Candida Martinelli's Italophile Site

Main

Page This family-friendly site celebrates Italian culture for the enjoyment of children and

adults. Site-Overview

An

account of an Italian immigrant to America, related in the book Twilight

in Italy, by D. H. Lawrence, 1916

(ed.: The account begins with the meeting in an Italian village of

Giovanni’s father, mother, wife and baby in a small café.

Then Mr. Lawrence and his friends meet the son, Giovanni, of whom

his father has spoken so highly, and boasted of Giovanni's ability to

speak English.)

Soon

Giovanni came home, and took his cornet upstairs. Then he came to see us.

He was an ingenuous youth, sordidly shabby and dirty.

His fair hair was long and uneven, his very high starched collar

made one aware that his neck and his ears were not clean, his American

crimson tie was ugly, his clothes looked as if they had been kicking

about on the floor for a year.

Yet

his blue eyes were warm and his manner and speech very gentle.

'You

will speak English with us,' I said.

'Oh,'

he said, smiling and shaking his head, 'I could speak English very well.

But it is two years that I don't speak it now, over two years

now, so I don't speak it.'

'But

you speak it very well.'

'No.

It is two years that I have not spoke, not a word--so, you see, I

have--'

'You

have forgotten it? No, you haven't.

It will quickly come back.'

'If

I hear it--when I go to America--then I shall--I shall--'

'You

will soon pick it up.'

'Yes--I

shall pick it up.'

The

landlord, who had been watching with pride, now went away.

The wife also went away, and we were left with the shy, gentle,

dirty, and frowsily-dressed Giovanni.

He

laughed in his sensitive, quick fashion.

'The

women in America, when they came into the store, they said, "Where

is John, where is John?" Yes, they liked me.'

And

he laughed again, glancing with vague, warm blue eyes, very shy, very

coiled upon himself with sensitiveness.

He

had managed a store in America, in a smallish town. I glanced at his reddish, smooth, rather knuckly hands, and

thin wrists in the frayed cuff. They

were real shopman's hands.

The

landlord brought some special feast-day cake, so overjoyed he was to

have his Giovanni speaking English with the Signoria.

When

we went away, we asked 'John' to come down to our villa to see us.

We scarcely expected him to turn up.

Yet

one morning he appeared, at about half past nine, just as we were

finishing breakfast. It was

sunny and warm and beautiful, so we asked him please to come with us

picnicking.

He

was a queer shoot, again, in his unkempt longish hair and slovenly

clothes, a sort of very vulgar down-at-heel American in appearance.

And he was transported with shyness.

Yet ours was the world he had chosen as his own, so he took his

place bravely and simply, a hanger-on.

We

climbed up the water-course in the mountain-side, up to a smooth little

lawn under the olive trees, where daisies were flowering and gladioli

were in bud. It was a tiny

little lawn of grass in a level crevice, and sitting there we had the

world below us--the lake, the distant island, the far-off low Verona

shore.

Then

'John' began to talk, and he talked continuously, like a foreigner, not

saying the things he would have said in Italian, but following the

suggestion and scope of his limited English.

In

the first place, he loved his father--it was 'my father, my father'

always. His father had a

little shop as well as the inn in the village above.

So John had had some education. He had been sent to Brescia and then to Verona to school, and

there had taken his examinations to become a civil engineer.

He was clever, and could pass his examinations.

But he never finished his course.

His mother died, and his father, disconsolate, had wanted him at

home. Then he had gone

back, when he was sixteen or seventeen, to the village beyond the lake,

to be with his father and to look after the shop.

'But

didn't you mind giving up all your work?' I said.

He

did not quite understand.

'My

father wanted me to come back,' he said.

It

was evident that Giovanni had had no definite conception of what he was

doing or what he wanted to do. His

father, wishing to make a gentleman of him, had sent him to school in

Verona. By accident he had

been moved on into the engineering course.

When it all fizzled to an end, and he returned half-baked to the

remote, desolate village of the mountain-side, he was not disappointed

or chagrined. He had never conceived of a coherent purposive life.

Either one stayed in the village, like a lodged stone, or one

made random excursions into the world, across the world.

It was all aimless and purposeless.

