Candida Martinelli's Italophile Site

Main

Page This family-friendly site celebrates Italian culture for the enjoyment of children and

adults. Site-Overview

Villa Medicee II Villa dell'Ambrogiana Villa del Trebbio Villa Cafaggiolo Villa di Castello Villa La Petraia Villa Medicee I Some images from Castle Chenonceau in France, Caterina

de' Medici's favorite castle, from where she ruled France for most of

her reign. This is the impressive tree-lined walkway leading to

the Castle that sits on the banks of the Cher River in the Loire Valley.

The Castle is actually the construction between the

tower on the right, and the walkway/corridor built across the River Cher

on the left.

These gardens are the Diane de Poitiers

Gardens.

When Caterina de' Medici took the Castle from Diane de

Poitiers, she had it remodeled putting a definite de' Medici and Italian

stamp on it. The Medici balls and Florentine crest now decorate

the ceiling of the bedroom of her former rival. An Italian garden

was added. Italian majolica and terracotta tiles decorate the

floors, the terracotta tiles stamped with the Florentine symbol. One of the changes was this staircase she had built of

Italian design, that was the first staircase in France of a style that

wasn't round. It is elaborately decorated and well-lit by a window

and balcony that looks onto the River Cher. It goes up the 3

stories of the Castle, but not down into the kitchens.

Another improvement was the conversion of a walkway

across the River Cher into a corridor used for state functions and

parties, as seen here from a castle window.

And here, from inside.

The kitchens were in the basement and they have been

wonderfully preserved as you can see here in these images. The butcher's block with knives and the drawer in the

bottom for blood and bits that were used for sausages. The hooks

are for hanging fowl and other meats.

Another butcher's block, well-used, with the handy

drawer underneath.

One of the hearths with cooking pots hanging, and the

table full of produce.

The bread oven with bread forms and a ready supply of

wood.

If you step back, you can see the bread paddles, the

same type that are used by pizza makers around the world.

Here you can see that the bread oven sit next to a

cooking hearth.

The sink with a pump that pumps water from the River

Cher below.

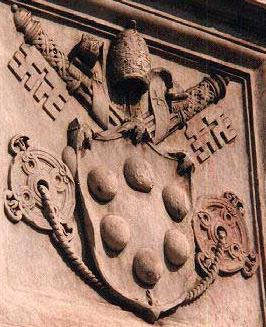

Giulio de' Medici (1478-1534) was his cousin's advisor all through his

papacy as Leo X, so he understood the situation of the church and the politics

when he was elected to the position, after the death after only two years as

Pope, of Adrian VI, in 1523.

Giulio took the name Pope Clement VII.

He reluctantly made12-year-old Ippolito the nominal head

of the de' Medici family interests in Florence, over his own

illegitimate son Alessandro. As Giulio was illegitimate too, his illegitimate son

had less claim on the title. Giulio made Alessandro

the Duke of the Italian city Penne, in compensation.

All Giulio's experience didn't mean he was a particularly skilled Pope

from our point of view. But from his point of view, there wasn't

much he could do but try to walk a tightrope between the two other

great European powers of the time: Giulio also tried to straddle the fence on the

Lutheran problem.

He and the other Cardinals had opposed Pope Adrian VI's attempts to

reform the Catholic Church from within to counter the Lutheran

points. The Cardinals continued this opposition under Pope Clement VII.

So when Henry the VIII of

Britain wanted a divorce, they stuck to the letter of the current law

and denied it, being especially angered by his betrothed's sympathies

with the Lutherans. This denied divorce resulted famously in the

schism that established the Church of England. Giulio, as Pope Clement VII, didn't neglect his

artistic duties

to his family. He had Michelangelo design and create a building

worthy of the de' Medici library, a collection begun by Cosimo the Elder. The

beautiful Laurentian Library still stands today in Florence and is open to the public.

Charles V sacked Rome in 1527 when the mercenaries under

Giovanni delle Bande Nere, a de' Medici from the junior branch, was defeated.

Giovanni died defending Rome. During the resulting sack of Rome, thousands were murdered and tortured, and the Vatican

was looted of it's art and books.

