors

of translators and printers. When the work first appeared, it was considered

by some as made up of fictions and extravagances, and Vossius

assures us that even after the death of Marco Polo he continued to

be a subject of ridicule among the light and unthinking, insomuch

that he was frequently personated at masquerades by some wit or

droll, who, in his feigned character, related all kinds of

extravagant fables and adventures. His work, however, excited great attention

among thinking men, containing evidently a fund of information

concerning vast and splendid countries, before unknown to the

European world. Vossius assures us that it was at one time highly

esteemed by the learned. Francis Pepin, author of the Brandenburgh

version, styles Polo a man commendable for his piety, prudence, and

fidelity. Athanasius Kircher, in his account of China,

says that none of the ancients have described the kingdoms of the

remote East with more exactness. Various other learned men of past

times have borne testimony to his character, and most of the

substantial parts of his work have been authenticated by subsequent

travelers. The most able and ample vindication of Marco

Polo, however, is to be found in the English translation of his

work, with copious notes and commentaries, by William Marsden, F. R.

S. He has diligently discriminated between what Marco Polo relates

from his own observation, and what he relates as gathered from

others; he points out the errors that have arisen from

misinterpretations, omissions, or interpretations of translators,

and he claims all proper allowance for the superstitious coloring of

parts of the narrative from the belief, prevalent among the most

wise and learned of his day, in miracles and magic. After perusing the work of Mr. Marsden, the

character of Marco Polo rises in the estimation of the reader. It is

evident that his narration, as far as related from his own

observations, is correct, and that he had really traversed a great

part of Tartary and China, and navigated in the Indian seas. Some of the countries and many of the islands,

however, are evidently described from accounts given by others, and

in these accounts are generally found the fables which have excited

incredulity and ridicule. As he composed his work after his return

home, partly from memory and partly from memorandums, he was liable

to confuse what he had heard with what he had seen, and thus to give

undue weight to many fables and exaggerations which he had received

from others. Much had been said of a map brought from Cathay

by Marco Polo, which was conserved in the convent of San Michale de

Murano in the vicinity of Venice, and in which the Cape of Good Hope

and the island of Madagascar were indicated; countries which the

Portuguese claim the merit of having discovered two centuries

afterwards. It has been suggested also that Columbus had visited the

convent and examined this map, whence he derived some of his ideas

concerning the coast of India. According to Ramusio, however, who had been at

the convent, and was well acquainted with the prior, the map

preserved there was one copied by a friar from the original one of

Marco Polo, and many alterations and additions had since been made

by other hands, so that for a long time it lost all credit with

judicious people, until on comparing it with the work of Marco Polo

it was found in the main to agree with his descriptions. The Cape of

Good Hope was doubtless among the additions made subsequent to the

discoveries of the Portuguese.

Columbus makes no mention of this map, which he

most probably would have done had he seen it. He seems to have been

entirely guided by the one furnished by Paulo Toscanelli, and which

was apparently projected after the original map, or after the

descriptions of Marco Polo, and the maps of Ptolemy. When the attention of the world was turned

towards the remote parts of Asia in the 15th century, and the

Portuguese were making their attempts to circumnavigate Africa, the

narration of Marco Polo again rose to notice. This, with the travels

of Nicolo le Comte, the Venetian, and of Hieronimo da San Stefano, a

Genoese, are said to have been the principal lights by which the

Portuguese guided themselves in their voyages. Above all, the influence which the work of

Marco Polo had over the mind of Columbus, gives it particular

interest and importance. It was evidently an oracular work with him. He frequently quotes it, and on his voyages, supposing himself to be

on the Asiatic coast, he is continually endeavoring to discover the

islands and main-lands described in it, and to find the famous

Cipango. It is proper, therefore, to specify some of

those places, and the manner in which they are described by a

Venetian traveler, that the reader may more fully understand the

anticipations which were haunting the mind of Columbus in his

voyages among the West Indian islands, and along the coast of Terra

Firma. The winter residence of the Great Khan,