Candida Martinelli's Italophile Site

Main

Page This family-friendly site celebrates Italian culture for the enjoyment of children and

adults. Site-Overview

Venice

Grand Tour Short Story Below

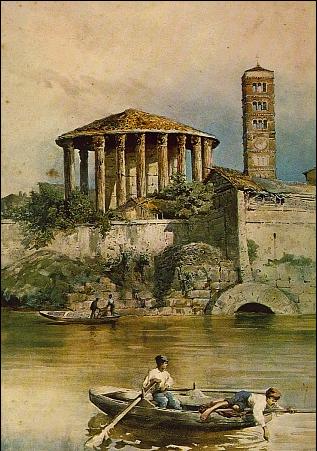

Temple of Hercules Victor (T.

Herculis Victoris). View

from Tiber. Cloaca

Maxima in the foreground. Painting

by Ettore Roesler Franz from the late 19th century.

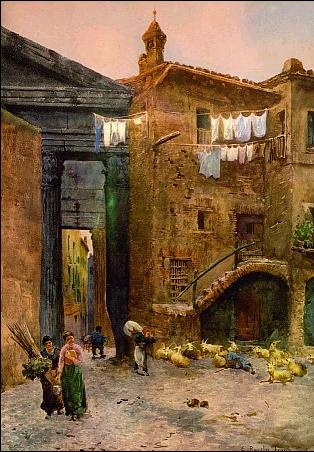

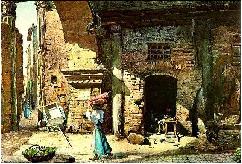

Porticus Octaviae.

The mediaeval house on the right still exists.

Painting by Ettore Roesler Franz from the late 19th century.

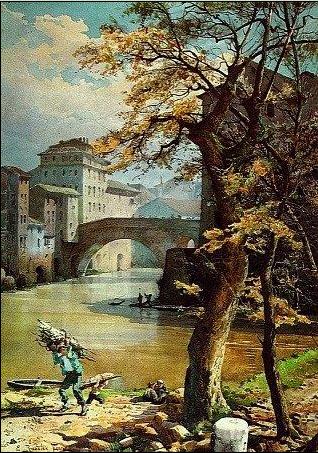

Isola

Tiberina. Painting

by Ettore Roesler Franz from the late 19th century. The art prints on this page were the sort of prints a

traveler doing The Grand Tour would take home from the

self-improving trip through continental Europe. The Grand Tour usually included some or all of these

locations: Paris, France The French Riviera Switzerland including Lake Constance and The Alps Venice, Florence, Rome, Naples and Pompeii in Italy,

and sometimes Calabria and Sicily German university towns Brussels, Bruges, Ghent in Belgium Amsterdam in The Netherlands The reasons to make The Grand Tour were: to see amazing art and architecture to perfect one's foreign languages to learn sophisticated continental manners to acquire sophisticated tastes.

Forum Romanum. Tabularium and the Temple of Saturn on the left.

Painting by Paolo Monaldi from the late 18th century. Early on the tour-ers,

or tourists as they're called now, were mainly young British men,

who added the prostitutes of continental Europe to their travel plans so

they could learn to make love, and to 'sow their wild oats', so they

would be ready to settle down once returned home. Some sowed their

oats for longer than their families had planned, and returned with

venereal diseases, if they returned at all.

Porticus

Octaviae.

Painting by Ettore Roesler Franz from the late 19th century. Later, young women were

sent on The Grand Tour from Britain, the U.S., Canada and Australia,

to acquire good taste, style and interests that would make them more

marriageable to well-educated young men. Even whole families

took the tour, while others saved it for their honeymoon voyage. In the days past, with a leisure class that lived off family

investments, the tour could last up to a year, but if the tourist

was very wealthy, and his family very patient, or he came all the way from Australia or New Zealand, it could last

years longer. Today's tourists generally have less preparation in the

classics and languages than their predecessors, but the wonder of Italy

remains. Perhaps more than anything, a Grand Tour of Italy

teaches the modern tourist humility in the face of such splendid

history, art, architecture, cooking, natural beauty and style. The Getty Museum has an

on-line exhibit to help us experience the 18th century Grand Tour in

Italy.

And below, I reproduce a short story by W. E.

Norris, Bianca, about a bored young man escorting his sister

on her Grand Tour. When they are stopped in Venice so she can

study the art, he lets himself get pulled into an elopement adventure.)

Isola Tiberina.

Painting by Ettore Roesler Franz from the late 19th century.

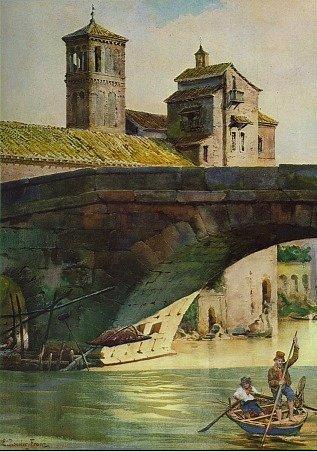

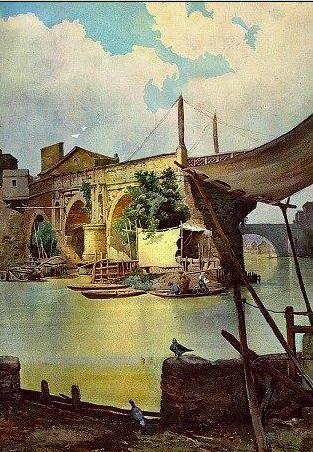

Pons

Aemilius. Painting

by Ettore Roesler Franz from the late 19th century.

(A bored young man escorts his sister on her Grand

Tour. When they are stopped in Venice so she can study the art, he

lets himself get pulled into an elopement adventure. I especially

enjoyed the slapstick humor when the elopement is discovered.

Candida)

Not long since, I was one among

a crowd of nobodies at a big official reception in Paris when

the Marchese and Marchesa di San Silvestro were announced.

There was a momentary hush; those about the doorway fell back to

let this distinguished couple pass, and some of us stood on

tiptoe to get a glimpse of them; for San Silvestro is a man of

no small importance in the political and diplomatic world, and

his wife enjoys quite a European fame for beauty and amiability,

having had opportunities of displaying both these attractive

gifts at the several courts where she has acted as Italian

ambassadress. They made their way quickly up the long

room,--she short, rather sallow, inclined toward embonpoint, but

with eyes whose magnificence was rivalled only by that of her

diamonds; he bald-headed, fat, gray-haired, covered with

orders,--and were soon out of sight. I followed them with a

sigh which caused my neighbour to ask me jocosely whether the

marchesa was an old flame of mine.