Pope Clement VII was held prisoner in Castel Sant'Angelo until the Pope bribed

some guards

and managed to escape to Tuscany dressed as a peddler.

This print ridicules the

situation which does suggest something of the surreal about it.

Filippo Strozzi happened to be with the Pope at the time, and the Pope

turned him over to the enemy in the hopes of gaining his own release. Strozzi was shipped off to prison in Naples.

This was yet another reason for

the Strozzi to dislike the de' Medici, as if they needed one.

Castel Sant'Angelo, Rome

During all the confusion, the republican element in Florence reasserted

itself and re-established the Florentine Republic.

Alessandro and Ippolito fled

with their protector, the Cardinal of Florence, but they

left behind their 8 year-old cousin Caterina.

The republican forces took possession of all

the de' Medici property, again, and they took Caterina de' Medici captive,

keeping her locked up in a convent.

Florence was immediately hit

by an epidemic that killed thousands of people. The Republic lasted only 3 years this

time. Pope Clement VII signed a truce with Charles V and together they

laid

siege to Florence.

Michelangelo, who was in Florence during

this time working on the de' Medici crypt and library, joined the

republican forces and supervised defenses that helped keep out the

advancing armies. His defensive earthworks meant that the city was

not overrun, but put under siege, a siege that lasted nearly a year.

Pope Clement VII demanded the safe release of his

grand-niece Caterina. But the republicans were undecided whether

to either place the child on the city walls exposed to the de' Medici

artillery bombardments, or give her to the soldiers to dishonor. Tough

choice! What a lovely era!

Catherine de' Medici as a child

Eventually,

after a deal was brokered between the Pope and Charles V, the Pope's

forces retook the city in 1530 and Caterina was brought to Rome.

Clement VII ordered that Michelangelo, a childhood

friend, be

spared death and be allowed instead to return to work on the family

tombs and library. But Michelangelo knew that he'd made an enemy

of the younger de' Medici, and the failure of the Florentine Republic

hurt him deeply.

Clement VII and Charles V's deal:

Alessandro took little Caterina into his care as new head of the de' Medici

family. Alessandro's nickname 'Il Moro' means 'the Moor', and was given to

Alessandro because of his dark skin

from his North African mother. She was a serving girl in a de' Medici

Palace when she conceived Alessandro with then Cardinal Giulio.

There are competing theories that she was either a black-African or of mixed

parentage. But from this portrait by the rather honest Pontormo,

Alessandro looks very North African.

Alessandro de' Medici by Pontormo

A bit later on, Clement VII managed to get Charles V to sell a

Dukedom to Alessandro making him the first Duke of the

new Duchy of Florence in 1532. Clement VII hoped the title and

protection of the Holy Roman Emperor would make Alessandro appear more

legitimate to the Florentines.

This was a huge miscalculation.

The Florentines still harbored hopes of regaining their Republic, and

the annexation of Florence by Charles V, angered many republicans,

including members of the junior branch of the de' Medici family.

Duke of Florence Alessandro by Vasari

A part of the deal, Charles V offered to Alessandro in marriage

Charles's illegitimate daughter,

Margaret, then 9 years old. Alessandro married her

in 1533 but kept the woman he loved as his

mistress. His only children to live to adulthood were fathered with her

and were named Giulio and Giulia

de' Medici, after his father.

Alessandro's father, Pope Clement VII, hired Michelangelo, to paint the

Last

Judgment on a wall of the Sistine Chapel, but the Pope didn't live to see it

completed. Clement VII served as Pope until 1534, when he died from

eating a poisonous mushroom. That's not really as suspicious as it

sounds in a time when there was little industrial mushroom production,

and the Pope was a famous glutton.

Pope Clement VII was Michelangelo's protector against

Alessandro, who hated the artist for his republican beliefs. So

when Pope Clement VII died in 1534, Michelangelo decided to remain in

Rome rather than return to his beloved Florence. Michelangelo was

54, and he was to live to be nearly 100 in Rome, never returning to

Florence until after his death, brought there by another de' Medici for

burial and royal honors, but more about that in the next section.

