Candida Martinelli's Italophile Site

Main

Page This family-friendly site celebrates Italian culture for the enjoyment of children and

adults. Site-Overview

Saint Peter baptizing a man

Saint John

Saint Peter paying taxes

Virgin and Child

A youth

Florence's cathedral with Brunelleschi's famous dome, a view from above

In the Late-Middle-Ages, city-states grew rich from trade, especially those with access to

ports, like Venice, Genoa, Pisa (Florence).

The growing trade required bankers, accountants, interpreters,

craftsmen, salesmen, distributors…in short, a middle class.

This

growing counter-balance to the power of the evermore corrupt church

dominated the end of the Middle Ages, and pushed Italy ahead of

Europe into the Renaissance.

Dante Alighieri was right there.

He is a late Middle Ages writer that is considered the bridge

with the Renaissance. He

lived from 1265-1321.

Petrarch

wrote during this transitional period, and is considered the father of

humanism, the main philosophy of the Renaissance. And Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici was there as part

of the growing middle class. The enterprising but not well-off Giovanni di Bicci

de' Medici (1360-1429) moved from Mugello to Florence. Giovanni began

by acquiring real estate in the New Market area. That area was much

later opened up by the demolition of the medieval buildings and made

into Piazza della Republica. In this image by Dutch artist Jan Van der Straet, called Giovanni Stradoni in Italy, you can see the old Piazza with the small

shops around it. Piazza del Mercato Vecchio 1555

Giovanni

built his property business into a commercial giant, adding a

pawn-broking/banking business that he expanded with branches throughout the Northern Italian

city-states and all then all of Europe. The banking business was like today's Hawala

money-transfer system. For example: The earliest banks were

also pawn-brokers, just as today's banks in Italy are also pawn-brokers.

Items were left in the bank safes as collateral for loans small and

large for usually less than half the market value of the item. If

the loans weren't repaid in a certain amount of time, the items were

sold and the 'bank' owners made their profit. It was a way of

running a bank without charging interests, which was ruled a sin by the

Vatican. Like the Islamic banks today, and for the same reason, only fees were charged for

services. Today, people in Italy use this bank service as a

substitute for credit cards. Credit cards were introduced only

recently in Italy, and the 18-25% interest on charges not paid off

immediately, are substantial compared to the small fees charged by

pawn-brokers. In fact, the famous Parmigiano cheese is actually 'pawned'

to the banks in that region of Italy. The banks offer loans to the

producers, only if they store their valuable cheeses in bank-provided

vaults. If the loans are not repaid, the bank keeps possession of

the cheese, technically called collateral for the loans. Giovanni's money bought

him entry into the high circles of Florence, but he was never part of

the aristocracy of the city, nor did he aspire to be. Like his de'

Medici relations before him, Giovanni de' Medici supported

a popular government of the people. The people of

Florence held dear to that dream with ever increasing tenacity over

the coming years, ironically fighting the tyranny of the de' Medici

along the way.

Florence's town hall in the Palazzo Vecchio Giovanni made the family home in several connecting medieval properties

along Via Cavour in Florence, then called Via Larga.

Rendering of a via Larga

procession after the Medici built their palace, seen here to the right,

on the corner He then began purchasing most of the property along with wide street,

and rented the homes to the de' Medici employees, while retaining the orchards

and vegetable plots for his sons to develop later. Giovanni was patron

to many artists including Masaccio

who is often called the first Renaissance painter. And he

supported the artist and architect Brunelleschi. Giovanni provided most of the money for the

rebuilding of his local parish church, now the Basilica di San Lorenzo,

and gave the contract for the work to Brunelleschi.

The exterior of the church was never decorated,

but the interior was embellished over the years by many famous

Florentine artists under commission to the de' Medici family.

Interior of the Basilica of San

Lorenzo Giovanni lived to the age of 69.

He was well respected in Florence and seen as a fair and peace-loving

man. He brought prestige to the city through his powerful business

contacts and hosting important guests. Before Giovanni died, he managed to

secure the Papacy as his bank's client. He was 'God's Banker',

using a

more recent term. This was a coup because the Vatican was at that time, the largest multi-national organization in the world.

The other bankers in Florence envied the de' Medici their big client,

envy that would lead to much strife down the years. Giovanni built up a multi-national

empire of commerce, property and banking, and set an example to his sons

of artistic patronage and political moderation. That's why he's

considered the patriarch of the de' Medici empire. To the next section:

The Early Renaissance, Cosimo and Lorenzo: The Elders

Florence's cathedral with Brunelleschi's famous dome, a view from the

side

The

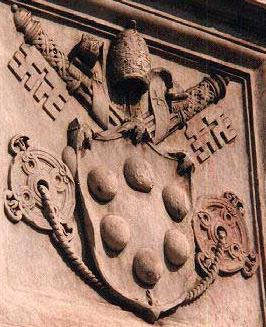

de' Medici Dynasty

![]()

The family's history parallels

Italy's history. I've divided it into sections listed in the left

column.

This concise history is a helpful guide to read before

traveling to Florence and the Vatican.

The de' Medici Dynasty and Italian History

The Late-Middle-Ages, Early Renaissance, Giovanni: The Founder

The Early Renaissance, Cosimo and Lorenzo: The Elders

The High Renaissance, Piero and his son, Lorenzo the Magnificent

Florentine Independence and the End of the

Florentine Renaissance, Piero II and Lorenzo II in Exile

The Roman Renaissance, Cardinal Giulio de' Medici and Pope Leo X

(Giovanni de' Medici)

The End of Florentine Independence, Pope Clement VII (Giulio de' Medici), Alessandro, and

Caterina de' Medici

The Late Renaissance, The Grand Duke and Duchess of Tuscany: Cosimo de' Medici

and Eleonora di Toledo

The Age of Discovery, Francesco and Ferdinando: Two Very Different Brothers

The Age of Reason and The Enlightenment, The Decline of de' Medici Reason and Enlightened

Governance

Some works by Masaccio

The Late-Middle-Ages, Early Renaissance

Giovanni: The Founder