"Far from it," I answered.

"Only the sight of her reminded me of bygone days. Dear, dear

me! How time does slip on! It is fifteen years since I saw her

last.

I moved away, looking down

rather ruefully at the waistcoat to whose circumference fifteen

years have made no trifling addition, and wondering whether I

was really as much altered and aged in appearance as the

marchesa was.

Fifteen years--it is no such

very long time; and yet I dare say that the persons principally

concerned in the incident which I am about to relate have given

up thinking about it as completely as I had done, until the

sound of that lady's name, and the sight of her big black eyes,

recalled it to me, and set me thinking of the sunny spring

afternoon on which my sister Anne and I journeyed from Verona to

Venice, and of her naive exclamations of delight on finding

herself in a real gondola, gliding smoothly down the Grand

Canal. My sister Anne is by some years my senior. She is what

might be called an old lady now, and she certainly was an old

maid then, and had long accepted her position as such. Then, as

now, she habitually wore a gray alpaca gown, a pair of

gold-rimmed spectacles, gloves a couple of sizes too large for

her, and a shapeless, broad-leaved straw hat, from which a blue

veil was flung back and streamed out in the breeze behind her,

like a ship's ensign. Then, as now, she was the simplest, the

most kind-hearted, the most prejudiced of mortals; an

enthusiastic admirer of the arts, and given, as her own small

contribution thereto, to the production of endless water-colour

landscapes, a trifle woolly, indeed, as to outline, and somewhat

faulty as to perspective, but warm in colouring, and highly

thought of in the family. I believe, in fact, that it was

chiefly with a view to the filling of her portfolio that she had

persuaded me to take her to Venice; and, as I am

constitutionally indolent, I was willing enough to spend a few

weeks in the city which, of all cities in the world, is the best

adapted for lazy people. We engaged rooms at Danielli's, and

unpacked all our clothes, knowing that we were not likely to

make another move until the heat should drive us away.

The first few days, I remember,

were not altogether full of enjoyment for one of us. My

excellent Anne, who has all her brother's virtues, without his

failings, would have scouted the notion of allowing any dread of

physical fatigue to stand between her and the churches and

pictures which she had come all the way from England to admire;

and, as Venice was an old haunt of mine, she very excusably

expected me to act as cicerone to her, and allowed me but little

rest between the hours of breakfast and of the table d'hote.

At last, however, she conceived the modest and felicitous idea

of making a copy of Titian's "Assumption"; and, having obtained

the requisite permission for that purpose, set to work upon the

first of a long series of courageous attempts, all of which she

conscientiously destroyed when in a half-finished state. At

that rate it seemed likely that her days would be fully occupied

for some weeks to come; and I urged her to persevere, and not to

allow herself to be disheartened by a few brilliant failures;

and so she hurried away, early every morning, with her

paint-box, her brushes, and her block, and I was left free to

smoke my cigarettes in peace, in front of my favourite cafe on

the Piazza San Marco.

I was sitting there one morning,

watching, with half-closed eyes, the pigeons circling overhead

under a cloudless sky, and enjoying the fresh salt breeze that

came across the ruffled water from the Adriatic, when I was

accosted by one of the white-coated Austrian officers by whom

Venice was thronged in those days, and whom I presently

recognised as a young fellow named Von Rosenau, whom I had known

slightly in Vienna the previous winter. I returned his greeting

cordially, for I always like to associate as much as possible

with foreigners when I am abroad, and little did I foresee into

what trouble this fair-haired, innocent-looking youth was

destined to lead me.

I asked him how he liked Venice,

and he answered laughingly that he was not there from choice.

"I am in disgrace," he explained. "I am always in disgrace,

only this time it is rather worse than usual. Do you remember

my father, the general? No? Perhaps he was not in Vienna when

you were there. He is a soldier of the old school, and manages

his family as they tell me he used to manage his regiment in

former years, boasting that he never allowed a breach of

discipline to pass unpunished, and never will. Last year I

exceeded my allowance, and the colonel got orders to stop my

leave; this year I borrowed money, the whole thing was found

out, and I was removed from the cavalry, and put into a Croat

regiment under orders for Venice. Next year will probably see

me enrolled in the police; and so it will go on, I suppose, till

some fine morning I shall find myself driving a two-horse yellow

diligence in the wilds of Carinthia, and blowing a horn to let

the villagers know that the imperial and royal mail is

approaching.

After a little more conversation

we separated, but only to meet again, that same evening, on the

Piazza San Marco, whither I had wandered to listen to the band

after dinner, and where I found Von Rosenau seated with a number

of his brother officers in front of the principal cafe. These

gentlemen, to whom I was presently introduced, were unanimous in

complaining of their present quarters. Venice, they said, might

be all very well for artists and travellers; but viewed as a

garrison it was the dullest of places. There were no

amusements, there was no sport, and just now no society; for the

Italians were in one of their periodical fits of sulks, and

would not speak to, or look at, a German if they could possibly

avoid it. "They will not even show themselves when our band is

playing," said one of the officers, pointing toward the

well-nigh empty piazza. "As for the ladies, it is reported that

if one of them is seen speaking to an Austrian, she is either

assassinated or sent off to spend the rest of her days in a

convent. At all events, it is certain that we have none of us

any successes to boast of, except Von Rosenau, who has had an

affair, they say, only he is pleased to be very mysterious about

it.

"Where does she live, Von

Rosenau?" asked another. "Is she rich? Is she noble? Has she

a husband, who will stab you both? Or only a mother, who will

send her to a nunnery, and let you go free? You might gratify

our curiosity a little. It would do you no harm, and it would

give us something to talk about.

"Bah! He will tell you

nothing," cried a third. "He is afraid. He knows that there

are half a dozen of us who could cut him out in an hour.

"Von Rosenau," said a young

ensign, solemnly, "you would do better to make a clean breast of

it. Concealment is useless. Janovicz saw you with her in Santa

Maria della Salute the other day, and could have followed her

home quite easily if he had been so inclined.

"They were seen together on the

Lido, too. People who want to keep their secrets ought not to

be so imprudent.

"A good comrade ought to have no

secrets from the regiment.