And what of little Caterina at this time? Caterina's great-uncle, Pope Clement VII,

married her

off in 1533 at the age of 14, with Alessandro's approval and

assistance, to the second son of

Francois I the King of France, Henry the Duke of Orleans, who was also 14.

This was a strategic move by the Pope, trying to keep

a foot in both camps: the French House of Valois, and

the Holy Roman Emperor with Caterina's marriage, and through Alessandro's link to

Charles V through his marriage.

For Caterina, in the long run,

it was probably for the best. Her mother was of the House of Tour de Boulogne

and was closely linked to the French royal families. Her

mother also left

Caterina

great personal wealth.

And Caterina was actually:

Early on, Caterina had a low position in the rich French court,

and her position was even more precarious after the death of her uncle, the Pope,

in 1534.

But when the King's first son, the Duke of Albany, died of poisoning,

(other reports say he died of a chill after tennis) Caterina's husband

became the next in line for the French crown, the Dauphin, and

Caterina's stature rose as well.

The death of the Duke of Albany

is very suspicious especially since: Well, when

the de' Medici are involved, and they really, really wanted Caterina to

be French Queen, anything is conceivable.

So many conceived the assassination possible, that the man was arrested,

tortured and tried. But he never confessed to working for the de'

Medici. It served the

French King, Francois I, to implicate his enemy Charles V, and when the

prisoner helpfully confessed to this, he was killed.

Years later, Caterina

would kill an enemy in much the same way the Duke of Albany was killed,

with perhaps the same poison. One of the more popular, if gruesome,

exhibits in France is Caterina de' Medici's poison cabinet at Versailles.

I have more about Caterina below on this same page. Her life was

long and interesting, to say the least.

After his father, Pope Clement, died, Alessandro felt less

secure of his position. In response to his insecurity and a

weak nature, he took more and more power

into his own hands. And as it's known to do, the absolute power corrupted him absolutely.

Alessandro tried

to secure his position by having his cousin Ippolito, now

Cardinal de' Medici, poisoned,

in 1535. Although Ippolito officially died of malaria, en route to Charles V to complain about Alessandro's rule of

Florence, few doubt Alessandro had a hand in assassinating his cousin.

Ippolito was only 24 years old, and was widely respected

for his regal bearing and intelligence.

Ippolito de' Medici, he just missed out an

being head of the family, and by all accounts he would have been a

worthy one

Alessandro began to indulge all his illicit desires, leaving himself vulnerable to hangers-on

and courtiers who supplied him with whatever he desired.

Alessandro's cousin Lorenzino became one of those courtiers, but with ulterior motives.

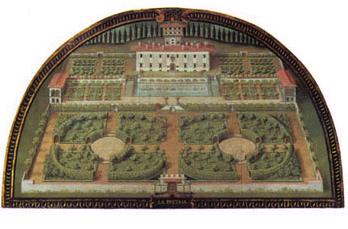

One of Alessandro's whims, was to take possession of the

Villa della Petraia, which wasn't much of a villa at all at the time. It

was a medieval fortress and farming estate. Alessandro died before

he could do much with it. It's rebuilding was taken on by a later

de' Medici.

All this bad feeling gave the junior side of the de'

Medici family an opportunity. They saw that they had a good

chance to finally

take control of the family empire.

Lorenzo de' Medici,

the father of the junior line of de' Medici, had a great-grandson, Lorenzino

(1514-1548), the same Lorenzino who had befriended Alessandro.

Lorenzino used his courtier status and false friendship to lure Alessandro

undefended to his death.

Lorenzino had his assassins stab Alessandro to death in 1537,

as Alessandro arrived for an assignation with his beautiful cousin, Lorenzino's sister.

Alessandro, born in

1510, died at the very young age of 27, and was buried in his uncle's

tomb, Lorenzo the Duke of Urbino, in the New Sacristy made by

Michelangelo.

The reason he was buried in his uncle's tomb was

because the de' Medici family had always put forth the lie that

Alessandro was the Duke of Urbino's illegitimate child. This was

meant to save Cardinal Giulio the shame of fathering a

child while a Cardinal.