So

he had stayed a while with his father, then he had gone, just as

aimlessly, with a party of men who were emigrating to America. He had taken some money, had drifted about, living in the

most comfortless, wretched fashion, then he had found a place somewhere

in Pennsylvania, in a dry goods store.

This was when he was seventeen or eighteen years old.

All

this seemed to have happened to him without his being very much

affected, at least consciously. His

nature was simple and self-complete.

Yet not so self-complete as that of Il Duro or Paolo.

They had passed through the foreign world and been quite

untouched. Their souls were

static, it was the world that had flowed unstable by.

But

John was more sensitive, he had come more into contact with his new

surroundings. He had

attended night classes almost every evening, and had been taught English

like a child. He had loved

the American free school, the teachers, the work.

But

he had suffered very much in America.

With his curious, over-sensitive, wincing laugh, he told us how

the boys had followed him and jeered at him, calling after him, 'You

damn Dago, you damn Dago.' They had stopped him and his friend in the

street and taken away their hats, and spat into them.

So that at last he had gone mad.

They were youths and men who always tortured him, using bad

language which startled us very much as he repeated it, there on the

little lawn under the olive trees, above the perfect lake: English

obscenities and abuse so coarse and startling that we bit our lips,

shocked almost into laughter, whilst John, simple and natural, and

somehow, for all his long hair and dirty appearance, flower-like in

soul, repeated to us these things which may never be repeated in decent

company.

'Oh,'

he said, 'at last, I get mad. When

they come one day, shouting, "You damn Dago, dirty dog," and

will take my hat again, oh, I get mad, and I would kill them, I would

kill them, I am so mad. I

run to them, and throw one to the floor, and I tread on him while I go

upon another, the biggest. Though

they hit me and kick me all over, I feel nothing, I am mad.

I throw the biggest to the floor, a man; he is older than I am,

and I hit him so hard I would kill him.

When the others see it they are afraid, they throw stones and hit

me on the face. But I don't

feel it--I don't know nothing. I

hit the man on the floor, I almost kill him.

I forget everything except I will kill him--'

'But

you didn't?'

'No--I

don't know--' and he laughed his queer, shaken laugh. 'The other man that was with me, my friend, he came to me and

we went away. Oh, I was

mad. I was completely mad.

I would have killed them.'

He

was trembling slightly, and his eyes were dilated with a strange greyish-blue

fire that was very painful and elemental.

He looked beside himself. But

he was by no means mad.

We

were shaken by the vivid, lambent excitement of the youth, we wished him

to forget. We were shocked,

too, in our souls to see the pure elemental flame shaken out of his

gentle, sensitive nature. By

his slight, crinkled laugh we could see how much he had suffered.

He had gone out and faced the world, and he had kept his place,

stranger and Dago though he was.

'They

never came after me no more, not all the while I was there.'

Then

he said he became the foreman in the store--at first he was only

assistant. It was the best

store in the town, and many English ladies came, and some Germans. He liked the English ladies very much: they always wanted him

to be in the store. He wore

white clothes there, and they would say:

'You

look very nice in the white coat, John'; or else:

'Let

John come, he can find it'; or else they said:

'John

speaks like a born American.'

This

pleased him very much.

In

the end, he said, he earned a hundred dollars a month.

He lived with the extraordinary frugality of the Italians, and

had quite a lot of money.

He

was not like Il Duro. Faustino

had lived in a state of miserliness almost in America, but then he had

had his debauches of shows and wine and carousals.

John went chiefly to the schools, in one of which he was even

asked to teach Italian. His

knowledge of his own language was remarkable and most unusual!

'But

what,' I asked, 'brought you back?'

'It

was my father. You see, if

I did not come to have my military service, I must stay till I am forty.

So I think perhaps my father will be dead, I shall never see him.

So I came.'

He

had come home when he was twenty to fulfill his military duties.

At home he had married. He

was very fond of his wife, but he had no conception of love in the old

sense. His wife was like

the past, to which he was wedded. Out

of her he begot his child, as out of the past.

But the future was all beyond her, apart from her.

He was going away again, now, to America.

He had been some nine months at home after his military service

was over. He had no more to

do. Now he was leaving his

wife and child and his father to go to America.