"Come, Von Rosenau, we will

promise not to speak to her without your permission if you will

tell us how you managed to make her acquaintance.

The object of all these attacks

received them with the most perfect composure, continuing to

smoke his cigar and gaze out seaward, without so much as turning

his head toward his questioners, to whom he vouchsafed no reply

whatever. Probably, as an ex-hussar and a sprig of nobility, he

may have held his head a little above those of his present

brother officers, and preferred disregarding their familiarity

to resenting it, as he might have done if it had come from men

whom he considered on a footing of equality with himself. Such,

at least, was my impression; and it was confirmed by the

friendly advances which he made toward me, from that day forth,

and by the persistence with which he sought my society. I

thought he seemed to wish for some companion whose ideas had not

been developed exclusively in barrack atmosphere; and I, on my

side, was not unwilling to listen to the chatter of a lively,

good-natured young fellow, at intervals, during my long idle

days.

It was at the end of a week, I

think, or thereabouts, that he honoured me with his full

confidence. We had been sea-fishing in a small open boat which

he had purchased, and which he managed without assistance; that

is to say, that we had provided ourselves with what was

requisite for the pursuit of that engrossing sport, and that the

young count had gone through the form of dropping his line over

the side and pulling it up, baitless and fishless, from time to

time, while I had dispensed with even this shallow pretence of

employment, and had stretched myself out full length upon the

cushions which I had thoughtfully brought with me, inhaling the

salt-laden breeze, and luxuriating in perfect inaction, till

such time as it had become necessary for us to think of

returning homeward. My companion had been sighing portentously

every now and again all through the afternoon, and had

repeatedly given vent to a sound as though he had been about to

say something, and had as often checked himself, and fallen back

into silence. So that I was in a great measure prepared for the

disclosure that fell from him at length as we slipped before the

wind across the broad lagoon, toward the haze and blaze of

sunset which was glorifying the old city of the doges.

"Do you know," said he,

suddenly, "that I am desperately in love?" I said I had

conjectured as much; and he seemed a good deal surprised at my

powers of divination. "Yes," he resumed, "I am in love; and

with an Italian lady too, unfortunately. Her name is

Bianca,--the Signorina Bianca Marinelli,--and she is the most

divinely beautiful creature the sun ever shone upon.

"That," said I, "is of course.

"It is the truth; and when you

have seen her, you will acknowledge that I do not exaggerate. I

have known her nearly two months now. I became acquainted with

her accidentally--she dropped her handkerchief in a shop, and I

took it to her, and so we got to be upon speaking terms,

and--and--But I need not give you the whole history. We have

discovered that we are all the world to each other; we have

sworn to remain faithful to each other all our lives long; and

we renew the oath whenever we meet. But that, unhappily, is

very seldom! For her father, the Marchese Marinelli, scarcely

ever lets her out of his sight; and he is a sour, narrow-minded

old fellow, as proud as he is poor, an intense hater of all

Austrians; and if he were to discover our attachment, I shudder

to think of what the consequences might be.

"And your own father--the stern

old general of whom you told me--what would he say to it all?"

"Oh, he, of course, would not

hear of such a marriage for a moment. He detests and despises

the Venetians as cordially as the marchese abhors the

Tedeschi; and, as I am entirely dependent upon him, I should

not dream of saying a word to him about the matter until I was

married, and nothing could be done to separate me from Bianca.

"So that, upon the whole, you

appear to stand a very fair chance of starvation, if everything

turns out according to your wishes. And pray, in what way do

you imagine that I can assist you toward this desirable end?

For I take it for granted that you have some reason for letting

me into your secret.

Von Rosenau laughed

good-humouredly.

"You form conclusions quickly,"

he said. "Well, I will confess to you that I have thought

lately that you might be of great service to me without

inconveniencing yourself much. The other day, when you did me

the honour to introduce me to your sister, I was very nearly

telling her all. She has such a kind countenance; and I felt

sure that she would not refuse to let my poor Bianca visit her

sometimes. The old marchese, you see, would have no objection

to leaving his daughter for hours under the care of an English

lady; and I thought that perhaps when Miss Jenkinson went out to

work at her painting--I might come in.

"Fortunate indeed is it for

you," I said, "that your confidence in the kind countenance of

my sister Anne did not carry you quite to the point of divulging

this precious scheme to her. I, who know her pretty well, can

tell you exactly the course she would have pursued if you had.

Without one moment's hesitation, she would have found out the

address of the young lady's father, hurried off thither, and

told him all about it. Anne is a thoroughly good creature; but

she has little sympathy with love-making, still less with

surreptitious love-making, and she would as soon think of

accepting the part you are so good as to assign to her as of

forging a check.

He sighed, and said he supposed,

then, that they must continue to meet as they had been in the

habit of doing, but that it was rather unsatisfactory.

"It says something for your

ingenuity that you contrive to meet at all," I remarked.

"Well, yes, there are

considerable difficulties, because the old man's movements are

so uncertain; and there is some risk too, for, as you heard the

other day, we have been seen together. Moreover, I have been

obliged to tell everything to my servant Johann, who waylays the

marchese's housekeeper at market in the mornings, and finds out

from her when and where I can have an opportunity of meeting

Bianca. I would rather not have trusted him; but I could think

of no other plan.

"At any rate, I should have

thought you might have selected some more retired rendezvous

than the most frequented church in Venice.

He shrugged his shoulders. "I

wish you would suggest one within reach," he said. "There are

no retired places in this accursed town. But, in fact, we see

each other very seldom. Often for days together the only way in

which I can get a glimpse of her is by loitering about in my

boat in front of her father's house, and watching till she shows

herself at the window. We are in her neighborhood now, and it

is close upon the hour at which I can generally calculate upon

her appearing. Would you mind my making a short detour that way

before I set you down at your hotel?"

We had entered the Grand Canal

while Von Rosenau had been relating his love-tale, and some

minutes before he had lowered his sail and taken to the oars.

He now slewed the boat's head round abruptly, and we shot into a

dark and narrow waterway, and so, after sundry twistings and

turnings, arrived before a grim, time-worn structure, so hemmed

in by the surrounding buildings that it seemed as if no ray of

sunshine could ever penetrate within its walls.

"That is the Palazzo Marinelli,"

said my companion. "The greater part of it is let to different

tenants. The family has long been much too poor to inhabit the

whole of it, and now the old man only reserves himself four

rooms on the third floor. Those are the windows, in the far

corner; and there--no!--yes!--there is Bianca.