Lorenzino escaped to Venice and wrote an account of the killing

called Apologia (Apology), which he had published and sold throughout Europe.

In his Apology, he said he killed his cousin to give the

Florentine Republic a chance to return to power.

Perhaps this is

true, perhaps not. Coming from a de' Medici, especially one from

the devious junior branch of the family, many dismissed this claim. The claim was beside the point, because the republican revolt never happened. Lorenzino had killed the last viable de'

Medici from the senior line, leaving himself, at age 23, the next in line to take

over the family interests, so no one believed his Apology.

Granted, history is written by the victors, but Lorenzino's assassination of his own

cousin, head of the de' Medici family, caused in his own lifetime for his nickname to become Lorenzaccio, the Bad Lorenzo.

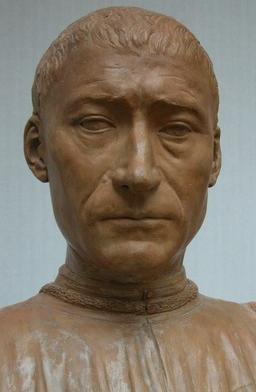

He had another nickname given by many people, Brutus Lorenzino, and this bust of Brutus,

one of the men who betrayed Caesar and killed him, is by Michelangelo from

1540. It's said Michelangelo was inspired by Lorenzaccio when he

crafted the expression of contempt and arrogance.

Just so you know: Not everyone condemned Lorenzino. Filippo

Strozzi, a longtime business rival of the de' Medici, and supporter of a

republican Florence, ordered his sons to marry the daughters of Lorenzino to ensure his grandchildren would inherit his cunning,

determination and courage for the sake of liberty.

Filippo Strozzi

Strozzi's sons did as their father wished. Oddly enough, they lived in France at that

time, attached to the court of Caterina de' Medici, who was their cousin by

marriage, even before they married into the junior branch of the de'

Medici family.

Many years back, Filippo Strozzi had married Caterina de' Medici's aunt in a

bid by the de' Medici to buy him off. It didn't work, but Strozzi

loved his wife, Clarissa, deeply.

Strozzi's beloved wife Clarissa de' Medici, Caterina

de' Medici's aunt, in a classic pose signifying love, supposedly love

for Filippo Strozzi

On Clarissa's death, Strozzi returned to Florence,

renewed ties with the de' Medici family, and eventually became

head of Caterina de' Medici's household when she went to France to marry Henry de

Valois.

Strozzi returned to Florence after the death of Pope Clement

VII, and possibly helped orchestrate the death of Alessandro.

Filippo Strozzi was among the group who put the de' Medici back in charge of

Florence after Alessandro's death, with the hopes that the de' Medici

from the junior branch of the family would live up to their republican

talk.

And Caterina de' Medici? She became Queen of

France in 1547 and eventually bore

Henri II 10 children in 10 years, despite his continuing affair with his mistress

Diane de Poitiers (and others), and his early inability to father children

(for which she was blamed and threatened with divorce).

It's been suggested that his repeated impregnation of a wife he didn't

want, was a plot by Henry II to kill Caterina the way her own mother had

died, in childbirth. But the plot failed.

Others say the pregnancies were a plot

by Henry's mistress, Diane, to keep the young Caterina in maternity confinement for years and

years so Diane and Henry II could run the country together. This plot

succeeded.

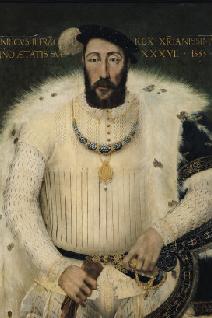

Interesting to note how times change,

Diane was ridiculed for keeping herself young and attractive

for her

much younger lover Henry II, by using false teeth and false hair and

much makeup and fancy dress. It sounds like an awful lot of work to keep this

not-so-cheery-looking fellow, if you ask me, but I'm not a power junkie.

Caterina waited patiently for a chance to gain some influence for herself and her

children. And she maintained contact with her relations in Italy, but

was careful not to have Italians in her retinue in France, to avoid any

accusations of being a traitor to France.