'But

why,' I said, 'why? You are not poor, you can manage the shop in your

village.'

'Yes,'

he said. 'But I will go to

America. Perhaps I shall go

into the store again, the same.'

'But

is it not just the same as managing the shop at home?'

'No--no--it

is quite different.'

Then

he told us how he bought goods in Brescia and in Said for the shop at

home, how he had rigged up a funicular with the assistance of the

village, an overhead wire by which you could haul the goods up the face

of the cliffs right high up, to within a mile of the village.

He was very proud of this. And

sometimes he himself went down the funicular to the water's edge, to the

boat, when he was in a hurry. This

also pleased him.

But

he was going to Brescia this day to see about going again to America.

Perhaps in another month he would be gone.

It

was a great puzzle to me why he would go.

He could not say himself. He

would stay four or five years, then he would come home again to see his

father--and his wife and child.

There

was a strange, almost frightening destiny upon him, which seemed to take

him away, always away from home, from the past, to that great, raw

America. He seemed scarcely

like a person with individual choice, more like a creature under the

influence of fate which was disintegrating the old life and

precipitating him, a fragment inconclusive, into the new chaos.

He

submitted to it all with a perfect unquestioning simplicity, never even

knowing that he suffered, that he must suffer disintegration from the

old life. He was moved

entirely from within, he never questioned his inevitable impulse.

'They

say to me, "Don't go--don't go"--' he shook his head.

'But I say I will go.'

And

at that it was finished.

So

we saw him off at the little quay, going down the lake.

He would return at evening, and be pulled up in his funicular

basket. And in a month's

time he would be standing on the same lake steamer going to America.

Nothing

was more painful than to see him standing there in his degraded, sordid

American clothes, on the deck of the steamer, waving us good-bye,

belonging in his final desire to our world, the world of consciousness

and deliberate action. With

his candid, open, unquestioning face, he seemed like a prisoner being

conveyed from one form of life to another, or like a soul in trajectory,

that has not yet found a resting-place.

What

were wife and child to him?--they were the last steps of the past.

His father was the continent behind him; his wife and child the

foreshore of the past; but his face was set outwards, away from it

all--whither, neither he nor anybody knew, but he called it America. My list of books by and about D. H. Lawrence

Also see my pages: John, Italian

Emigrant, by D. H. Lawrence Joe

Petrosino, NYC Pioneer Policeman Rivesville, West Virginia, R.T.

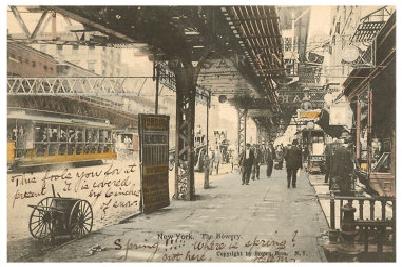

JOHN

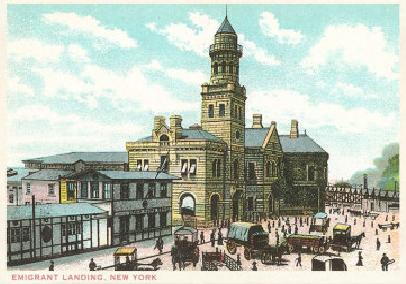

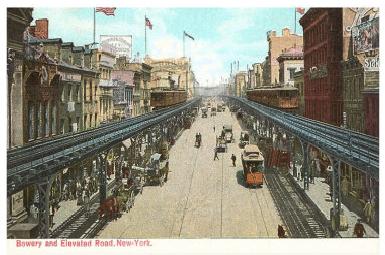

![]()

![]()

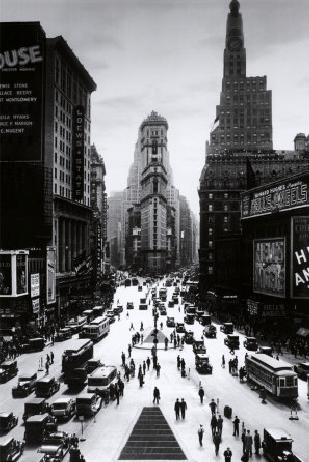

Lunch Atop a Skyscraper, 1932