I brought my eyeglass to bear

upon the point indicated just in time to catch sight of a female

head, which was thrust out through the open window for an

instant, and then withdrawn with great celerity.

"Ah," sighed the count, "it is

you who have driven her away. I ought to have remembered that

she would be frightened at seeing a stranger. And now she will

not show herself again, I fear. Come; I will take you home.

Confess now--is she not more beautiful than you expected?"

"My dear sir, I had hardly time

to see whether she was a man or a woman; but I am quite willing

to take your word for it that there never was anybody like

her.

"If you would like to wait a

little longer--half an hour or so--she might put her head

out again," said the young man, wistfully.

"Thank you very much; but my

sister will be wondering why I do not come to take her down to

the table d'hote. And besides, I am not in love myself,

I may perhaps be excused for saying that I want my dinner.

"As you please," answered the

count, looking the least bit in the world affronted; and so he

pulled back in silence to the steps of the hotel, where we

parted.

I don't know whether Von Rosenau

felt aggrieved by my rather unsympathetic reception of his

confidence, or whether he thought it useless to discuss his

projects further with one who could not or would not assist him

in carrying them out; but although we continued to meet daily,

as before, he did not recur to the interesting subject, and it

was not for me to take the initiative in doing so. Curiosity, I

confess, led me to direct my gondolier more than once to the

narrow canal over which the Palazzo Martinelli towered; and on

each occasion I was rewarded by descrying, from the depths of

the miniature mourning-coach which concealed me, the faithful

count, seated in his boat and waiting in patient faith, like

another Ritter Toggenburg, with his eyes fixed upon the corner

window; but of the lady I could see no sign. I was rather

disappointed at first, as day after day went by and my young

friend showed no disposition to break the silence in which he

had chosen to wrap himself; for I had nothing to do in Venice,

and I thought it would have been rather amusing to watch the

progress of this incipient romance. By degrees, however, I

ceased to trouble myself about it; and at the end of a fortnight

I had other things to think of, in the shape of plans for the

summer, my sister Anne having by that time satisfied herself

that, all things considered, Titian's "Assumption" was a little

too much for her.

It was Captain Janovicz who

informed me casually one evening that Von Rosenau was going away

in a few days on leave, and that he would probably be absent for

a considerable time.

"For my own part," remarked my

informant, "I shall be surprised if we see him back in the

regiment at all. He was only sent to us as a sort of punishment

for having been a naughty boy, and I suppose now he will be

forgiven, and restored to the hussars.

"So much for undying love,"

thinks I, with a cynical chuckle. "If there is any gratitude in

man, that young fellow ought to be showering blessings on me for

having refused to hold the noose for him to thrust his head

into.

Alas! I knew not of what I was

speaking. I had not yet heard the last of Herr von Rosenau's

entanglement, nor was I destined to escape from playing my part

in it. The very next morning, after breakfast, as I was poring

over a map of Switzerland, "Murray" on my right hand and

"Bradshaw" on my left, his card was brought to me, together with

an urgent request that I would see him immediately and alone;

and before I had had time to send a reply, he came clattering

into the room, trailing his sabre behind him, and dropped into

the first arm-chair with a despairing self-abandonment which

shook the house to its foundations.

"Mr. Jenkinson," said he, "I am

a ruined man!"

I answered rather drily that I

was very sorry to hear it. If I must confess the truth, I

thought he had come to borrow money of me.

"A most cruel calamity has

befallen me," he went on; "and unless you will consent to help

me out of it--"

"I am sure I shall be delighted

to do anything in my power," I interrupted, apprehensively; "but

I am afraid--"

"You cannot refuse me till you

have heard what I have to say. I am aware that I have no claim

whatever upon your kindness; but you are the only man in the

world who can save me, and, whereas the happiness of my whole

life is at stake, the utmost you can have to put up with will be

a little inconvenience. Now I will explain myself in as few

words as possible, because I have only a minute to spare. In

fact, I ought to be out on the ramparts at this moment. You

have not forgotten what I told you about myself and the

Signorina Martinelli, and how we had agreed to seize the first

opportunity that offered to be privately married, and to escape

over the mountains to my father's house, and throw ourselves

upon his mercy?"

"I don't remember your having

mentioned any such plan.

"No matter--so it was. Well,

everything seemed to have fallen out most fortunately for us. I

found out some time ago that the marchese would be going over to

Padua this evening on business, and would be absent at least one

whole day, and I immediately applied for my leave to begin

tomorrow. This I obtained at once through my father, who now

expects me to be with him in a few days, and little knows that I

shall not come alone. Johann and the marchese's housekeeper

arranged the rest between them. I was to meet my dear Bianca

early in the morning on the Lido; thence we were to go by boat

to Mestre, where a carriage was to be in waiting for us; and the

same evening we were to be married by a priest, to whom I have

given due notice, at a place called Longarone. And so we should

have gone on, across the Ampezzo Pass homeward. Now would you

believe that all this has been defeated by a mere freak on the

part of my colonel? Only this morning, after it was much too

late to make any alteration in our plans, he told me that he

should require me to be on duty all today and tomorrow, and that

my leave could not begin until the next day. Is it not

maddening? And the worst of it is that I have no means of

letting Bianca know of this, for I dare not send a message to

the palazzo, and there is no chance of my seeing her myself; and

of course she will go to the Lido tomorrow morning, and will

find no one there. Now, my dear Mr. Jenkinson--my good, kind

friend--do you begin to see what I want you to do for me?"

"Not in the very least.

"No? But it is evident enough.

Now listen. You must meet Bianca tomorrow morning; you explain

to her what has happened; you take her in the boat, which will

be waiting for you, to Mestre; you proceed in the

travelling-carriage, which will also be waiting for you, to

Longarone; you see the priest, and appoint with him for the

following evening; and the next day I arrive, and you return to

Venice. Is that clear?"

The volubility with which this

programme was enunciated so took away my breath that I scarcely

realised its audacity.

"You will not refuse; I am sure

you will not," said the count, rising and hooking up his sword,

as if about to depart.

"Stop, stop!" I exclaimed. "You

don't consider what you are asking. I can't elope with young

women in this casual sort of way. I have a character--and a

sister. How am I to explain all this to my sister, I should

like to know?"