After Henry II's illness from injuries sustained

in a friendly joust, and his subsequent death in

1559, Caterina

banished his mistress and proceeded to skillfully take the reigns of power in

France.

She also took Castle Chenonceau from Diane, had it

redecorated for herself, then lived there off and on for years. I

include in the left column some photos I took from a recent visit to the

beautiful Castle. I highly recommend a visit if possible.

You can read more about it at

it's

Wikipedia page.

Caterina held the country together under the House of Valois during

the tumultuous:

And Caterina

spent much of her time planning the marriages of her children, all for

political gain, of course.

Caterina's third and favorite son, Alencon d'Anjou,

was offered to Queen Elizabeth of England. But Elizabeth objected to his

young age and pockmarked face from an earlier bout with small-pox, a

common condition in those days, one that Elizabeth herself had suffered

leaving similar scars.

When the English physicians

offered to treat the scars to lessen then, Caterina told them to test

the treatments on a court page first. If the page lived, and the

cure worked, they

could then use them on her son. Sweet lady!

In the end, Elizabeth rejected Alencon, scars or no

scars, as

she rejected all her suitors. This was most probably because under the terms of

her father, Henry VIII's, will, Elizabeth lost all power and all her wealth if

she married. Sounds like Henry wanted her to be the Virgin Queen

she turned out to be.

Caterina was a famous spreader of Italian

culture from cuisine, ceramics, couture and makeup, to perfumes, to the use of

secret poisons to eliminate enemies over cocktails and dump them through

trap doors in the floor.

Caterina was also, like all the de'

Medici, a patron of artists and architects, leaving grand buildings

around Paris with her and her husband's initials on them, including The Louvre Museums and the Tuileries.

Caterina died at the age of

70 in 1589, while giving political advice to her son, Henry III, on her

deathbed.

Here's a link to a biography of Caterina de' Medici, if you'd like to

read more about her.

To the next section:

The

de' Medici Dynasty

![]()

The family's history parallels

Italy's history. I've divided it into sections listed in the left

column.

This concise history is a helpful guide to read before

traveling to Florence and the Vatican.

The de' Medici Dynasty and Italian History

The Late-Middle-Ages, Early Renaissance, Giovanni: The Founder

The Early Renaissance, Cosimo and Lorenzo: The Elders

The High Renaissance, Piero and his son, Lorenzo the Magnificent

Florentine Independence and the End of the

Florentine Renaissance, Piero II and Lorenzo II in Exile

The Roman Renaissance, Cardinal Giulio de' Medici and Pope Leo X

(Giovanni de' Medici)

The End of Florentine Independence, Pope Clement VII (Giulio de' Medici), Alessandro, and

Caterina de' Medici

The Late Renaissance, The Grand Duke and Duchess of Tuscany: Cosimo de' Medici

and Eleonora di Toledo

The Age of Discovery, Francesco and Ferdinando: Two Very Different Brothers

The Age of Reason and The Enlightenment, The Decline of de' Medici Reason and Enlightened

Governance

![]()

Charles V, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The End of Florentine Independence

Pope Clement VII (Giulio de' Medici), Alessandro, and

Caterina de' Medici

![]()

Pope Clement VII (1478-1534) c.1526

![]()

Charles V, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire

Caterina de' Medici, Queen of France

![]()

Diane de Poitiers Mistress of Henri II, King of France

![]()

Portrait of Catherine de Medici, Facsimile of a 16th Century Drawing

Alessandro Il Moro, Duke of Florence

![]()

Villa della Petraia

Alessandro was not everyone's first choice for Duke of Florence.

His illegitimate birth from an illegitimate father made many uneasy.

To make things worse, his rule was increasingly despotic and he raised the taxes on the

people, always a support-loser. And Florentine republicans saw

Alessandro as a major obstruction to the

return of the Florentine Republic.

Filippo Strozzi

Caterina de' Medici

![]()

Henri II (1519-59), King of France, 1555

![]()

Miniature of Catherine de Medici