"Oh, make any excuse you can

think of to her. Now, Mr. Jenkinson, you know there cannot be

any real difficulty in that. You consent then? A thousand,

thousand thanks! I will send you a few more instructions by

letter this evening. I really must not stay any longer now.

Good-bye.

"Stop! Why can't your servant

Johann do all this instead of me?"

"Because he is on duty like

myself. Good-bye.

"Stop! Why can't you postpone

your flight for a day? I don't so much mind meeting the young

lady and telling her all about it.

"Quite out of the question, my

dear sir. It is perfectly possible that the marchese may return

from Padua tomorrow night, and what should we do then? No, no;

there is no help for it. Good-bye.

"Stop! Hi! Come back!"

But it was too late. My

impetuous visitor was down the staircase and away before I had

descended a single flight in pursuit, and all I could do was to

return to my room and register a vow within my own heart that I

would have nothing to do with this preposterous scheme.

Looking back upon what followed

across the interval of fifteen years, I find that I can really

give no satisfactory reason for my having failed to adhere to

this wise resolution. I had no particular feeling of friendship

for Von Rosenau; I did not care two straws about the Signorina

Bianca, whom I had never seen; and certainly I am not, nor ever

was, the sort of person who loves romantic adventures for their

own sake. Perhaps it was good-nature, perhaps it was only an

indolent shrinking from disobliging anybody, that influenced

me--it does not much matter now. Whatever the cause of my

yielding may have been, I did yield. I prefer to pass over in

silence the doubts and hesitations which beset me for the

remainder of the day; the arrival, toward evening, of the

piteous note from Von Rosenau, which finally overcame my weak

resistance to his will; and the series of circumstantial false

statements (I blush when I think of them) by means of which I

accounted to my sister for my proposed sudden departure.

Suffice it to say that, very

early on the following morning, there might have been seen,

pacing up and down the shore on the seaward side of the Lido,

and peering anxiously about him through an eyeglass, as if in

search of somebody or something, the figure of a tall, spare

Englishman, clad in a complete suit of shepherd's tartan, with a

wide-awake on his head, a leather bag slung by a strap across

his shoulder, and a light coat over his arm. Myself, in point

of act, in the travelling-costume of the epoch.

I was kept waiting a long

time--longer than I liked; for, as may be supposed, I was most

anxious to be well away from Venice before the rest of the world

was up and about; but at length there appeared, round the corner

of a long white wall which skirted the beach, a little lady,

thickly veiled, who, on catching sight of me, whisked round, and

incontinently vanished. This was so evidently the fair Bianca

that I followed her without hesitation, and almost ran into her

arms as I swung round the angle of the wall behind which she had

retreated. She gave a great start, stared at me, for an

instant, like a startled fawn, and then took to her heels and

fled. It was rather ridiculous; but there was nothing for me to

do but to give chase. My legs are long, and I had soon headed

her round.

"I presume that I have the

honour of addressing the Signorina Marinelli?" I panted, in

French, as I faced her, hat in hand.

She answered me by a piercing

shriek, which left no room for doubt as to her identity.

"For the love of Heaven, don't

do that!" I entreated, in an agony. "You will alarm the whole

neighbourhood and ruin us both. Believe me, I am only here as

your friend, and very much against my own wishes. I have come

on the part of Count Albrecht von Rosenau, who is unable to come

himself, because--"

Here she opened her mouth with

so manifest an intention of raising another resounding screech

that I became desperate, and seized her by the wrists in my

anxiety. "Sgridi ancora una volta," says I, in the

purest lingua Toscana, "e la lascero qui--to get

out of this mess as best you can--cosi sicuro che il mio nome

e Jenkinsono!"

To my great relief she began to

laugh. Immediately afterward, however, she sat down on the

shingle and began to cry. It was too vexatious: what on earth

was I to do?

"Do you understand English?" I

asked, despairingly.

She shook her head, but sobbed

out that she spoke French; so I proceeded to address her in that

language.

"Signorina, if you do not get up

and control your emotion, I will not be answerable for the

consequences. We are surrounded by dangers of the

most--compromising description; and every moment of delay must

add to them. I know that the officers often come out here to

bathe in the morning; so do many of the English people from

Danielli's. If we are discovered together there will be such a

scandal as never was, and you will most assuredly not become

Countess von Rosenau. Think of that, and it will brace your

nerves. What you have to do is to come directly with me to the

boat which is all ready to take us to Mestre. Allow me to carry

your hand-bag.

Not a bit of it! The signorina

refused to stir.

"What is it? Where is Alberto?

What has happened?" she cried. "You have told me nothing.

"Well, then, I will explain," I

answered, impatiently. And I explained accordingly.

But, dear me, what a fuss she

did make over it all! One would have supposed, to hear her,

that I had planned this unfortunate complication for my own

pleasure, and that I ought to have been playing the part of a

suppliant instead of that of a sorely tried benefactor. First

she was so kind as to set me down as an imposter, and was only

convinced of my honesty when I showed her a letter in the

beloved Alberto's handwriting. Then she declared that she could

not possibly go off with a total stranger. Then she discovered

that, upon further consideration, she could not abandon poor

dear papa in his old age. And so forth, and so forth, with a

running accompaniment of tears and sobs. Of course she

consented at last to enter the boat; but I was so exasperated by

her silly behaviour that I would not speak to her, and had

really scarcely noticed whether she was pretty or plain till we

were more than half-way to Mestre. But when we had hoisted our

sail, and were running before a fine, fresh breeze toward the

land, and our four men had shipped their oars and were

chattering and laughing under their breath in the bows, and the

first perils of our enterprise seemed to have been safely

surmounted, my equanimity began to return to me, and I stole a

glance at the partner of my flight, who had lifted her veil, and

showed a pretty, round, childish face, with a clear, brown

complexion, and a pair of the most splendid dark eyes it has

ever been my good fortune to behold. There were no tears in

them now, but a certain half-frightened, half-mischievous light

instead, as if she rather enjoyed the adventure, in spite of its

inauspicious opening. A very little encouragement induced her

to enter into conversation, and ere long she was prattling away

as unrestrainedly as if we had been friends all our lives. She

asked me a great many questions. What was I doing in Venice?

Had I known Alberto long? Was I very fond of him? Did I think

that the old Count von Rosenau would be very angry when he heard

of his son's marriage? I answered her as best I could, feeling

very sorry for the poor little soul, who evidently did not in

the least realise the serious nature of the step which she was

about to take; and she grew more and more communicative. In the

course of a quarter of an hour I had been put in possession of

all the chief incidents of her uneventful life.

I had heard how she had lost her

mother when she was still an infant; how she had been educated

partly by two maiden aunts, partly in a convent at Verona; how

she had latterly led a life of almost complete seclusion in the

old Venetian palace; how she had first met Alberto; and how,

after many doubts and misgivings, she had finally been prevailed

upon to sacrifice all for his sake, and to leave her father,

who,--stern, severe, and suspicious, though he had always been

generous to her,--had tried to give her such small pleasures as

his means and habits would permit. She had a likeness of him

with her, she said,--perhaps I might like to see it. She dived

into her travelling-bag as she spoke, and produced from thence a

full-length photograph of a tall, well-built gentleman of sixty

or thereabouts, whose gray hair, black moustache, and intent,

frowning gaze made up an ensemble more striking than attractive.

"Is he not handsome--poor papa?"

she asked.

I said the marchese was

certainly a very fine-looking man, and inwardly thanked my stars

that he was safely at Padua; for looking at the breadth of his

chest, the length of his arm, and the somewhat forbidding cast

of his features, I could not help perceiving that "poor papa"

was precisely one of those persons with whom a prudent man

prefers to keep friends than to quarrel.

And so, by the time that we

reached Mestre, we had become quite friendly and intimate, and

had half forgotten, I think, the absurd relation in which we

stood toward each other. We had rather an awkward moment when

we left the boat and entered our travelling-carriage; for I need

scarcely say that both the boatmen and the grinning vetturino

took me for the bridegroom whose place I temporarily occupied,

and they were pleased to be facetious in a manner which was very

embarrassing to me, but which I could not very well check.

Moreover, I felt compelled so far to sustain my assumed

character as to be specially generous in the manner of a

buona mano to those four jolly watermen, and for the first

few miles of our drive I could not help remembering this

circumstance with some regret, and wondering whether it would

occur to Von Rosenau to reimburse me.

Probably our coachman thought

that, having a runaway couple to drive, he ought to make some

pretence, at least, of fearing pursuit; for he set off at such a

furious pace that our four half-starved horses were soon beat,

and we had to perform the remainder of the long, hot, dusty

journey at a foot's pace. I have forgotten how we made the time

pass. I think we slept a good deal. I know we were both very

tired and a trifle cross when in the evening we reached

Longarone, a small, poverty-stricken village, on the verge of

that dolomite region which, in these latter days, has become so

frequented by summer tourists.

Tourists usually leave in their

wake some of the advantages as well as the drawbacks of

civilisation; and probably there is now a respectable hotel at

Longarone. I suppose, therefore, that I may say, without risk

of laying myself open to an action for slander, that a more

filthy den than the osteria before which my charge and I

alighted no imagination, however disordered, could conceive. It

was a vast, dismal building, which had doubtless been the palace

of some rich citizen of the republic in days of yore, but which

had now fallen into dishonoured old age. Its windows and

outside shutters were tightly closed, and had been so,

apparently, from time immemorial; a vile smell of rancid oil and

garlic pervaded it in every part; the cornices of its huge, bare

rooms were festooned with blackened cobwebs, and the dust and

dirt of ages had been suffered to accumulate upon the stone

floors of its corridors. The signorina tucked up her petticoats

as she picked her way along the passages to her bedroom, while I

remained behind to order dinner of the sulky, black-browed

padrona to whom I had already had to explain that my companion

and I were not man and wife, and who, I fear, had consequently

conceived no very high opinion of us. Happily the priest had

already been warned by telegram that his service would not be

required until the morrow; so I was spared the nuisance of an

interview with him.

After a time we sat down to our

tκte-ΰ-tκte dinner. Such a dinner! Even after a lapse of all

these years I am unable to think of it without a shudder. Half

famished though we were, we could not do much more than look at

the greater part of the dishes which were set before us; and the

climax was reached when we were served with an astonishing

compote, made up, so far as I was able to judge, of equal

proportions of preserved plums and mustard, to which vinegar and

sugar had been superadded. Both the signorina and I partook of

this horrible mixture, for it really looked as if it might be

rather nice; and when, after the first mouthful, each of us

looked up, and saw the other's face of agony and alarm, we burst

into a simultaneous peal of laughter. Up to that moment we had

been very solemn and depressed; but the laugh did us good, and

sent us to bed in somewhat better spirits; and the malignant

compote at least did us the service of effectually banishing our

appetite.

I forbear to enlarge upon the

horrors of the night. Mosquitos, and other insects, which, for

some reason or other, we English seldom mention, save under a

modest pseudonym, worked their wicked will upon me till daybreak

set me free; and I presume that the fair Bianca was no better

off, for when the breakfast hour arrived I received a message

from her to the effect that she was unable to leave her room.

I was sitting over my dreary

little repast, wondering how I should get through the day, and

speculating upon the possibility of my release before nightfall,

and I had just concluded that I must make up my mind to face

another night with the mosquitos and their hardy allies, when,

to my great joy, a slatternly serving-maid came lolloping into

the room, and announced that a gentleman styling himself "il

Conte di Rosenau" had arrived and demanded to see me

instantly. Here was a piece of unlooked-for good fortune! I

jumped up, and flew to the door to receive my friend, whose

footsteps I already heard on the threshold.

"My dear, good soul!" I cried,

"this is too delightful! How did you manage----"

The remainder of my sentence

died away upon my lips; for, alas! it was not the missing

Alberto whom I had nearly embraced, but a stout, red-faced,

white-moustached gentleman, who was in a violent passion,

judging by the terrific salute of Teutonic expletives with which

he greeted my advance. Then he, too, desisted as suddenly as I

had done, and we both fell back a few paces, and stared at each

other blankly. The new-comer was the first to recover himself.

"This is some accursed mistake,"

said he, in German.

"Evidently," said I.

"But they told me that you and

an Italian young lady were the only strangers in the house.

"Well, sir," I said, "I can't

help it if we are. The house is not of a kind likely to attract

strangers; and I assure you that, if I could consult my own

wishes, the number of guests would soon be reduced by one.

He appeared to be a very

choleric old person. "Sir," said he, "you seem disposed to

carry things off with a high hand; but I suspect that you know

more than you choose to reveal. Be so good as to tell me the

name of the lady who is staying here.

"I think you are forgetting

yourself," I answered with dignity. "I must decline to gratify

your curiosity.

He stuck his arms akimbo, and

planted himself directly in front of me, frowning ominously.

"Let us waste no more words," he said. "If I have made a

mistake, I shall be ready to offer you a full apology. If

not--But that is nothing to the purpose. I am

Lieutenant-General Graf von Rosenau, at your service, and I have

reason to believe that my son, Graf Albrecht von Rosenau, a

lieutenant in his Imperial and Royal Majesty's 99th Croat

Regiment, has made a runaway match with a certain Signorina

Bianca Marinelli of Venice. Are you prepared to give me your

word of honour as a gentleman and an Englishman that you are not

privy to this affair?"

At these terrible words I felt

my blood run cold. I may have lost my presence of mind; but I

don't know how I could have got out of the dilemma even if I had

preserved it.

"Your son has not yet arrived,"

I stammered.

He pounced upon me like a cat

upon a mouse, and gripped both my arms above the elbow. "Is he

married?" he hissed, with his red nose a couple of inches from

mine.

"No," I answered, "he is not.

Perhaps I had better say at once that if you use personal

violence I shall defend myself, in spite of your age.

Upon this he was kind enough to

relax his hold.

"And pray, sir," he resumed, in

a somewhat more temperate tone, after a short period of

reflection, "what have you to do with all this?"

"I am not bound to answer your

questions, Herr Graf," I replied; "but, as things have turned

out, I have no special objection to doing so. Out of pure

good-nature to your son, who was detained by duty in Venice at

the last moment, I consented to bring the Signorina Marinelli

here yesterday, and to await his arrival, which I am now

expecting.

"So you ran away with the girl,

instead of Albrecht, did you? Ho, ho, ho!"

I had seldom heard a more

grating or disagreeable laugh.

"I did nothing of the sort," I

answered, tartly. "I simply undertook to see her safely through

the first stage of her journey.

"And you will have the pleasure

of seeing her back, I imagine; for as for my rascal of a boy, I

mean to take him off home with me as soon as he arrives; and I

can assure you that I have no intention of providing myself with

a daughter-in-law in the course of the day.

I began to feel not a little

alarmed. "You cannot have the brutality to leave me here with a

young woman whom I am scarcely so much as acquainted with on my

hands!" I cried, half involuntarily. "What in the world should

I do?"

The old gentleman gave vent to a

malevolent chuckle. "Upon my word, sir," said he, "I can only

see one course open to you as a man of honour. You must marry

her yourself.

At this I fairly lost all

patience, and gave the Graf my opinion of his conduct in terms

the plainness of which left nothing to be desired. I included

him, his son, and the entire German people in one sweeping

anathema. No Englishman, I said, would have been capable of

either insulting an innocent lady, or of so basely leaving in

the lurch one whose only fault had been a too great readiness to

sacrifice his own convenience to the interests of others. My

indignation lent me a flow of words such as I should never have

been able to command in calmer moments; and I dare say I should

have continued in the same strain for an indefinite time, had I

not been summarily cut short by the entrance of a third person.

There was no occasion for this

last intruder to announce himself, in a voice of thunder, as the

Marchese Marinelli. I had at once recognised the original of

the signorina's photograph, and I perceived that I was now in

about as uncomfortable a position as my bitterest enemy could

have desired for me. The German old gentleman had been very

angry at the outset; but his wrath, as compared with that of the

Italian, was as a breeze to a hurricane. The marchese was

literally quivering from head to foot with concentrated fury.

His face was deadly white, his strongly marked features twitched

convulsively, his eyes blazed like those of a wild animal.

Having stated his identity in the manner already referred to, he

made two strides toward the table by which I was seated, and

stood glaring at me as though he would have sprung at my

throat. I thought it might avert consequences which we should

both afterward deplore if I were to place the table between us;

and I did so without loss of time. From the other side of that

barrier I adjured my visitor to keep cool, pledging him my word,

in the same breath, that there was no harm done as yet.

"No harm!" he repeated, in a

strident shout that echoed through the bare room. "Dog!

Villain! You ensnare my daughter's affections--you entice her

away from her father's house--you cover my family with eternal

disgrace--and then you dare to tell me there is no harm done!

Wait a little, and you shall see that there will be harm enough

for you. Marry her you must, since you have ruined her; but you

shall die for it the next day! It is I--I, Ludovico

Marinelli--who swear it!"

I am aware that I do but scant

justice to the marchese's inimitable style. The above sentences

must be imagined as hurled forth in a series of yells, with a

pant between each of them. As a melodramatic actor this

terrific Marinelli would, I am sure, have risen to the first

rank in his profession.

"Signore," I said, "you are

under a misapprehension. I have ensnared nobody's affections,

and I am entirely guiltless of all the crimes which you are

pleased to attribute to me.

"What? Are you not, then, the

hound who bears the vile and dishonoured name of Von Rosenau?"

"I am not. I bear the less

distinguished, but, I hope, equally respectable patronymic of

Jenkinson.

But my modest disclaimer passed

unheeded, for now another combatant had thrown himself into the

fray.

"Vile and dishonoured name! No

one shall permit himself such language in my presence. I am

Lieutenant-General Graf von Rosenau, sir, and you shall answer

to me for your words.

The Herr Graf's knowledge of

Italian was somewhat limited; but, such as it was, it had

enabled him to catch the sense of the stigma cast upon his

family, and now he was upon his feet, red and gobbling, like a

turkey-cock, and prepared to do battle with a hundred irate

Venetians if need were.

The marchese stared at him in

blank amazement. "You!" he ejaculated--"you Von Rosenau!

It is incredible--preposterous. Why, you are old enough to be

her grandfather.

"Not old enough to be in my

dotage,--as I should be if I permitted my son to marry a

beggarly Italian,--nor too old to punish impertinence as it

deserves," retorted the Graf.

"Your son? You are the father

then? It is all the same to me. I will fight you both. But

the marriage shall take place first.

"It shall not.

"It shall.

"Insolent slave of an Italian, I

will make you eat your words!"

"Triple brute of a German, I

spit upon you!"

"Silence, sir!"

"Silence yourself!"

During this animated dialogue I

sat apart, softly rubbing my hands. What a happy dispensation

it would be, I could not help thinking, if these two old madmen

were to exterminate each other, like the Kilkenny cats! Anyhow,

their attention was effectually diverted from my humble person,

and that was something to be thankful for.

Never before had I been

privileged to listen to so rich a vocabulary of vituperation.

Each disputant had expressed himself, after the first few words,

in his own language, and between them they were now making

hubbub enough to bring the old house down about their ears. Up

came the padrona to see the fun; up came her fat husband, in his

shirt-sleeves and slippers; and her long-legged sons, and her

tousle-headed daughters, and the maid-servant, and the cook, and

the ostler--the whole establishment, in fact, collected at the

open folding-doors, and watched with delight the progress of

this battle of words. Last of all, a poor little trembling

figure, with pale face and eyes big with fright, crept in, and

stood, hand on heart, a little in advance of the group. I

slipped to her side, and offered her a chair, but she neither

answered me nor noticed my presence. She was staring at her

father as a bird stares at a snake, and seemed unable to realise

anything except the terrible fact that he had followed and found

her.

Presently the old man wheeled

round, and became aware of his daughter.

"Unhappy girl!" he exclaimed,

"what is this that you have done?"

I greatly fear that the

marchese's paternal corrections must have sometimes taken a more

practical shape than mere verbal upbraidings; for poor Bianca

shrank back, throwing up one arm, as if to shield her face, and,

with a wild cry of "Alberto! Come to me!" fell into the arms of

that tardy lover, who at that appropriate moment had made his

appearance, unobserved, upon the scene.

The polyglot disturbance that

ensued baffles all description. Indeed, I should be puzzled to

say exactly what took place, or after how many commands,

defiances, threats, protestations, insults, and explanations, a

semblance of peace was finally restored. I only know that, at

the expiration of a certain time, three of us were sitting by

the open window, in a softened and subdued frame of mind,

considerately turning our backs upon the other two, who were

bidding each other farewell at the farther end of the room.

It was the faithless Johann, as

I gathered, who was responsible for this catastrophe. His

heart, it appeared, had failed him when he had discovered that

nothing less than a bona-fide marriage was to be the outcome of

the meetings he had shown so much skill in contriving, and, full

of penitence and alarm, he had written to his old master,

divulging the whole project. It so happened that a recent storm

in the mountains had interrupted telegraphic communication, for

the time, between Austria and Venice, and the only course that

had seemed open to Herr von Rosenau was to start post-haste for

the latter place, where, indeed, he would have arrived a day too

late had not Albrecht's colonel seen fit to postpone his leave.

In this latter circumstance also the hand of Johann seemed

discernible. As for the marchese, I suppose he must have

returned rather sooner than had been expected from Padua, and

finding his daughter gone, must have extorted the truth from his

housekeeper. He did not volunteer any explanation of his

presence, nor were any of us bold enough to question him.

As I have said before, I have no

very clear recollection of how an understanding was arrived at

and bloodshed averted and the padrona and her satellites hustled

downstairs again. Perhaps I may have had some share in the work

of pacification. Be that as it may, when once the exasperated

parents had discovered that they both really wanted the same

thing,--namely, to recover possession of their respective

offspring, to go home, and never meet each other again,--a

species of truce was soon agreed upon between them for the

purpose of separating the two lovers, who all this time were

locked in each other's arms, in the prettiest attitude in the

world, vowing loudly that nothing should ever part them.

How often since the world began

have such vows been made and broken--broken, not willingly, but

of necessity--broken and mourned over, and, in due course of

time, forgotten! I looked at the Marchese di San Silvestro the

other night, as she sailed up the room in her lace and diamonds,

with her fat little husband toddling after her, and wondered

whether, in these days of her magnificence, she ever gave a

thought to her lost Alberto--Alberto, who has been married

himself this many a long day, and has succeeded to his father's

estates, and has numerous family, I am told. At all events, she

was unhappy enough over parting with him at the time. The two

old gentlemen, who, as holders of the purse-strings, knew that

they were completely masters of the situation, and could afford

to be generous, showed some kindliness of feeing at the last.

They allowed the poor lovers an uninterrupted half-hour in which

to bid each other adieu forever, and abstained from any needless

harshness in making their decision known. When the time was up,

two travelling-carriages were seen waiting at the door. Count

von Rosenau pushed his son before him into the first; the

marchese assisted the half-fainting Bianca into the second; the

vetturini cracked their whips, and presently both vehicles were

rolling away, the one toward the north, the other toward the

south. I suppose the young people had been promising to remain

faithful to each other until some happier future time should

permit of their union, for at the last moment Albrecht thrust

his head out of the carriage window, and, waving his hand,

cried, "A rivederci!" I don't know whether they ever met

again.

The whole scene, I confess, had

affected me a good deal, in spite of some of the absurdities by

which it had been marked; and it was not until I had been alone

for some time, and silence had once more fallen upon the

Longarone osteria, that I awoke to the fact that it was

my carriage which the Marchese Marinelli had calmly

appropriated to his own use, and that there was no visible means

of my getting back to Venice that day. Great was my anger and

great my dismay when the ostler announced this news to me, with

a broad grin, in reply to my order to put the horses to without

delay.

"But the marchese himself--how

did he get here?" I inquired.

"Oh, he came by the diligence.

"And the count--the young

gentleman?"

"On horseback, signore; but you

cannot have his horse. The poor beast is half dead as it is.

"Then will you tell me how I am

to escape from your infernal town? For nothing shall induce me

to pass another night here.

"Eh! There is the diligence

which goes through at two o'clock in the morning!"

There was no help for it. I sat

up for that diligence, and returned by it to Mestre, seated

between a Capuchin monk and a peasant farmer whose whole system

appeared to be saturated with garlic. I could scarcely have

fared worse in my bed at Longarone.

And so that was my reward for

an act of disinterested kindness. It is only experience that

can teach a man to appreciate the ingrained thanklessness of the

human race. I was obliged to make a clean breast of it to my

sister, who of course did not keep the secret long; and for some

time afterward I had to submit to a good deal of mild chaff upon

the subject from my friends. But it is an old story now, and

two of the actors in it are dead, and of the remaining three I

dare say I am the only one who cares to recall it. Even to me

it is a somewhat painful reminiscence. The End (From Stories by English Authors: Italy, available via

Gutenberg Project,

either to read online or to download for free. A visit to the

Gutenberg Project catalog

is a revelation for any book lover. Be prepared to set aside a lot

of time to browse the books.)

The Grand Tour, Roman Paintings, Post-Card Art

![]()

The Grand Tour

![]()

BIANCA

By W. E. Norris